The voracious appetite for compute and storage capacity among hyperscalers and cloud builders once again drove the server market to new heights as 2015 came to a close, and unless some wobbling from Hewlett Packard Enteprise and Cisco Systems is a leading indicator of a slowdown – and we do not think it is – then this year will probably also be a record setter.

To a certain extent, it is a tale of four server markets, and the hyperscalers and cloud builders are increasingly setting the pace even as enterprise customers still account for the bulk of sales of both volume X86 machinery and other gear like RISC/Unix and mainframe systems that are still the popular foundations of ERP systems and the databases that back them. And then, of course, there are high performance computing clusters that run the world’s simulation and modeling applications. There is some blurring between these lines, of course, which is one of the things that The Next Platform chronicles.

The two big market researchers that do the quarterly box counting in the server business, IDC and Gartner, track the business is slightly different ways, with IDC looking at sales at the factory level coming out of manufacturers and Gartner measuring the flow after machines go through the channel and as they are moved into corporate datacenters. Both provide an insight into different market dynamics, presenting a fuller picture of what is going on.

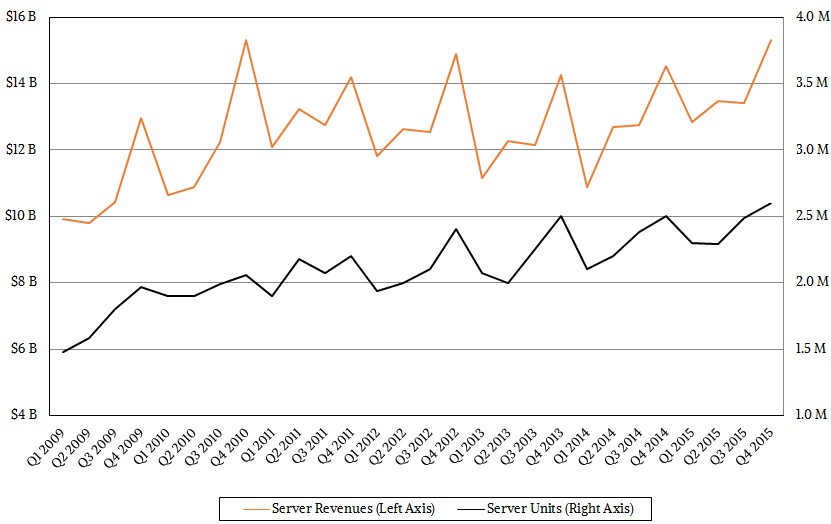

According to IDC, the world consumed 2.6 million servers in the fourth quarter of 2015, an increase of 3.8 percent compared to the final quarter of 2014; those machines drove $15.31 billion in revenues, a 5.2 percent bump over that year. For the full 2015 year, server revenues rose 8 percent to $55.1 billion and shipments were up 4.9 percent to 9.7 million machines.

As you can see from the chart above, the revenue levels set in the fourth quarter of last year matched the previous high at the end of 2010, when server revenues came roaring back in the wake of a two-year drought during the Great Recession. It took 30 percent more server units to drive that same revenue level, however. Both server revenues and shipments rise and fall depending on the quarter, but the general trend is for shipments, which are overwhelmingly comprised of X86 machinery, to rise more or less linearly. After the post-recession bump in 2010, server revenues had been trending downwards as the RISC/Unix and Itanium markets declined, but the uptake of richer configurations of X86 iron in recent years is helping reverse the revenue decline if the 2014 and 2015 numbers are any indication. We shall see what 2016 holds.

Thanks to Moore’s Law in general and the need by hyperscalers and cloud builders to beat – not just meet – Moore’s Law improvements in their minimalist system designs and cost-cutting, the industry is making it up in volume. We suspect, however, that profits are down across all classes and types of servers, and that is just the way it is here on Earth.

Not only did the hyperscalers and cloud builders account for a big share of sales and an even larger portion of the growth in the market, but companies in China spent like crazy on servers. Revenues for servers in China were up 15.6 percent to $2.3 billion, according to IDC. The top four OEM server makers – Inspur, Huawei Technologies, Lenovo, and Sugon saw a combined growth rate of 19.5 percent. Despite all of the economic uncertainty in the Middle Kingdom, companies and government agencies are clearly investing in platforms. Across all of Asia/Pacific and Japan, server revenues rose 14.7 percent, which was a lot more ebullient than in the United States, which only saw 7.9 percent growth; Europe, the Middle East, and Africa had even more muted revenue growth at 5 percent, a tiny bit slower than the market overall.

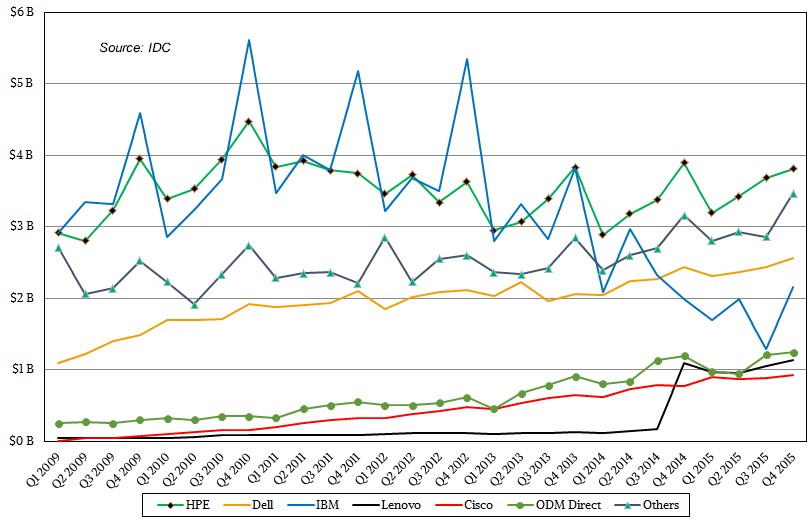

It will take a very long time for any of these vendors to catch up to the big tier one players like Hewlett-Packard Enterprise and Dell, but Lenovo and Inspur are unabashedly setting their sights on the number three position and they have a good chance of knocking IBM off its position over the long haul unless the Power Systems platforms take off as the OpenPower Foundation partners hope. (And so long as ARM processors remain a minor part of the market as they are now.)

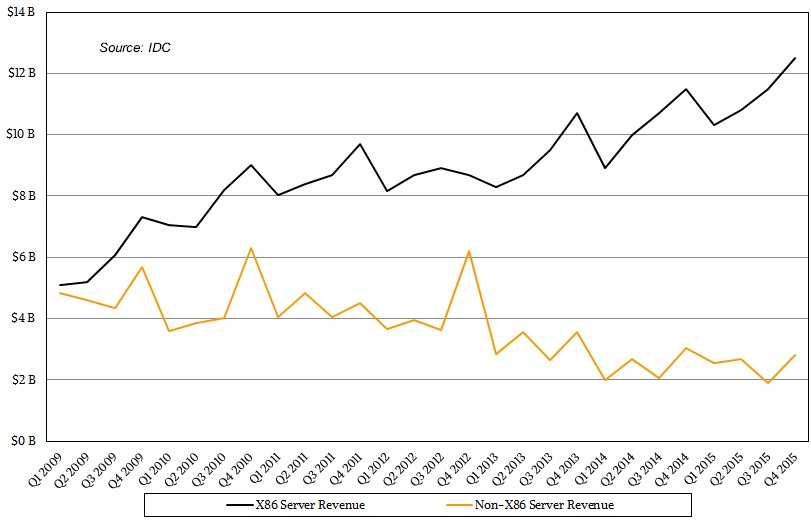

The server market has changed dramatically since the Great Recession, and in fact, we contend that it was that very recession that changed the dynamics of this business. The drive to higher efficiency and lower cost has all but driven non-X86 servers from the market except in use cases where high I/O bandwidth or shared memory capacity warrant something other than a two-socket machine. Looking ahead ten more years and perhaps after one more recession, it is hard to imagine these machines, we truly love for their power, ease of programming, and elegance, surviving except in the most extenuating of circumstances. By then, maybe ARM servers will come in to keep it interesting.

In the meantime, IBM saw its revenues of Power Systems and System z mainframes rise to $2.56 billion, the first quarter where the hangover from the sale of the System x X86 server business to Lenovo did not affect its results. IBM is now generating less than half of the revenues it did coming out of the Great Recession in 2010, when it had three server lines, and it is fairly safe to bet that IBM will never be the number one maker of servers again. It may, however, still be the most profitable maker of servers, and that is something that Big Blue has always focused on.

There are some interesting lines to watch in that vendor chart above. First, look at the rose of the Original Design Manufacturers (ODMs) who help design and make machines for the hyperscalers and cloud builders who have long since stopped buying off-the-shelf gear from the tier one suppliers. The other interesting numbers to watch are for Dell, which has increased its sales by a factor of 2.5X since the recession began, and Cisco Systems, which launched its Unified Computing System blade servers into the gaping maw of that recession and started the converged infrastructure revolution.

Hewlett-Packard has been struggling to maintain through all of its system transitions, and to its credit it has done a pretty good job as its AlphaServer, Tandem, and Itanium server businesses collapsed. In the fourth quarter of last year, Gartner said in its report that HPE’s big problem was that shipments of Windows-based servers declined and its Unix server business was also off, as expected.

Lenovo will find its footing and turn around that System x business, much as it did with IBM’s PC business a decade ago and its trendline is beginning to show that.

Perhaps the most encouraging thing in the IDC data is the growth of other vendors in the market, who were flat-lining a bit ahead of and during the recession. In this other category are niche players like Cray, which is anything but a niche in its high performance computing market and which is getting more and more traction selling clustered systems into the enterprise.

The big trend – and one that we have not seen any data on but that we suspect is well under way – is small and some medium businesses abandoning their dataclosets and baby datacenters to move their applications to the cloud, either literally or by shifting to software services running on clouds. It came as no shock to us at all when Jason Waxman, general manager of the Cloud Platforms Group at Intel, said this week that by 2025, Intel expects that 70 percent to 80 percent of all servers shipped will be deployed in large scale data centers. Waxman qualified that further by saying a large scale datacenter was one with thousands of systems and engaged in infrastructure, platform, or software services, including the big cloud providers as well as smaller players and service providers and telcos that compete against them. If we are indeed going to have a recession in 2017 or 2018, as some economists expect, this will accelerate this and other transitions, and it will be interesting in that this will also be about the time that several new processing and storage technologies will be coming to market.

But looking far out into the future, infrastructure will probably be something that only experts do. Just like with electricity generation and distribution, which was something every company did for itself for many years until it was consolidated. A market and governments won’t tolerate massive consolidation, but they will accept two or three big players and a few smaller niche players. Given the investments necessary to become a global scale cloud provider, it is hard to imagine that Google, Amazon, and Microsoft won’t be the dominant players in 2025. Unless, of course, Facebook decides to sell infrastructure. That would be fun indeed.

Gartner and IDC server unit shipment data has always been meaningless, because both fail to address what is a server, and how many of them are in a system.

To some degree this lack of meaning is designed to disguise the actual volumes of Xeon processors produced in any architectural cycle. That also masks DCG’s revenue and the extent DCG subsidizes other Intel divisions.

A meaningful assessment looks at the number of processors, cores or threads, instances of compute. The number of TRS ports is much more meaningful.

Mike Bruzzone, Camp Marketing