Making storage cheaper on the cloud does not necessarily mean using tape or Blu-Ray discs to hold data. In a datacenter that has enormous bandwidth and consistent latency over a Clos network interconnecting hundreds of thousands of compute and storage servers, and by changing the durability and availability of data on the network and trading off storage costs and data access and movement costs, a hyperscaler can offer a mix of price and performance and cut costs.

That, in a nutshell, is what search engine giant and public cloud provider Google is doing with the latest variant of persistent storage on its Cloud Platform. We say “seems” because Google will neither confirm nor deny what specific technologies are being deployed with its new Coldline storage, and even colder and in some ways cheaper form of object storage than the Nearline storage it announced back in early 2015 and that we discussed in detail at that time. None of this means that Google doesn’t use massive robotic tape or Blu-Ray libraries; for all we know, it does this, too. But we think the new Coldline storage is just a variant of the Nearline disk drive theme, and yet another example of why Google needs better disk drives, as it has suggested to the industry. In 2015, Google YouTube users are uploading around 1 PB of data per day, and that capacity demand was growing exponentially. Google has no doubt engineered some very clever storage servers with excellent price/performance to meet that demand – although it won’t brag about them until many years from now, if ever. Cloud Platform is a beneficiary of the innovation that Google does in compute, networking, and storage, and therefore its users benefit, too. The density and performance required for a video streaming storage server no doubt can be applied to object storage workloads, too.

Dave Nettleton, the lead product manager for storage for Google Cloud Platform, was not giving away much when we pressed about the underlying technology used for Nearline and Coldline storage.

“We look at all kinds of media and technologies in the market,” Nettleton tells The Next Platform. “We also invest in our own server hardware and networking infrastructure, and having such a big footprint means that we have understandings of costs, throughput, and latency on a global scale, and that means that when we look to make investments to reduce costs and improve experience, we can afford to invest in dedicated hardware to accomplish that. So we look at every type of technology that you can imagine and invest in innovation on our own.”

We do know from talking to Google in the past that the object storage services that Google Cloud Platform offers are based on a mix of flash and disk media, and that the secret is that Google has a consistent way of abstracting that storage through APIs for access to data and, perhaps more importantly from its point of view, allows for it to program differentiated levels of service for that data rather than having to move it from hot to warm to cold clusters that are separated from each other. This is what gives Google economies of scale on its storage.

The whole point of Google’s Clos network, and all of the hyperscalers have created networks with Clos topologies for their warehouse-scale facilities, is that everything is interconnected in a such a way to provide a very large bi-section bandwidth and relative consistency in the number of hops between machines on that vast network. So Google is probably not taking an old datacenter off to the side somewhere and turning it into a Coldline or Nearline storage farm. We think the differences in latency for various Google storage services certainly have something to do with the processing and I/O capacities of the storage servers and their disk (and probably sometimes flash) drives, but the different levels of availability and access time have more to do with network management for Google than anything else. If Google can allocate some of its storage as Nearline or Coldline, that part of its network won’t get so hot, and if it does, customers will pay a hefty premium for that network access to their archival data.

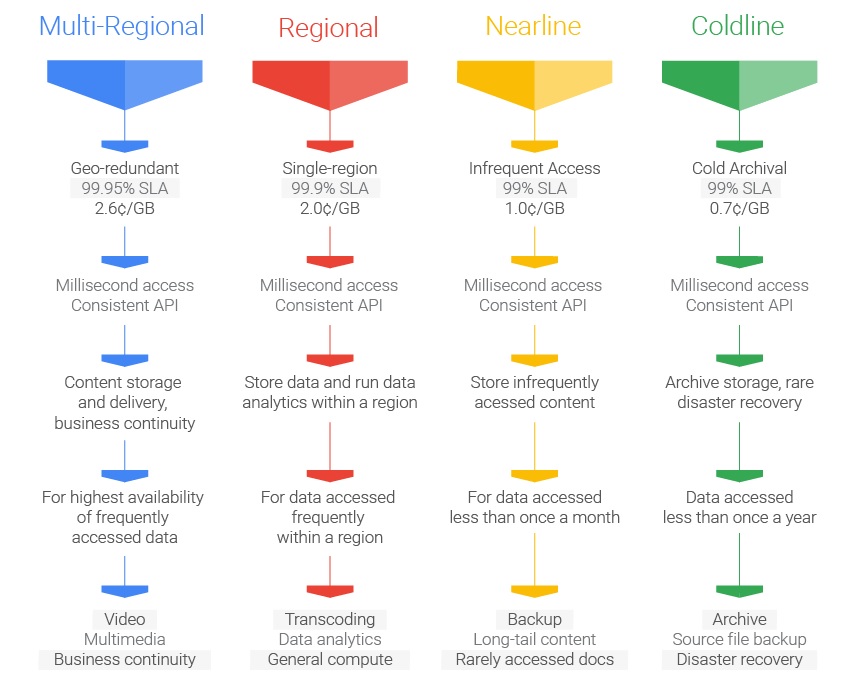

Google has rejiggered the storage services on Cloud Platform to reflect the benefit coming from that network and the consistency and scale across its storage server farms. There are two new storage types, called Regional and Multi-Regional, that are augmenting its Standard storage type, and the Durable Reduced Availability storage, a kind of less reliable storage service that predated Nearline, is being sunsetted. As part of the tweaking of the storage services, it looks like Google is guaranteeing millisecond-level access times across its storage services and no longer differentiates based on this metric – or at least not on the same level as it has.

Some review is in order so you can appreciate the changes. Up until now, here is how Cloud Platform’s storage lined up, with variations on cost per unit of capacity, cost of data access, and latency to, bandwidth from, availability of, and durability of the data that is stored on those services. First and foremost, as is the case with all cloud providers, it is always free to upload your data into Google Cloud Platform’s storage services. That is a bet by Google and others that once the data comes in, it will never leave.

Standard storage on Cloud Platform has eleven 9s of durability, which means Google is 99.999999999 percent certain it will not lose a chunk of data because it replicates it across its network of storage servers. The availability for Standard Storage is three 9s (which means Google is saying you will be able to get to that data 99.9 percent of the time which is another way of saying it allows itself as much as 8.8 hours of downtime a year), and had a guaranteed bandwidth out of the storage of 10 MB/sec per TB of capacity. (Bandwidth multiplies linearly with capacity on the Googleplex, thanks in part to that Clos network.) Standard storage services offered access times of around 100 milliseconds for the time to first byte, which is a more precise number we were able to get out of Google last year and which you won’t find elsewhere. Standard storage cost 2.6 cents per GB per month, and there are no fees for reading data.

For the now-discontinued DRA storage, Google kept the bandwidth and access time the same as with the Standard service, but availability had one nine knocked off to 99 percent (which means it could be inaccessible by as much as 3.65 days per year). By accepting that lower availability, customers could store data in the DRA service for 2 cents per GB per month, similarly with no additional fees for reading data.

The presumption with both Standard and DRA storage is that they house hot data and you have already paid for the reads. (In a way, Standard customers are paying 1.6 cents per GB per month for reads and DRA customers are paying 1 cent per GB per month for reads, whether or not they use that much access, based on the pricing of Nearline storage.) With colder data, the presumption is that customers want a lower price so they can store lots more of it, and that it will be accessed a lot less frequently. But Google still have to pay for the underlying iron and its power, cooling, and space, and therefore there is a fee associated with accessing data on both Nearline and Coldline storage.

With the Nearline storage service announced last year, access time was knocked down to no less than 2 seconds and no more than 3 seconds, and the bandwidth out of this storage was lowered to 4 MB/sec per TB of capacity. Availability was set the same as for the DRA service, which was 99 percent available. For accepting these metrics, Google chopped the price down to 1 cent per GB per month, but there was an additional charge of 1 cent per GB for accessing data.

The pricing, availability, and durability of the data on Nearline storage has not changed with this set of announcements, but Google is now saying access times for time to first byte are now “milliseconds,” not seconds, as you can see in this table:

We were not able to find out precisely how many milliseconds Nearline storage has as its access time, but there is no reason to believe, given the fact that everything is running on the same networks and underlying hardware, that it is on the order of 100 milliseconds like Standard storage.

The new Coldline storage service has roughly the same latency for first time to byte, Littleton confirmed to us, as the tweaked Nearline service. Coldline costs a bit less at seven-tenths of a penny per GB per month compared to 1 cent per GB per month for Nearline, but data access fees are a five times higher at 5 cents per GB. So you really have to think about where you are going to put your data and how frequently you are going to access how much of that data. The SLA for Coldline is the same as nearline at 99 percent, and we presume the bandwidth is the same at 4 MB/sec per TB of capacity, but Google did not confirm this.

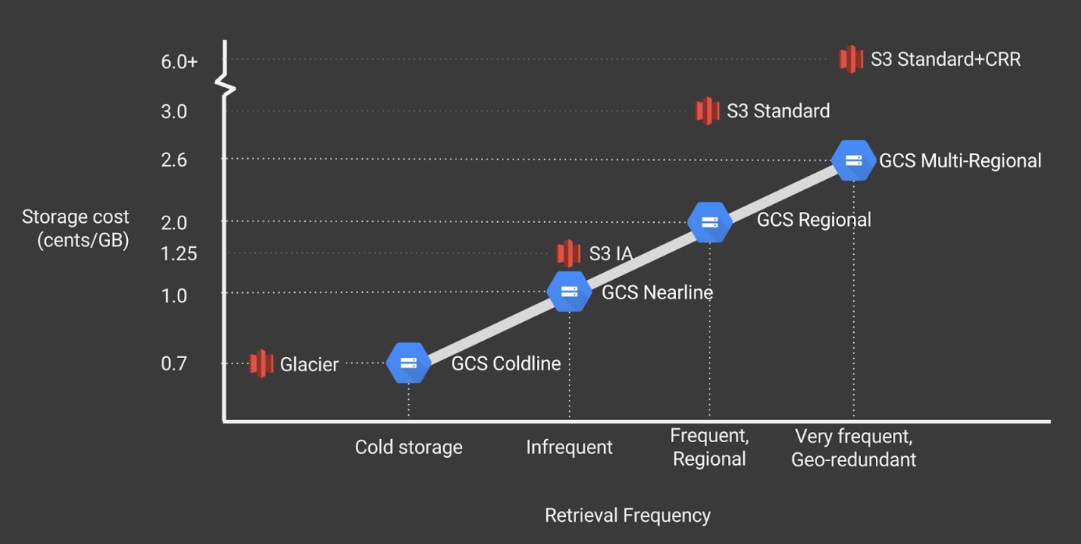

While Coldline is not all that much cheaper than Nearline (30 percent less costly), the significant thing is that the price for Coldline is the same price as the Glacier archiving service from rival Amazon Web Services. And Glacier has a much longer latency, at a whopping 3 to 5 hours to the time the first byte is accessed. This very large latency is why many people believe that AWS is using tape libraries as the foundation for the Glacier service, but there seem to be an equally large number of people who believe Glacier is based on old disk-based storage servers on the far ends of its datacenter. (It could be a combination of disk, tape, and Blu-Ray disk.)

While Google has not taken away its Standard storage, it has replaced Standard and DRA with services with what it is calling Regional and Multi-Regional services. The Regional service offers 99.9 percent availability of access to the data, like the Standard storage, and costs 2 cents per GB per month, just like the DRA service Google used to sell. So in effect, Google is dropping the price on Standard storage by 23 percent and giving it a new name. We presume the same 10 MB/sec per TB is holding for the Regional service as was offered for the Standard service and that the same 100 milliseconds to get to the first byte of data also holds.

For customers that need a more distributed set of data to feed customers around the globe or to provide higher availability to data access, Google is now offering Multi-Regional storage, which as the name suggests automatically distributes data across multiple, dispersed regions in the Googleplex of datacenters. With Multi-Regional, service level agreements guarantee access to data 99.95 percent of the time, a significantly higher level compared to the former Standard storage. (That equates to 4.38 potential hours of downtime a year before Google has to give your money back.) This Multi-Regional storage is available in regions in the United States, Europe, and Asia, and includes routing between regions with the attendant extra latency that would be incurred if customers accessing that data are further away. We presume that the access from within a Cloud Platform region is the same 100 milliseconds, as it was with the Standard service, and similarly Google is guaranteeing 10 MB/sec per TB between the storage and its Compute Engine instances when they are located in the same region. (There is no reason to believe this would change.) In essence, Google has just added free geo-replication across regions to its Standard service and cut potential downtime by almost half.

Google is also putting into beta a set of tools that can be used to automatically move data to its four different types of storage. For those who need even lower latency access to hot data, Google suggests that customers get flash instances on Compute Engine.

That Google is offering colder and colder storage with lower and lower pricing begs another question: What will the company do to offer storage services that are hotter and hotter? With OpenCAPI and Gen z laying the groundwork for attaching blocks of storage class memory to systems and racks, it seems reasonable to ponder a day when Google will offer storage services based on flash, 3D XPoint, or whatever non-volatile memory it helps commercialize. (And yes, Google will help determine which technologies succeed based on their feeds, speeds, and prices.)

“We are always talking to our customers to understand what they are looking for,” says Nettleton. “We are always looking for ways to improve things.”

So that is a definite possibility of a probable maybe on storage services external from Compute Engine servers not based on disks and driven by new memories.

The lesson to learn from the way Google does object storage is to pick one thing and scale it massively, using software to provide different classes of service and chargeback to different classes of applications. We have not heard of an enterprise-class object storage system that does what these four services offer, but this is clearly something that the Global 2000 would want to buy, particularly if the movement between different classes of storage was automated. The way Google and its cloud peers price for data access also suggests that enterprises should be doing something very similar in terms of motivating users to really think through what they are saving, and prices for data storage and access certainly help shape behavior a lot more than just installing a collection of different gear and letting everyone just fill it up as fast as possible. The same rigor that cloud providers enforce on their customers should be de rigeur in the corporate datacenter.

Author’s Note: Dave Nettleton just joined Google in September, but he is no stranger to sophisticated storage architectures and databases. Back in the early 2000s, Nettleton worked at Microsoft on SQL Server and the Windows Future Storage (WinFS) file system that heralded the merging of the file system with relational database technologies to allow unstructured, semi-structured, structured data alike to be queried like a database. Before leaving Microsoft, Nettleton was put in charge of Azure Storage on Microsoft’s public cloud as well as HPC development on that cloud, and for last five years at the software giant was in charge of the SQL Server database services and related analytics on Azure.

Be the first to comment