Where do you go when you are an infrastructure software provider that already has 500,000 enterprise customers? That is about as good and as big as it gets, particularly when the biggest spenders in IT infrastructure, the hyperscalers and the largest cloud builders, create their own hardware and infrastructure software and inspire legions of companies to follow their lead, often with open source projects they found.

So VMware, which has grown into a nearly $7 billion software powerhouse, has done so in the only way that any company can that has reached such a saturation point in the market. Having gone deep, it goes wide. That has meant extending its server virtualization base in the datacenter, which has focused on X86 iron and which gave X86 systems the partitioning and workload control that other, more expensive Unix and proprietary systems had for more than a decade ahead of VMware’s ESXi hypervisor. VMware bought Nicira in 2012 for $1.26 billion to get into network virtualization and it created Virtual SAN to get into storage virtualization, and has rounded out its efforts here as well as in controlling applications and clients, all through a mix of homegrown and acquired products.

VMware is hosting its annual partner and customer extravaganza this week, and it has long since outgrown the facilities in San Francisco and is hosting VMworld in Las Vegas with 23,000 people in attendance and untold tens of thousands checking in online. That is a respectable portion of its base and its 75,000 partners – can there really be that many IT companies? – showing up to an event. And while everyone is thinking about what VMware is saying about the future, particularly with the $67 billion Dell deal for EMC, and thus also for VMware, expected to close on September 7, and so much tumult in the datacenter infrastructure space, it is indeed fitting to think about the future.

Paul Maritz, the Microsoft executive who took over running VMware from co-founder Diane Greene after she was ousted, used to say that the company was building “a 21st century software mainframe,” and the stack that VMware has created comes pretty close to that technically and economically. If we have any misgivings about the Dell deal, it is simply that with Dell being private, that removed a key player in servers, storage, and networking from public scrutiny, and now EMC and VMware will be cloaked in invisibility. The number two player in servers, the number one player in storage, and the number one player in datacenter virtualization will be cloaked in invisibility, and we will be worse off for not knowing how they are doing and what they are doing with the same precision as we are used to from three separate public companies. We will get to the announcements from VMware, such as they are, in a separate story. But we may as well take a look at how VMware has done financially since the Great Recession and how it has transformed itself to prepare for a future that is much more complex than the one it took on when it started virtualizing X86 servers in earnest just before that recession hit and made its products vital to enterprises the world over. It made IT managers into heroes, and you don’t see that very often.

What Great Recession?

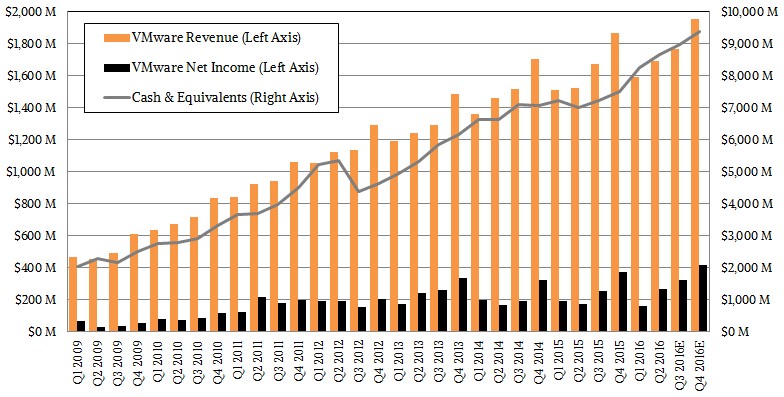

While those peddling physical servers took it very hard on the chin when the Great Recession started, but VMware’s revenues and profits grew because the ESXi hypervisor and the vSphere management tools for it were mature enough to help companies stave off having to do server upgrades for a year or more as they used virtualization to consolidate workloads and drive up utilization. Spending on the VMware software, which was not cheap by any means, allowed them to not only put off buying new iron, but allowed them to have more flexible and resilient infrastructure to boot.

When the global economy picked up, virtualizing servers became the norm, and even with intense competition from Microsoft with Hyper-V and Red Hat and others with KVM, VMware was able to keep growing revenues and profits, although it did hit a few bumps in 2012 just as it spent that big wad of cash for Nicira. Net income flattened out even as revenues were growing, and there was a tough patch in 2015, too, as you can see in the chart above.

What is not so obvious in the chart above is how fast VMware revenue growth has been decelerating even as it has been growing. (This is why we build charts with long time horizons.) In 2010, when the Great Recession was backing off and most of the major economies were starting to recover, VMware had 41.2 percent revenue growth and 81.4 percent net income growth, and in 2011, even though revenue growth had shrunk to 31.8 percent, net income more than doubled. In 2012, when the market tightened and competition really kicked in for server virtualization and the first rumblings of commercial-grade containerization were being felt, VMware’s revenue growth fell to 22.2 percent and net income only rose by 3 percent. In 2013, growth slipped further to 13 percent, but cost cutting and careful management got profits growing at nearly three times that rate. So the arrows were pointing in the right direction, and with the magnitude between revenue and profit growth being what you expect from a company with a vast installed base selling a legacy product that datacenters are addicted to. (Just like a real mainframe, which is more than five decades old.) In 2014, revenue growth picked up a few points, but net income fell by 12.5 percent, and last year revenues at VMware only grew by 8.9 percent and profits by only 12.5 percent.

The good news is that VMware is bringing somewhere between 15 percent and 20 percent of its sales to the bottom line, depending on the quarter, and based on what it has told Wall Street when going over its figures for the second quarter, it will probably break $7 billion in revenues and have something on the order of $9.4 billion in cash in the bank.

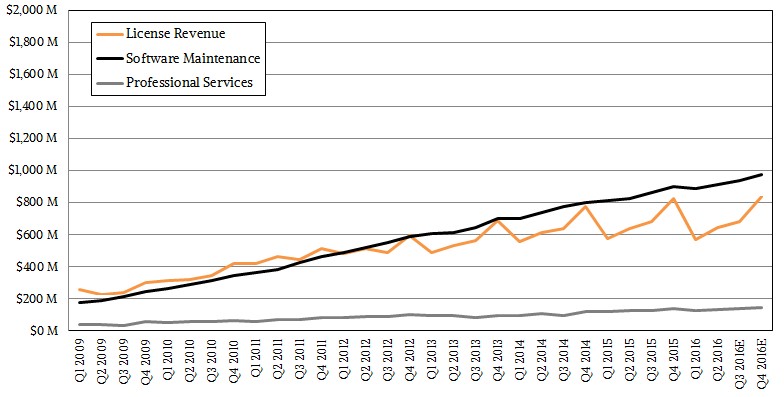

What is going on here? Well, VMware has 500,000 customers with millions of its hypervisors installed running perhaps 50 million to 60 million virtual machines. But it has had 500,000 customers for quite a few years, and it probably will not ever have 1 million customers. This chart shows that is going on pretty well:

What is clear is that VMware is seeing something that looks like a more traditional enterprise server upgrade cycle, with peaks in the fourth quarter and valleys in the first quarter, which is no surprise since the company has been focusing on enterprise license agreements with big customers for many years. (Be careful about wanting to be a mainframe wannabe.) As you can see, the license revenues for VMware have been choppier, yet fairly predictable, in recent years, but the software maintenance stream from that installed base is steady and straight as an arrow. This is, again, very similar to the cycle that IBM sees with its mainframes, with monthly rentals on software and an S curve upgrade cycle on mainframe hardware. Professional services is an important business for VMware, but only for the largest accounts. VMware has made a conscious decision to not compete with its partners on most professional services engagements. That is why the growth is much slower and the revenue much lower here.

Changing these curves and riding the waves of change with cloud computing (including OpenStack as well as its own vCloud) and other forms of virtualization (including containers) is why VMware CEO Pat Gelsinger changed up the management team earlier this year and why former president and chief operating officer Carl Eschenbach is now working with the company in an advisory role and is not the heir apparent at the virtualization giant.

The NSX network virtualization and Virtual SAN hyperconverged storage products that VMware has been building out and building up for the past several years are growing, but they have not taken the market by storm like the ESXi hypervisor did during the Great Recession. NSX now has 1,700 customers and VSAN has over 5,000 customers as the second quarter came to a close in June (the latter up from 3,500 in the first quarter). VSAN plus VxRAIL hyperconverged system sales together more than tripled, with VxRail being helped by hardware agreements with EMC and Dell (ironically, har har.) But management software bookings in the second quarter were up in the single digits and licenses for compute products – meaning ESXi and vSphere for server virtualization proper – declined by the low single digits. Bookings for licenses and software maintenance for the compute products is still growing in the low single digits and for the management products is still growing in the low double digits.

In other words, this is still a great business, and VMware has plenty of cash, technical skill, and maneuvering room to create products for the next wave of computing, which will include much more orchestration and automation and very likely a containerized environment not running on a server virtualization substrate.

The real wildcard in all of this is happens to be what Michael Dell intends to do with VMware and EMC and how that will be reconciled with the strong partnerships that Dell has with both Microsoft and Red Hat. Dell, the man, may decide to try to sell anything and everything, or he may decide to rationalize and focus the VMware and EMC products and take on Microsoft, Red Hat, Nutanix, and others at the core infrastructure software layer. The thing to remember is that VMware was a much smaller company on the other side of the Great Recession, and it innovated and adapted to quadruple sales over that time.

It is hard to see how Dell could ramp up VMware’s volumes, since VMware has more enterprise customers than Dell does. Maybe Dell will give special deals on servers to those who buy VMware software? It would not be the first time such a deal was given to enterprise customers. Dell has lots of options – it could turn out to be too many, or just enough. Time will tell.

Thank you for this very insightful article. My understanding is that VMware is to remain a publicly traded company after the Dell transaction closes. Dell is taking EMC private but not VMware. This seems to differ from your comments about VMware going invisible?