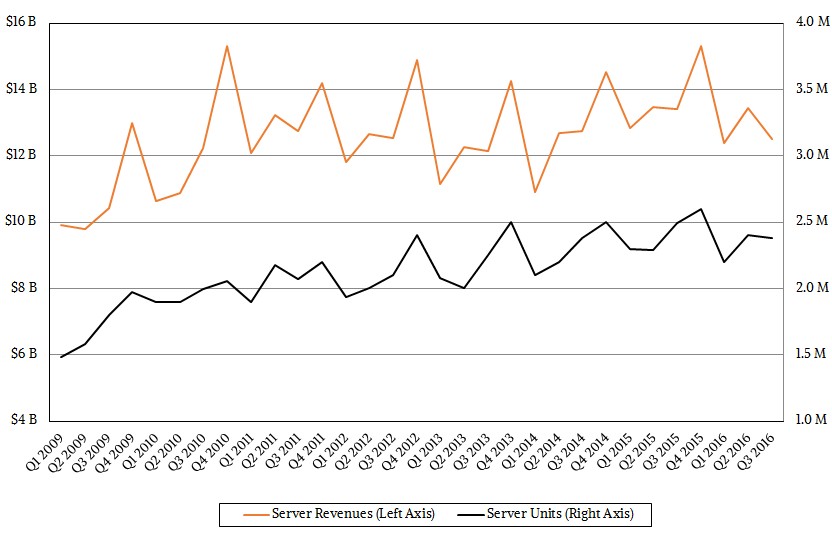

If you happen to believe that spending on core IT infrastructure is a leading indicator of the robustness of national economies and the global one that is stitched, somewhat piecemeal like a patchwork quilt. From them, then the third quarter sales and shipments of servers is probably sounding a note of caution for you.

It certainly does for us here at The Next Platform. But it is important, particularly if we have in fact hit the peak of the X86 server market as we mused about three months ago, to not get carried away. A slowdown in spending amount some hyperscalers and cloud builders at the same time that enterprises are pulling back a bit is alarming, for sure, particularly as Intel is getting ready to launch its “Skylake” Xeon processors in the middle of next year and IBM is getting ready to follow suit with Power9 chips in the second half of 2017. AMD will be rolling out its “Zen” Opterons next year, too, a bunch of new ARM server chips are coming down the pike, and Nvidia will be debuting its “Volta” GPU accelerators. Various FPGAs will be coming to market or ramping from Intel and Xilinx as well. To say that 2017 is going to be an exciting year for compute is an understatement. With all of the custom processors also being developed for parallel processing and deep learning, to call it a Compute Cambrian Explosion is not hyperbolic at all. Even if Fujitsu has stopped development on Sparc64 chips and Oracle is rumored to be preparing to mothball Sparc chips or the Solaris Unix operating system, or both.

Let’s talk about the numbers for the third quarter and try to sort this out, and we will start with what the box counters at Gartner think happened, and then we will look at IDC data. Both count the server market a bit differently, and across the two we can get a sense of what is happening. (Gartner looks at spending from the end user perspective, and IDC looks at vendor revenues into their channels plus their direct sales. In a perfectly balanced channel, these would be the same number, but the channel doesn’t work that way as it acts as a buffer between customers and suppliers.)

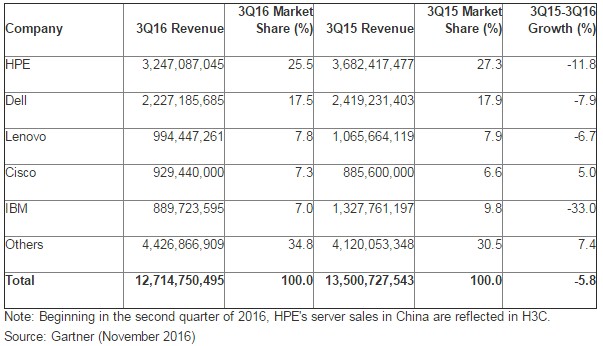

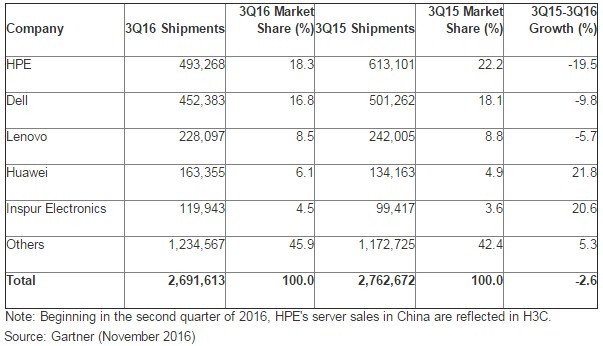

According to Gartner, in the third quarter companies consumed $12.71 billion in server gear, down 5.8 percent from the year ago quarter, with shipments down 2.6 percent to $2.69 million units. While Hewlett-Packard Enterprise remained the top server seller in the world, selling off its Chinese server business to the H3C unit of Tsinghua University had an adverse impact on its direct shipments and therefore its direct revenues. As a consequence of the server downturn and the selling off of this business in China HPE’s shipments were down 19.5 percent to 493,268 in the quarter, and despite higher average selling prices for machines, HPE’s revenues were pulled down 11.8 percent to $3.25 billion. That gives HPE 18.3 percent shipment share and 25.5 percent revenue share.

Here is how Gartner believes the revenues stacked up globally among the top five:

And here is how they stacked up based on shipments:

There are a couple of interesting things to note. First, Dell is closing in on HPE in terms of shipments thanks to the H3C spinoff, with 452,383 machines shipped in the third quarter, but HPE still has a considerable revenue lead with Dell only converting those machines to $2.23 billion in revenues. Like Dell and HPE, Lenovo also shrank revenues faster than the market at large, but by less than its two bigger rivals and its revenues kissed $1 billion driven by 228,097 units shipped. HPE’s units shrank five times faster than the market, Dell by four times, and Lenovo by two times. All three are being impacted by the success of Inspur, Hauwei, and Sugon in China and, increasingly, in Latin America. Inspur and Hauwei broke into the top five shippers a few quarters ago and are now solidly going to stay there unless something really dramatic happens with IBM’s Power Systems business. IBM has not shipped more than a 100,000 units of Power-based servers in a year in a very long time, much less in a quarter. So unless someone like Google and Rackspace and a few HPC centers and big enterprises go nuts for Power9 machines, Huawei and Inspur are going to keep their shipment rankings. Cisco Systems is still growing revenues thanks to enterprise customers buying rich configurations, but it does not peddle as many nodes as the two big Chinese server makers. Cisco grew its revenues 5 percent to $929.4 million in the period, bucking the trend among the top tier server OEMs, much to its credit.

IBM, which no longer has a System x Xeon server business and which is at the tail end of the Power8 system and System z13 mainframe generations, is having trouble pushing gear. Revenues were down 33 percent to $889.7 million. Three years ago, in the third quarter of 2013, when IBM still had an X86 server business, it booked sales of $2.82 billion. A year later, as the selloff to Lenovo of its System x division was being done, sales slipped to $2.32 billion, and a year after that, in the third quarter of 2015, they fell a lot further to $1.33 billion. Over that time, IBM’s revenue share of the server space has fallen from 22.8 percent in 2013 to 7 percent in the most recent quarter. And this is from a Big Blue that aspires for the Power-based server business, including its own and that of its OpenPower partners, to have at least 10 to 20 percent shipment share of the aggregate global server market. IBM has a faction of a percent of global shipments today, and probably ships about two to three as many servers as the ARM collective does, just to give you perspective.

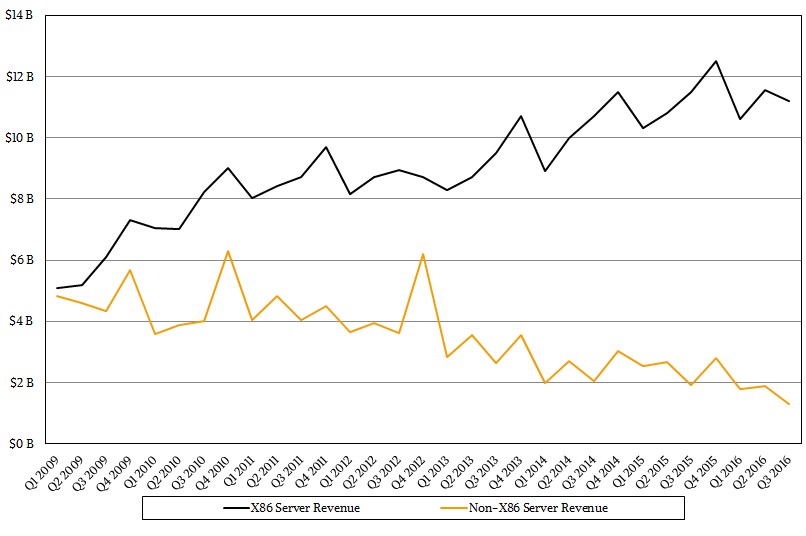

The interesting bit in the Gartner numbers is not the slow and steady decline in the Unix server business, which has been proceeding at pace for the past decade and a half after peaking in the dot-com boom, but that Gartner shows the X86 server business actually declined in both revenues and shipments, the first time that has happened since the Great Recession when everything went into the ditch in the server world. Unix system shipments were down 37.7 percent to 14,485 units and revenues fell by 38 percent to $658.2 million. But the powerhouse of the datacenter, the data closet, and under the desk, that X86 machine, had a 2.3 percent shipment decline to 2.67 million units, and revenues fell by 1.6 percent to $11.34 billion. Among X86 suppliers, only Huawei and Inspur had shipment growth in the third quarter, and only Cisco had revenue growth.

The X86 server increased its share of the server revenue pie to 89.2 percent and the server shipment pie to 99.3 percent. We have said it before, and we will say it again: These kinds of numbers, for no technical reasons, cannot hold with an Intel that has 50 percent gross margins in the Data Center Group. That kind of market share and profit will bring ever more intense competition, and Intel can only do what it is doing – become its own best competition.

Would it not be hilarious if Intel commercializes ARM servers best someday? Stranger things have happened, and will happen. Particularly if any big part, or several parts, of the world slip into recession in 2017. It has been a decade, after all, and the Dow Jones is at a peak along with X86 server sales, and nation after nation is turning inwards and getting protectionist. Instead of a housing crisis, an identity crisis could cause the next recession, and Intel might not fare as well this time as it did when the “Nehalem” Xeons launched into the gaping maw of the Great Recession. We are all more sophisticated when it comes to infrastructure these days.

Over at IDC, there is consensus that the server market softened a bit in the third quarter. The other professional box counter says that factory revenues for servers across all vendors was off 7 percent to $12.5 billion, and that shipments fell by 4.6 percent to 2.38 million. The healthy “Haswell” Xeon server ramp in 2015 has made for some tough compares, and so has a slowdown among hyperscalers, cloud builders, and enterprises.

IDC tracks servers by market segment as well as by processor architecture, and in the third quarter, volume servers, which cost $25,000 or less a pop, had a revenue decline of 4.9 percent, to $10.3 billion. Midrange machines, which cost between $25,000 and $250,000, had a 4.1 percent decline to $1.1 billion. High end servers, which include IBM and other mainframes as well as big RISC, Itanium, and Xeon NUMA servers, declined by a staggering 25 percent to $1.1 billion.

By architecture, X86 machines dominated, with IDC saying that machines using mostly Xeon processors accounted for $11.2 billion in sales, down 3.1 percent, and shipments came to 2.36 million units, down 4.3 percent. Machines using other processor architectures, including Itanium, Power, Sparc, ARM, and a smattering of others, drove $1.3 billion in revenues, but fell 30 percent year on year. X86 iron, by IDC’s numbers, had a 99.2 percent shipment share and an 89.6 percent revenue share.

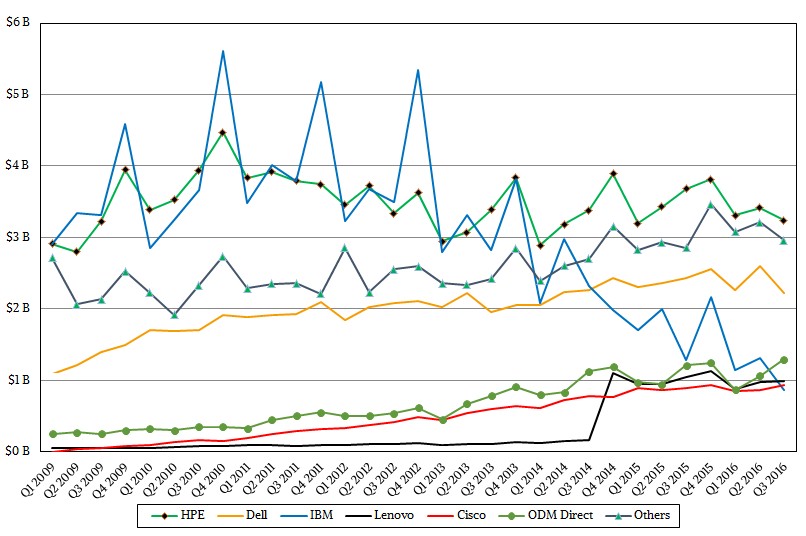

The vendor breakdown by IDC is similar to that of Gartner, with the exception that IDC breaks out ODM direct sales to companies like the big hyperscalers and cloud builders. Take a look:

Here is the interesting bit of the IDC data. The ODM server makers like Quanta Computer, WiWynn, Stack Velocity, Tyan, and a few others posted revenues of $1.3 billion in the quarter against $11.2 billion for OEMs, accounting for 10.3 percent of total server revenues worldwide. In the second quarter of this year, ODMs had $1.9 billion in sales against $9.7 billion for OEMs, or 13.9 percent of the revenue total. If you look at the trailing twelve months, OEMs have $5.3 billion in server sales, up 22.1 percent compared to the period running from the fourth quarter of 2014 through the third quarter of 2015. During that same time, all other server makers saw a 5.7 percent decline to an aggregate of $53.6 billion in the trailing twelve months.

But don’t get ahead of yourself. The ODM data above does not include sales of custom iron made by Dell, HPE, Lenovo, Inspur, Sugon, and other OEMs. So ODM does not directly equate to hyperscaler plus cloud builder. What we think this shows, by the way, is that the hyperscalers and cloud builders that use ODMs are increasing their spending (Google, Facebook, and Amazon Web Services are the big ones) while those that are buying from the custom server divisions of the OEMs (think Microsoft Azure and its strategy of working with Dell and HPE to build a lot of its iron) are apparently slowing down. A slowdown in spending by Microsoft ahead of the Skylake Xeon launch and as it creates its new Project Olympus server platform that is designed for these processors as well as GPU and FPGA accelerators, stands to reason. You would wait for all this new compute in a new server design, too, if you were trying to build out massive datacenters like the ones in Quincy, Washington that we recently visited.

There are a few other factors at work here. Just like there was a virtualization downdraft when VMware ESXi, Microsoft Hyper-V, and Red Hat KVM took off in the enterprise datacenter just as the Great Recession started, we think that cloud-style computing, with sophisticated provisioning, orchestration, and management, is causing a bit of a downdraft in compute capacity. It is not that the capacity is going down – it absolutely is not – it is just that it is not growing as fast as it otherwise might as companies get more efficient. AWS and Microsoft have both bragged about how they could slow down spending because they could make better use of the compute, storage, and networks they buy, and enterprises are learning tricks, too, as are service providers and telcos.

There is another factor in this pressure on server shipments and revenues. It is more profitable to sell higher level PaaS or SaaS stuff than raw IaaS. The cloud providers that have more than IaaS can basically charge for the underlying infrastructure and then a premium for the service that runs on top of that. Companies that build their own services will, as they did in their datacenters, overprovision their capacity because this is human nature, but the cloud providers will not do this above and beyond the overprovisioning they already do. The net effect is that they buy less infrastructure than they might otherwise and they squeeze more work – and more money – out of that infrastructure, too.

Finally, we think that we are witnessing the effect of a substantial shift of workloads from private datacenters to clouds. This provides a double whammy. OEMs lose the sale to the datacenter and the ODMs and the ODM-like units of the OEMs gain them, and the workloads, as a group across these enterprises, run on less shared infrastructure (more efficiently in the terms of the aggregate capacity used, not in the speed of the individual apps) and therefore the server count is that much lower than it might otherwise be.

This slowdown is not as simple as enterprises pulling back. This is infrastructure transforming, exactly as we all planned. And maybe, if we are not lucky, the beginning of a recession.

Well if AMD with Zen can get some of that x86 market share via AMD’s price/performance metrics in its Zen server room SKUs, AMD will most definitely have increasing revenues year to year from now on! Enough of that Zen information has been revealed with even more to come Dec 2016 with AMD’s “New Horizon” event. Short of some real benchmarks done by independent third parties Zen has pretty much been gone over at this years Hot Chips symposium, save some off Zen Cores(4 Zen cores per complex/CCX) connection fabric information.

Lack of any information on the other Jim Keller lead CPU project besides his x86 design teams’ Zen CPU has me more concerned. AMD’s custom K12 ARMv8A ISA running micro-architecture has had very little attention in the press, and very little attention from AMD on the announcement side also. I guess that AMD is really having to focus on x86, as baby really needs a new pair of shoes and that horse’s name is Zen. But it would be very nice indeed if AMD could field a custom ARMv8A ISA running micro-architecture that had SMT capabilities for the server market. Zen is getting the SMT treatment and like Intel’s version of SMT(HyperThreading) Zen should be able to get at that 15-30 figure on extra performance that Intel gets with its SMT enabled cores. So a custom ARMv8A ISA running micro-architecture from anyone in the custom ARM based server SKU market should be able to get at the 15-30% extra performance metric if they will just Bring SMT to a custom ARM RISC ISA based design.

IBM’s RISC ISA based power CPUs, Power8’s and now Power9s, make heavy use of SMT up to 8 threads per core on the Power8’s and the Power9 expected to come in SMT4, with more CPU cores, or SMT8 and less cores, for 2 Power9 variants(SMT4 and SMT8). SMT hardware in a CPU’s core allows for a more efficient use of available CPU core execution resources if one of the 2 minimum processor threads required for an SMT enabled core stalls the other processor thread can be quickly context switched over and worked on while the other stalled processor thread waits for whatever dependency that caused its stall in the first place to be resolved so it can be context switched back in and worked on.

Why any of the custom ARM server CPU makers have currently not considered SMT as of yet is unclear but maybe it’s something to do the difficulty of engineering SMT ability into a CPU’s core, and even Intel did not invent that IP used for SMT(Simultaneous MultiThreading) on modern microprocessors. Maybe in 2017 after the Zen fanfare has died down we will see just what the Jim Keller lead K12 design team did with that custom ARMv8A running micro-architecture. We already have plenty of information about Zen, but is AMD’s K12 project dead or alive.

I think that a lot of the server market’s clients are playing a wait and see game with hopes that Zen will be a hit with that price/performance metric for those who have too much currently invested in the x86 software ecosystem, while others are maybe kicking OpenPower’s wheels for any Power8/Power9 usage. The ARM server market has not had the expected growth curve but there still some potential there and in the server/HPC/exascale market via the Japanese and ARM Holdings(SoftBank) connections to the ARM IP/software ecosystem. Some of the server clients may even be playing the Power9 and other Zen card options to Intel in order to get better deals so they may be playing wait and see and Blind man’s bluff (poker) for a better deal.

Their Naples SoC will come in the middle of 2017, and AMD will have to wait for the customers to run some tests, perhaps 6m to 12m(plus around 50 to 100K chips for free). Intel already have some samples of the Purely SoC Xeons, so this price thing is not something I will be looking forward to. In 2017 Intel will sample Xeons on 10nm processing node, so another 2-3years advantages over AMD in the server market. AMD needs to bankrupt so we in the tech industry will see a better shiny/bright days ahead.

I think that power9 will be a agreat success. I’m intrigued about the new uarch announced at hotchips.They said it is even more efficient than smt. Let’s see. 2017, a good year for new chips!

Certainly there is increasing efficiency and always has been. On that old IDM sales rep observation if OLTP system improvement to fully utilize the installed base, there would be no need for new system sales. Although there appears a robust network processing market including too off load from compute some network analytic and data pre-processing.

And this is why, Intel gold;

Broadwell E5 2600 marginal revenue potential at $1K / 2 = $19,356,125,216

Haswell E5 2600 marginal revenue potential at $1K / 2 = $15,753,602,553

Ivy Bridge E5 2600 marginal revenue potential at 1K / 2 = $41,178,506,902

On the question is there a general server slowdown;

Recall Intel began Xeon architectural period doubling at v3. In relation to the combined Broadwell + Haswell production runs determined on Intel supply signal data, annual revenue and unit volume compared too Ivy Bridge is down 20%.

On signal cipher data, ending i2014 – 2015, volumes are 60% Ivy Bridge E5 2600 v2 and 40% Broadwell + Haswell v4/v3 combined.

On product run revenue potential, Broadwell + Haswell on supply signal data is down 8% in relation to Ivy Bridge; 54% Ivy Bridge E5 2600 v2, 46% Broadwell + Haswell v4/v3. However adding E5 4600 v2 and E7 v2 revenue the Ivy Bridge difference is substantially greater.

There is currently a robust 4600 v2 market on average weighed price shown at Intel $1K; E5 4600 v2 = $1741, 4600 v3 = $3856, 4600 v4 = $3735. Intel pricing for 4600 v3/v4 discouraged upgrade and volumes are way down.

All Multiprocessing availability on broker inventories through prior 168 weeks:

E7 v2 8 way; 3.14% of total broker availability

E7 v2 4 way; 15.32% of MP

E7 v3 8 way; 2.44%

E7 v3 4 way; 1.94%

E7 v4 8 way; 0.10%

E7 v4 4 way; 0.05%

All E5 4600 v2; 74.71% of MP

All E5 4600 v3; 2.26%

All E5 4600 v4; 0.04%

E5 2600 DP broker stocks in relation to full run volumes; Ivy at 168 weeks of supplies, Haswell at 117 weeks, Broadwell at 38 weeks –

Broadwell at 38 weeks is currently 10% of products through broker channels with Haswell representing 40% at 117 weeks of supply and Ivy Bridge representing 50% at 168 weeks of available supply.

All grades are trading. In the last week 99% of all accumulating Ivy 2660 and 2695 that in second half swelled to represent 33% and 22% of the category total, are purchased.

Watch out for the MacPro knock offs and Ivy Xeon portrayed as Broadwell Extreme this holiday sales season. Not that that would be a bad purchase, just know what you’re buying on BIOS, chip set support and cooling.

Haswell v3 broker holdings have not seen same trend on 2603, 2609, 2620, 2630,2640 and 2650 inventory ramp now representing 37% of broker inventories for November; 9%, 2.78%, 4.48%, 9.67%, 1.38%, 8.44%, 1.28% respectively.

E5 4600 v2 also realized a large sell off week of 11.28 at 98% of available. E7 v2 is similar showing a 90% decline in availability. In the next months time will tell how much resurfaces in the channel.

Following Westmere the trend is interest in older MP this analyst attributes to substantially higher v2 volumes, discounting, mature applications base and the said Purely one socket fits all DP / MP variants.

For Enterprise why buy new?

There is so much great older product why take Intel price when you can make an open market procurement; components or servers coming off lease. Closer too Purely more reason to wait; might as well buy back in time on price performance for established applications use.

If it works don’t fix it. And certainly don’t break it.

Plus the whole network reengineering thing remains a work in progress and if you’re core competency is not the business of compute, adaptation as an early adopter can be costly and time consuming. Best too wait on those expert determinations?

Second half change in Xeon E5 2600 Monthly Broker Market Channel Inventories;

E5 2600 Broadwell v4, Haswell v3, Ivy Bridge v2 only –

October to November; BW up 2%, HW down 3%,IB up 5%

September to October; BW down 12%, HW up 5%, IB down 26%

August to September; BW up 137%, HW up 90%, IB up 22%

July to August; BW down 4%, HW down 33%, IB down 27%

Weekly average holdings; 25% Ivy E5 2600 v2, 53% Haswell, 22% Broadwell

Broadwell mean volume per quarter up 30%.

Haswell mean volume increase per quarter up 14%.

Ivy Bridge mean volume per quarter down (6.5%).

Examining supply pattern Intel 2nd half Broadwell press drives prior generations into broker channels.

This really put the competitive crunch on ARM camp where Intel supplied E5 2600 v4 8 core line at a $274,186,858 marginal revenue sacrifice to produce that specific core grade SKU, or about $44.14 per unit of production less than the marginal cost of producing the 8 core grades SKU. There after Intel prices on average at 1K $504.

In relation to 12/10C average weighed 1K price at $964.30, on that average the Intel 8 core line is priced artificially low by $386. At a 50% IDM discount on 8C average is $252. Throwing DP workstation 2667 out of the average, as well as 2608L that no one seems to want, 2609 and 2620 AWP (average weighed price) is $362.

On the divide by 2 best IDM discount rule then 8C $180.75 on average; 2609 at $153 and 2620 at $208. Still above cost, in doing so Intel purposefully reduces industry revenue for all competing 8 core products at $1K / 2 or $2,796,209,828. That sum is roughly AMD cost to produce revenue of $3.991 billion for 2015. For Applied Micro and Cavium, represent 94% and 84% greater than their 2015 revenue’s respectively. And that is called Intel predation.

For those who would compare on the 10C 2640; $1K $939 / 2 = IDM $469.50, well, confronted with a competitive sales situation Intel can still reduce the volume price on that specific SKU to $153 where P = C.

Power is in a different situation justifying price on the performance of 65 years of structured data processing that goes well with very large cache size.

There is some thinking, re-grouping, re-architecting.

Mike Bruzzone, Camp Marketing

As an addendum what’s really interesting on 2600 v4 8 core total revenue by marginal revenue sacrifice, is the same strategy, a repeating pattern on Woodcrest dual, Clovertown quad, Lynnfield quad, Haswell hexa and Broadwell octa. Off the top of my head not going back through the calcs.

These industry revenue deprivations are one among the 15 USC 2 Sherman Act proofs; intent by conduct to monopolize.

The issue with Section 2 proofs is established case precedent.

Section 1 cases like price fixing are proven on case law precedent that are prior determinations; per se.

Section 2 determinations are subjective that lead to case precedent determination affirmatively resolved.

On U.S. case decisions, $37,302,000,000 prior 23 year Intel inside route fee transfer toll way charge procurement price fix theft is established; 10 years back recoverable on EUCC C3 / 37.990 decision on U.S. case precedent establishing RICO; that is proven in the federal and states investigative record.

The issue with Sherman Act Section 2 intent to monopolize proof is established by legal judgment on case precedent to be heard v the pure Sherman Act 15 USC 1 violation that is Intel Inside. There after the affirmed precedent moves to Section 1 status.

That is the reason for the House Oversight and Government Reform Committee ‘Intel Fraud Act” a proposed Congressional Legislative enactment all members of United States Congress, USDOJ, FTC, White House, national security, inter nation security, State AGs and 82 consumer actions are aware

Mike Bruzzone, Camp Marketing