When talking about the ongoing international race to exascale computing, it might be easy to overlook the European Union. A lot of the attention over the past several years has focused on the efforts by the United States and China, the world’s economic powerhouses and the centers of technology development.

Through its Exascale Computing Project, the United States is putting money and resources behind its plans to roll out the first of its exascale systems in 2021. For its part, China is planning at least three pre-exascale systems using mostly home-grown technologies, backed by significant investments by the Chinese government. Japan also is making a push with Fujitsu’s Post-K supercomputer that will be based on Arm’s 64-bit chip architecture and is due out toward the end of 2021.

In recent years the EU has ramped up its investments as it looks to grow its high tech industry, reduce its dependence on technologies from the United States and elsewhere, and become a top-three HPC player by 2020.

Some of that exascale effort is being driven by national pride, but much also is being fueled by the understanding that the business environment is changing with the emergence of the cloud, data analytics, smart cities and the internet of things (IoT), and that HPC technologies and eventually exascale computing will play a major role in those trends. The EU wants to take advantage of the opportunities by growing its own IT businesses, according to Francois Bodin of the European Extreme Data and Computing Initiative (EXDCI), which is charged with developing a common strategy for a European HPC ecosystem.

“We could just do nothing and we could buy everything [from vendors in other countries],” Bodin said during a session at the SC17 show in Denver this week that focused on Europe’s exascale strategy. “If we don’t do that, it’s because here are some specifics we need to cover. There are some specificities in the EU system. At the beginning of the 2000s, we had high expansion in HPC and we are losing some ground now, so we need to recover some ground we lost. If we look at why we’re building a full HPC ecosystem, this is very important for Europe and this is part of the future growth of our economy and science. The EU needs to develop more of its technology and reduce its dependence on others’ technology.”

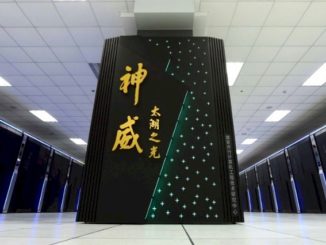

At the conference, Bodin and others involved in the EU’s HPC and exascale projects outlined the initiatives driving the region’s efforts, which range from creating a distributed supercomputing environment that spans five locations and creating Centers of Excellence to building an ecosystem that will help fuel the growth of the region’s tech industry and much-needed supply chain. Eugene Griffiths, a member of the steering board for the ETP4HPC (European Technology Platform for HPC), outlined some of the challenges the region is facing. Griffiths noted that the EU has no supercomputer listed in the top 10 of the 500 fastest supercomputers (the third fastest according to the list released this week is Piz Daint in Switzerland, which is not an EU member) and that what systems the EU has on the list are based on technology that isn’t from the EU.

He also pointed to the higher levels of funding for HPC in the United States, China and Japan, a weak supply chain that needs to grow and put more EU-based HPC technologies into the pipeline, strategy implementations that need to be less fragmented and more integrated among the EU’s 28-member states and the need for more coordinated funding. The problem becomes that EU scientists often will have to go outside of Europe to acquire the resources they need.

There are myriad initiatives underway to enable Europe to regain a foothold in the HPC space. That includes not only the Horizon 2020 program for driving R&D in the region, but also EuroHPC to lead the push to exascale, Partnership for Advanced Computing in Europe (PRACE) for creating the distributed supercomputing infrastructure that will be able to be accessed not only by scientific institutions but also schools, businesses and governments, and the SAGE project for developing a multi-tiered storage platform for data-centric exascale computing that will enable data to move seamlessly between the tiers.

Griffiths said the EU and member states will spend more than €1 billion over the next several years to push the exascale effort, which will come with two pre-exascale systems between 2021 and 2022 and two exascale systems in 2023. There also was a focus put on Mont-Blanc, the supercomputer launched in 2015 as a three-year project and housed at the Barcelona Supercomputing Center with the goal of building an HPC system using Arm’s low-power 32-bit chip architecture. The project is now evaluating the power-efficient architecture for use in a pre-exascale system while it also is working on the Dibona platform built by Atos/Bull and powered by Cavium’s ThunderX2 chips based on the 64-bit ARMv8-Aarchitecture. That platform should be ready by sometime next year, according to Etienne Walter, coordinator of the Mont-Blanc Project. Dibona will be based on Bull’s Sequana X1000 servers.

Be the first to comment