There are many vectors to scale, and we try to examine them all here at The Next Platform as we consider the implications for the systems, storage, and switching that IT organizations buy or rent to support their applications.

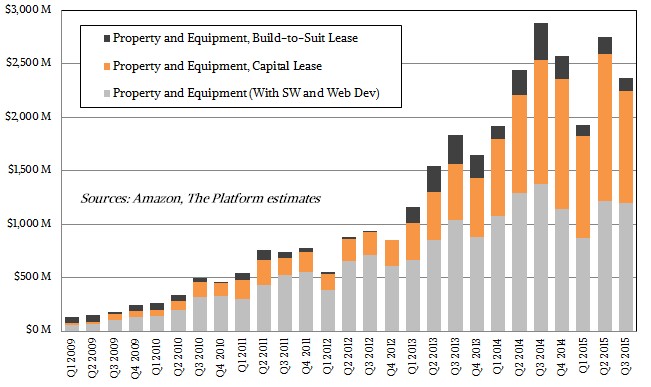

One aspect of scale – and perhaps the most important one for the long term of platform architectures – has nothing to do with bits or flops, but is money and its effect on the economies of scale it can buy and the virtuous cycle, as Amazon Web Services calls it, that hyperscaling provides to those who do it. Time does, in fact, equal money, as we all know, and many of the companies that are trying to build public clouds do not seem to understand that if you didn’t start building your cloud a long time ago, you have to spend a ridiculous amount of money to catch up and then wait and quite possibly lose money as you attract enough customers to hit a critical mass. These are very big bets, and the payoff is far from certain.

This is made quite clear on a day when Amazon is reporting exploding growth for its public cloud and seems to be widening the gap with its peers –just one day after Hewlett-Packard announced that it would be shutting down its Helion OpenStack-based public cloud.

If HP and Dell, who are the two largest server makers in the world, who just so happen to have their own switching and storage businesses, can’t make a public cloud to compete against Amazon Web Services, Google Cloud Platform, and Microsoft Azure, why do they think that over the long haul they will be able to provide private clouds to enterprises who, at least for the moment, want to operate in a hybrid mode? Is hybrid cloud a stepping stone to the public cloud? In theory, it might be, but over the long haul, the economics might compel just about every organization to give up on their own datacenters. That is certainly the view of one HPC luminary who helped Netflix ditch its own datacenters for virtual resources running on AWS.

If the economics will determine who has the most expansive and rich public cloud, then the market will only have room for a few players when all of the dust settles. And that could be a mere few big players, each of whom will have far more sway over the IT operations of the corporations, governments, and other institutions of the world than IBM, back in the 1960s and 1970s, and Microsoft, in the 1980s and 1990s, ever had. The breadth and depth of services that AWS has is astounding, and we can forgive companies like HP and Dell for thinking they could build their own clouds with their own infrastructure and lay down a basic substrate on which partners could provide higher-level software.

But it is not that simple, as both companies found out and as IBM, which bought SoftLayer in June 2013 for $2.2 billion and has subsequently pumped at least another $1.2 billion into it since, may soon learn. While SoftLayer has well over 30,000 customers and 28 datacenters with the capacity to house more than 335,000 servers (we think these centers might be around half full, but IBM does not disclose SoftLayer’s server count), that server fleet is utterly dwarfed by that of AWS, Microsoft, and Google, who are all said to have in excess of 1 million machines. IBM is doing a lot of the right things with SoftLayer, but just as is the case with Dell and HP, that is not necessarily a guarantee of success because scale matters – and so does having that scale a long time ago as measured in computer years.

Seeing the rise of AWS at the same time that it was building bespoke systems for hyperscalers, Dell had aspirations of being a global player in the wake of its $3.9 billion acquisition of Perot Systems in September 2009. While experience in hosting and application outsourcing is important – Rackspace Hosting, SoftLayer, and others attest to this, and so did the vast hosting businesses of HP (which acquired EDS) and IBM. Dell spent years investing heavily in its own cloud, but by May 2013 the company decided to shut down its Dell Cloud, which was based on the OpenStack cloud controller and presumably Dell’s own hyperscale machinery.

HP has taken two runs at a public cloud, first with the HP Cloud and then second with HP Helion, and in the second case it, too, chose OpenStack as the software platform on which to build that public cloud. HP never talked explicitly about what kind of servers and storage it used in the Helion cloud, but the word on the street is that HP has over 300 PB of customer data in the Swift object storage that backs Helion, and that data is going to be a very difficult thing for HP to help customers to move to its chosen public clouds once Helion is shut down in January next year.

Those chosen partners are Amazon Web Services and Microsoft Azure, which do not use OpenStack and which have their own proprietary software stacks for providing infrastructure and platform cloud services. It may seem like Rackspace, as the largest cloud provider that is based on OpenStack and one of the co-founders, along with NASA, would be the obvious place for HP to suggest that customers move their workloads and data. But for whatever reason, that is not what happened. (It is a wonder why HP didn’t try to sell Helion to Rackspace, and perhaps it did try to do that.)

Both HP and Dell, like other providers of IT gear, are doubling down on hybrid cloud, with the idea that they can build private clouds that are more or less compatible with AWS and Azure inside corporate datacenters and help companies bridge that gap between public and private.

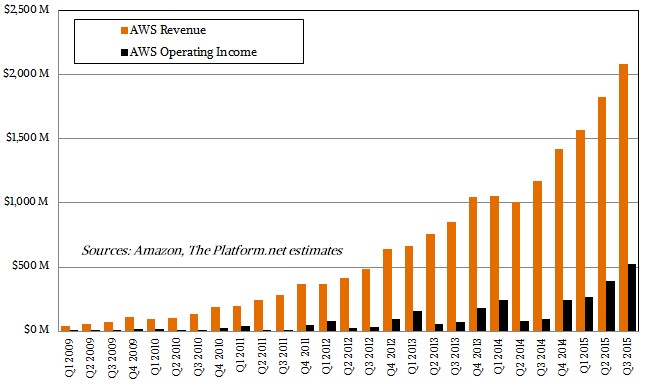

What people keep saying over and over again this week is that the public cloud business is cut-throat and low-margin, and that is why HP has to shut down Helion, and that is why Dell did, too. Amazon’s financial results do not exactly bear this out. AWS has higher operating income than Cisco Systems did in its most recent quarter (25 percent of revenues for AWS compared to 22.4 percent for Cisco). This shows the effect of being a first mover as well as being an aggressive innovator that constantly re-invests in the business to expand not only capacity, but features and functions. You have to scale on all vectors. Slapping together OpenStack on some cheap iron is just table stakes; it is the experience and the long-term viability of the supplier that companies are buying. It used to be: Nobody ever got fired for buying IBM. Now it is: Nobody will get fired for deploying on AWS.

In the third quarter ended in September, AWS brought in just under $2.1 billion in revenues, up 78 percent from its $1.17 billion in sales, and its operating income was up by a factor of 5.3X to $521 million. That gives AWS a 25 percent operating margin in the quarter, which is a significant margin expansion. To give you a sense of perspective, Amazon’s North American retail operations had just a tad bit over $15 billion in sales, up 28 percent, and that business posted a $528 million operating income, which was a lot better than the $60 million operating loss it had. The larger point is that AWS is one-seventh the size of the North American retail business at Amazon, and is generating comparable profits. (Interestingly, AWS has a positive foreign exchange bump in the quarter to the tune of $78 million, which is a neat trick given how the US-based IT suppliers who sell a lot of gear overseas are tacking a serious haircut every quarter.)

“We are continuing to see great acceleration in the pace of innovation,” explained Brian Olsavsky, chief financial officer at Amazon, citing the 530 new significant features that the company has rolled out so far this year. “The customers are really responding. They like the speed and agility that AWS provides them, and they like the new features that we launch, many of which also enable them to lower their costs.” As an example, Olsavsky cited the Aurora MySQL database service, which has five times the oomph of MySQL and costs one-tenth as much as an on-premises relational database, by Amazon’s math. :It is early days, and we enjoy a lead in this business and customers responded well, and we believe we are adding new services and features at a rate that is faster than many others. The growth rates and margins will remain lumpy and bumpy as we go forward. But we are very encouraged about the business.”

No kidding. If it were possible to just invest in AWS, as opposed to Amazon as a whole, that would probably be a good bet.

By the way, Olsavsky said that the Aurora database service has now outpaced Redshift, its data warehousing service, in terms of its explosive growth. What that tells you is that AWS is addressing cost and scalability issues with traditional relational databases and data warehouses that customers do not think they can do internally. This is not exotic Hadoop or NoSQL data store services we are talking about here.

Which brings us to the next and important point. Integrating piece part components and creating virtualized servers, storage, and networking with sophisticated orchestration and automation for customers – in other words, building private clouds – is a business, and people are buying this stuff. No question about it. But HP will need the same kind of scale across all those private clouds as it needed in the Helion Cloud to compete with AWS and keep workloads inside the corporate firewall where it can make some money. And how is that going to happen? Why will companies pay HP, Dell, IBM, or anyone else a private cloud premium? If that gap gets too big – particularly if there is an economic slowdown – then workloads will migrate en masse to the largest, safest, and most functionally rich clouds. This won’t be like 2008 and 2009 during the Great Recession, when AWS was still new and its services stack still relatively thin. Amazon Web Services, Google Compute Platform, and Microsoft Azure are platforms that can – and will – run many of the world’s workloads.

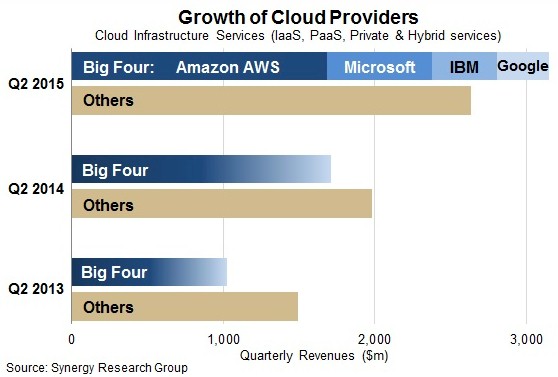

So, it is absolutely no surprise to us that HP is bowing out with Helion and that Dell did so two years ago. Others will follow suit. The revenue gap between the big four cloud providers keeps growing, as data from Synergy Research Group shows. With Amazon, Google, and IBM just reporting their financials this week, data is not out comparing cloud builders for the third quarter, but Synergy’s data from the second quarter is illustrative:

Across all types of cloud activity – infrastructure and platform services, private cloud infrastructure, and hybrid services but not including software as a service – AWS had a 29 percent share of the total cloud revenue pie in the second quarter, according to Synergy, and the top four (including Microsoft, IBM, and Google) accounted for 54 percent of revenues. The top four are, collectively, growing almost four times as fast as the rest of the cloud providers lumped together. Revenues for the cloud infrastructure were approaching $6 billion worldwide in Q2 and had a trailing twelve month run rate of nearly $20 billion.

In the end, the question is not just how many public clouds will be vaporized by the big four or five or six. But also how many of the companies that deploy private clouds that system makers build today will be doing so in five years, or ten?

Great article in summary the future looks very bleak as we tie ourselves to a few major global players who can dictate the terms and hold all of our data at the same time. I’ll bet migration will eventually become impossible too. If I were a company I would be very very careful what I buy into.