One of the reasons why Dell spent $60 billion on the EMC-VMware conglomerate was to become the top supplier of infrastructure in the corporate datacenter. But even before the deal closed, Dell was on its way – somewhat surprisingly to many – to toppling Hewlett Packard Enterprise as the dominant supplier of X86 systems in the world.

But that computing world is set to change, we think. And perhaps more quickly – some might say jarringly — than any of the server incumbents are prepared to absorb.

After Intel, with the help of a push from AMD a decade ago, created what has become an almost universal substrate of general purpose compute, the ever-persistent demands of memory bandwidth, thermal and compute efficiency, and price/performance improvements seem destined to fragment computing and spread it around myriad devices and embedding it different layers of a system, a cluster, and a platform. We are, we think, right at Peak X86, in fact, and to be perfectly blunt, it will be hard for Intel and its partners to increase their revenue and shipment share of compute in the datacenter and on the edge of the network reaching out from them.

The intense competition between the players in the X86 server market is, in a way, a kind of leading indicator for a tectonic change that is set to come. The hyperscalers and cloud builders call the tune to Intel and their respective server builders, whether they are OEMs or ODMs, and they represent an increasing portion of the server capacity installed in the world; they also drive product features and product cycles, and more significantly, they will do anything to beat each other and try to get ahead of Moore’s Law improvements in the X86 architecture, even if that means switching processor and system architectures.

This is, in a way, a new dawn for system architectures, and it is exciting even if there is, by the very nature of the situation, more risk involved with picking compute components and weaving them into a platform. No one ever got fired for buying a cluster of two-socket Xeon servers, after all.

It is with this backdrop that we examine the latest server stats from Gartner and IDC.

Given this Peak X86 situation, it is not a surprise at all to us that the gap between HPE and Dell has closed quite a bit in the second quarter. With IBM leaving the X86 field two years ago, these two companies have been wrestling with each other for market dominance while at the same time have struggled to fend off the onslaught of fierce competition among makers of systems in Taiwan and China that crave a much bigger piece of the datacenter pie, too. All of the major players are fighting for a piece of the hyperscale and cloud build out, and big shifts in market share are happening each quarter as deals get done or are pushed out.

The analysts at Gartner measure the revenues and shipments out of vendors for direct sales added to box shifting done through partner channels, while IDC estimates the vendor factor revenue either to direct customers or into the channel. They are not exactly the same data, but are similar. They also dice and slice the market differently, at least in their publicly available data, and looking at both sets of information gives a kind of 3D view of what is happening out there in Server Land.

In the quarter ended in June, Gartner reckons that the overall server market was down eight-tenths of a percent to $13.55 billion against shipments that grew by 2 percent to 2.76 million units worldwide. As has been happening since the dot-com bust, the Unix systems market continued to decline, and the IBM mainframe, which is at the end of its System z13 product cycle, is also waning a bit until new iron comes out (most likely in 2017). X86 systems – which in essence means Intel Xeon platforms since AMD does not really have a systems business at the moment despite its hopes for the future — are where the real growth is, and were it not for the massive buildouts among hyperscalers and cloud builders, we think even the X86 part of the systems market would be in slight decline.

But thanks to the hyperscalers and cloud builders and the many smaller service providers and telcos that are trying to emulate them, the X86 systems market continued to grow, according to stats from Gartner. Revenues rose by 5.8 percent across all OEMs and ODMs, to $11.73 billion, while shipments rose by 2.1 percent to 2.74 billion units. (If you want to be very precise, Gartner estimates that 2,738,366 machines were sold in the second quarter of this year.) The top five shippers were Dell (19.3 percent), HPE (17.3 percent), Lenovo (8.6 percent), Huawei Technologies (5.1 percent), and Inspur (4.4 percent). Dell had a very good quarter in terms of shipments and for the first time since Hewlett Packard bought Compaq a decade and a half ago, Dell is the number one X86 server shipper (and therefore the number one server shipper overall) after growing its boxes sold by 8.9 percent in the quarter. HPE stomached an 18.6 percent shipment decline in the X86 server space, some of which was due to its spinoff off its Chinese server business to HC3 (which is has a stake in with partner Tsinghua) and some of which was due to difficulties in selling in China. Dell had its own issues in the quarter on the server revenue front, which it openly admitted as the EMC acquisition was being done last week, including softness in China and among enterprise customers in general. (Both HPE and Dell have fiscal quarters that extend beyond the calendar quarters, so mapping their financials to the calendar quarters is not easy.)

At this point, X86 iron represents 99.3 percent of worldwide server shipments based on the Gartner data and 86.6 percent of revenues. For those of you who are students of data processing history, this is just an astounding level of market share. Intel has a tremendous amount of power in the datacenter, and as it solidifies its position in storage and expands aggressively into networking, this will grow. But unless and until Unix systems and mainframes are unplugged in datacenters, it will be hard for Intel Xeons to grow revenue market share. And the vast profits that Intel extracts from Xeons – we are talking 50 percent gross margins for its Data Center Group – make it a target of every processing wannabe in the world. Markets do not let vendors have this kind of control for long. Just ask IBM. But Intel is smarter than IBM, and its paranoia about competition has served it well and helped it preserve and extend its position in the datacenter.

There are those who are hoping for a resurgence if the Power architecture and the emergence of ARM in servers to bring about a revival in RISC systems competition for the Xeon platform, not to mention a little competition from AMD’s “Zen” Opterons due next year. The ARM segment is mostly tire kickers still and if there were 10,000 server units shipped in 2015 based on ARM chips, we would be surprised. (We think it will double this year, and maybe quadruple next year as machines go into production.)

But until then, the RISC/Itanium market is in perpetual decline. In the second quarter, Gartner reckons that a mere 16,873 such machines shipped, down 15.5 percent year-on-year. Oracle was the top shipper in the quarter, not Big Blue, because it had a much more muted decline in shipments (down 4.9 percent to just over 8,000 units) compared to IBM (down 30.5 percent to 5,681 units). With the H3C spinoff, HPE’s Itanium system shipment were off by 32.9 percent, to 1,678 machines; H3C pushed 483 Superdome-class machines. Even if HPE had not sold off its China Superdome business to H3C, it would have been down. (And incidentally, even with the H3C spinoff of X86-based servers being added back into HPE’s numbers for the second quarter, Dell would have beaten HPE as the top X86 server shipper in the world.)

As for revenues, the Unix operating system running on RISC/Itanium machinery totaled $872.2 million, down 20.7 percent. IBM had 48.9 percent share at $426.9 million in revenues, but was down 30.4 percent as the Power8 chip comes to the end of its cycle excepting the new NVLink-capable machines and some revamped two-socket servers for Linux made by Supermicro announced last week. Oracle was down 9.6 percent with its Sparc systems, to $263.1 million. Interestingly, HPE’s Unix system revenues fell by 24.2 percent in Q2 to $100.8 million, but the majority of that decline was the shift of $23.7 million in sales that it would have booked in China had it not given that business to H3C as part of its partnership with Tsinghua. Fujitsu had a decent shipment bump in its Sparc64 line, but revenues still dropped by 121 percent to $26.1 million. You can see now why Fujitsu is spending several hundred million dollars developing its own ARM processor – it wants to surf up the ARM wave when it comes and also participate in a broader Linux ecosystem.

If you look at other systems – mainframes from IBM, Unisys, Bull, NEC, and Hitachi plus proprietary minis such as IBM’s Power-based systems running IBM i (formerly known as the AS/400), these machines accounted for around 2,300 shipments in total in the quarter, up 41 percent, but revenues were down 35.5 percent to $945.9 million. Both Unix and Others dropped below $1 billion in sales for the first time.

When all is said and done, vendors are in the server racket to make money, something that is increasingly difficult when they bear the cost of system engineering and Intel, Microsoft, and Red Hat collectively get most of the profits. There is without question more margin in the operating system than in the hardware these days, and middleware and databases have even more profits.

This is why Oracle persists in its plan to create engineered systems. It can indulge in hardware because it is already pulling a lot of profit from systems software. What Oracle wants to do is control its stack, absolutely, and gain advantages in increased performance and lower support costs that then feed back into growing its engineered systems business. In essence, Oracle really does want to recreate the IBM mainframe experience on a cluster. If Dell gets its own operating system act together and makes Photon a real Linux distro, with VMware and Cloud Foundry it would also be able to control its own platform (minus the processor, unlike Oracle with the Sparc chip). Even when Oracle can’t control the processor, as with Exa line of database, middleware, and analytics systems, it can control everything else. Few others can do this – except hyperscalers and cloud builders, which are maniacal about controlling their stacks. HPE, which is selling off its software business, is moving in the opposite direction, which seems peculiar but like IBM in the 1990s with its software, HPE wants its hardware to be the neutral choice and be embraced enthusiastically by software makers.

The figures above do not reflect the software component of systems, and it would be fascinating to bring them both together to see how systems really stack up.

In any event, despite the challenges, HPE is still the dominant revenue producer in the server business, at $3.21 billion in revenues in the second quarter, despite a 6.4 percent dip. (We think a lot of that came through the spinoff of its server business in China to H3C, but some of it was a softening in ProLiant server sales, particularly to SMB customers. Dell, thanks largely to hyperscale and cloud deals and despite a softening of its own in sales in China and to enterprises, had a 9.9 percent revenue jump to $2.59 billion. If these trends persist, Dell will be the shipment and revenue leader in the server market worldwide for the first time in its history within a year or so. This is a position it has coveted, but one that might come just as the whole market starts shifting to more complex architectures tuned for specific work. Whole chunks of the SMB sector might move to the cloud, and high end enterprises might start doing very funky things indeed as more options for compute come into the field.

What seems clear is that IBM needs to pump up the Power business a lot more. In the quarter, overall server sales were down 34.4 percent to $1.23 billion. IBM is not filling in the gap – not even close – left by its sale of the System x division to Lenovo two years ago. Lenovo seems to have stabilized its server business, which is comprised mostly from that IBM unit, with sales up 1.9 percent to $968.2 billion. Cisco Systems, which upset the enterprise server applecart back in 2009 with the launch of its Unified Computing Systems converged systems has peaked with the number five position in the market. This is remarkable, and $858.9 million in sales (down nearly a point) is nothing to be ashamed of.

The truly remarkable thing is that the market for servers continues to be diverse. Other vendors outside of the Top 5 players continue to grow, and as a group their revenues in Q2 grew by 12.3 percent to $4.7 billion. They accounted for more than 50 percent of server shipments and just under 35 percent of revenues in the second quarter.

The Second Opinion From IDC

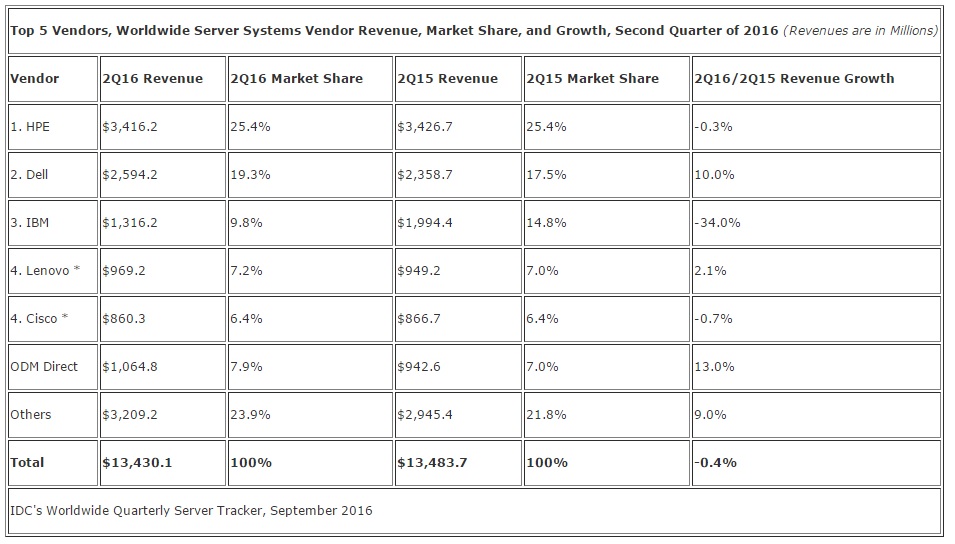

Just after we went to press with this story, IDC put out its numbers for the second quarter for the server market. As we pointed out above, Gartner and IDC look at the market a little differently, and in this quarter they don’t precisely agree on what is going on out there.

In Q2, IDC believes that the world’s server makers pushed only 2.4 million servers out of their factories, a 2.6 percent increase from the year-ago period. It is significant that enterprise spending on servers has softened a bit and the hyperscalers have hit a bit of a lull as far as IDC can see. So the way IDC counts sales out of the factory (not revenues at the retail level), it reckons that those servers generated $13.43 billion in sales down four-tenths of a point compared to the second quarter of 2015.

The volume part of the market, where machines cost under $25,000, grew revenues by 5.3 percent to $10.6 billion, and while the midrange sector, where machines cost between $25,000 and $250,000, grew by an impressive 12.7 percent, these systems only generated $1.3 billion in the aggregate. High end machines, which cost more than $250,000 and which are dominated by IBM’s mainframes and Power Systems, had a 31.4 percent decline in the quarter to $1.6 billion. If you do the math, these IBM platforms generated $1.34 billion in revenues, which is why IBM stays in the game in systems. IBM’s systems still drive lots of operating system and middleware revenues, which are annuity-like thanks to monthly licenses for this code and which are extremely sticky and difficult to replace.

Some hyperscalers and cloud builders buy from OEMs such as HPE, Dell, and Lenovo, but a bunch buy from ODMs like Quanta Computer and those that are somewhere in between like Supermicro. Even though spending by hyperscalers took a pause in Q2, sales for the ODMs started too rise again and were up above the $1 billion mark by a smidgen thanks to 9 percent revenue growth. We would love to see all hyperscale and cloud revenues by vendor, since some of the HPE, Dell, and Lenovo sales are really ODM-like in nature.

As we contemplate how fast compute is changing in the datacenter to address so many competing needs, we think new architectures will find their places over the next decade as Moore’s Law runs out of gas, and perhaps more importantly, it will be increasingly difficult to talk about a box that centralizes compute. Compute is going to everywhere, all around us, doing all kinds of processing in real-time and feeding back into the datacenter for aggregation and analysis. The real question is not how distributed clusters in a datacenter will look ten years from now, but how compute will be distributed from end points and in layers of networks before data is even shipped back into the datacenter for final storage and analytics. There could be as much processing outside the “server” and the “datacenter” as inside of it. These terms could become somewhat meaningless.

Given the licence cost per core of a lot of software and the requirement to licence all cores, I am surprised we have not seen fast 1 or 2 core systems that support lots of RAM. Even without licence costs having a larger cache may be of more benefit then more cores, yet Intel forces lots of cores on anyone that wants lots of RAM.

Since Virtualization is the buzz since 5-6 years now I don’t see the point of your remark. I don’t think there is simply no demand except for probably storage servers, SANs

Virtualization does not work well when you are selling software solutions that the end user’s department has paid for the software and always blames the software vendor if the system goes slow, not there IT department. Hence having a box that JUST runs one system can avoid lots of disputes.

At least virtualization removes most licence cost from cores you decide not to use.

There are chips designed for that in the E7 realm, specifically designed for the SQL market, high mhz, low core count. Oracle has plugged the hole, by insisting that any CHASSIS capable of running 4 procs (meaning capable of running E7s) cannot run oracle standard….but MS-SQL has not quite got round to plugging the same hole. Mainly because they still want to be cheaper than Oracle.