The results of the Top 500 list of the world’s fastest supercomputers has just been announced, and while there are no big surprises at the top outside of a couple of new additions, the real news sits farther down the stack—and could speak volumes about the global supercomputing race in terms of which countries are pushing investments.

There is no question that once again, China is taking center stage. Between this morning’s announcement of the Top 500 and the earlier list this summer, just four months ago, China has almost tripled the number of supercomputers on the global list. The story goes far beyond the most famous machine on the global stage. As expected, for the third year in a row, the Tianhe-2 supercomputer at the National University of Defense Technology (NUDT) has topped the list with over 33 petaflops of peak performance. While this won’t last forever since the planned upgrade of that machine will be delayed due to the embargo on Intel chips, the bigger story on the bi-annual rankings of the largest, fastest systems on the planet is not about that supercomputer, but the fact that China is pumping its presence across the list overall.

On the one hand, this is not a new trend. Over the summer, we reported at length on the dramatic moves China has made to bolster its supercomputing presence, in addition to how the nation is bolstering efforts to develop native architectures for next-generation supercomputers, including DSPs, to circumvent restrictions against their use of Intel chips for its largest system (and a few others that are deemed concerns from a national security perspective).

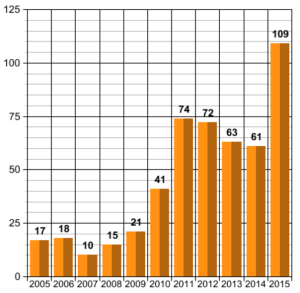

Between July, 2015 (when the first rankings were announced this year) and now, there has been a staggering 3X growth in the number of machines from across China. To put that in global context, since the ranking over the summer, the number of top-tier supercomputers in the U.S. dropped from 231 to 201 and represents the fewest U.S. systems on the list since the rankings began over twenty years ago. The dropping systems trend is echoed in Europe, which had 141 machines on the summer list and now has 107. Japan’s numbers dropped by four machines, but overall, China now has 109 systems—a trend worth paying attention to.

From the casual observer’s perspective, this might imply that China is simply in a race to dominate the global supercomputing space with the most (and the most powerful systems). While high performance computing (HPC) is, indeed, a core part of the technology and scientific investment strategy in China, things are, as usual, not so black and white. Indeed, Chinese vendors are making a broad push for recognition in their homeland, which has been dominated by vendors like IBM, Dell, HP, and others, but the dramatic refactoring of the Top 500 list in China’s favor isn’t as simple as it seems.

For instance, even though the system counts are falling at unprecedented rates in the United States and to a slightly lesser extent, in Europe, loser inspection reveals that there are many machines from elsewhere around the world on the existing list that are between two and three years old, which means those upgrades are on the horizon. One can expect that there are currently several centers waiting on new technologies, including OmniPath, Knights Landing, and Broadwell—all of which are tentatively expected to hit general availability sometime in the first quarter to first half of 2016.

In short, by the summer list (assuming product roadmaps deliver as anticipated and systems can be validated before the LINPACK benchmark), one can expect to see a fresh new crop of machines from around the world, but with particular emphasis in the U.S. and Europe, where we already know some major contracts for big research and commercial HPC systems have been inked and are waiting on parts. But this doesn’t change the fact that China has added some fresh numbers to the list to make smaller machines vie harder.

And speaking of that lower tier of the list, it’s worth noting it is there where many of the new machines lie. Where do they come from and what do they do?

For starters, Chinese systems vendor, Sugon, has now overtaken IBM on the Top 500. And for that fresh crop of new machines consider that Sugon alone went from five machines on the Top 500 in summer yet now has a total of 50. The company’s five big notable systems that ran the Top 500 LINPACK benchmark for the summer list were all major research and scientific centers in China. Sugon’s largest site, the National Supercomputing Centre in Shenzen with its 2.9 petaflop Nebulae machine (#48) and the other machines, which take the #95, #236, #352, and #436 spots are all still present but this November’s massive enrichment of those numbers is not coming from academia and research. But a careful look at the fifty listings reveals that most of the new entries are toward the bottom of the list, many are clustered together and feature very similar architectures, and almost all of them are for telecommunications and internet, with a smattering also dedicated to government. In other words, in an effort to concentrate attention to the health of their business—and possibly to show HP, Dell, and others that China is serious about wanting to keep its technology as domestic as possible (even if for now it still relies on U.S. based processors—only the large nuclear research sites are part of the embargo), Sugon convinced existing and new webscale customers to run LINPACK.

To put this into the context of the Top 500 list, there are certainly entries that fall under the telco and internet sector, but the list is heavily centered around government and research with other prominent industries being oil and gas, financial services, and manufacturing, among a few others. But counting internet and telco clusters on the Top 500? It’s not the norm—but it’s still feasible, not to mention a great way to flood the list, whether inadvertently or not.

Sugon takes top billing for the vendor that came out of the woodwork (to some extent, they’ve been a presence in HPC for some time) but other vendors in China are having quite a showing as well. For instance, Inspur, the integrator for the top system on the planet, Tianhe-2, had just one machine on the list in summer and now boasts 15. And Lenovo is also on the grow, although recall that they acquired IBM’s X86 business last year (and there are still BlueGene based architectures that are dropping off the list). And Lenovo, another Chinese company, is pushing ahead as well, moving from just three systems on the last rankings to 25 on the current rankings.

What we have on this list is a “qualified” note about China’s potential, aims, and realities as far as supercomputing prowess in the year to come. On the one hand, there is no denying that there are stepped up efforts to make it clear that they intend to dominate in both system and performance share of the Top 500. Further, we are seeing a great deal of that force shining through as a result of China’s Sugon, which added significantly to China’s Top 500 supercomputer bottom line.

However, it is with equal weight that we add a “wait and see” given what the following year will bring. New processor, interconnect, and large-scale system installations elsewhere in the world will re-tip the new balance China has struck, which means that indeed, as we predicted this summer, 2016 will be the year that HPC becomes quite lively indeed. Not just in terms of geographical trends, but on the hardware, software, and application ends. More on that in our detailed analysis published this morning of the November 2015 Top 500 results.

So what happened to the “shrinking funding” reported back in September?

There was an interesting slide at HPC China 2015 just last week, where top machines in China were listed

At the bottom of the slide, it said “unfortunately our 100 petaflop machine was not able to make it on the list this year”

Next June will be interesting indeed, although it might not be the way some are hoping.