We have said it before here at The Next Platform, and we will say it again. Sometimes, it is hard to tell the difference between a server, a storage array, and a switch. Most of the market research reports that come out on a quarterly basis treat these things as distinct items, and if you add up the data for these three categories of machines, you get revenue and shipment figures that are larger than the actual market.

So you can get the wrong impression about what is going on in the glass houses and glass warehouses of the world.

To that end, the box counters at IDC started a cloud IT infrastructure counter that takes out the double counting in its wider data sets and gives a much better sense of how much infrastructure is being sold to support either private clouds or public clouds – the latter including those operating at hyperscale with applications that face consumers or businesses.

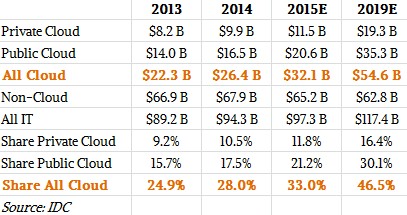

Among the more interesting bits of data to be gleaned from this converged view of the infrastructure market is the reality that while clouds are driving growth, the majority of sales are for traditional standalone or distributed systems that have not been virtualized and orchestrated to turn them into clouds. Here is what the past two years look like, as well as a forecast for 2015 and another one for 2019:

It is hard to imagine why everything won’t be cloudy by 2019, but it comes down to definitions. Plenty of organizations will deploy bare metal machines running siloed workloads like big databases behind enterprise software stacks that collect the money and pay the bills. Plenty of HPC clusters will be bare metal iron, too, because of the substantial overhead that virtualization imposes, but we think that containerization will become the norm for those who want ease of software deployment and maintenance, and in our mind, this counts as cloud. (It remains to be seen if HPC shops will go for it, but the largest hyperscalers deploy apps on containers, and they are no less obsessed about compute and network efficiency.)

What is clear in the table above is that spending on cloudy infrastructure is rising, and it is bringing up the rest of the market as far as IDC is concerned. (That does not mean there are not pockets of growth in traditional servers, storage, and switching, so be careful of reading too much into the aggregate data.) Spending on gear aimed at traditional, non-cloud setups grew 1.5 percent across all vendors in 2014 to $67.9 billion, but is forecast to fall by 4 percent in 2015 to $65.2 billion and, significantly, will drop to $62.8 billion in IDC’s far range forecast out to 2019. During this same time, cloud infrastructure (across private and public use cases) will be growing at around 20 percent, plus or minus a little depending on the year, and will more than double from $22.3 billion in 2013 to $54.6 billion by 2019. Spending on gear for public and private clouds will grow at about the same rate during this period, and public cloud spending will always be a little less than twice the private cloud spending, interestingly.

This is all very orderly and nice, and forecasts have to be because you frankly never know when something shocking will zap the global economy. But we think that some kind of economic woe is inevitable in the next decade – have we ever had a ten year period without a recession? – and that could cause a lot more companies to shift workloads to the cloud if the economics work out to be better for them. Enterprises like operating expenses over capital expenditures, right up to the point where they think they are overspending.

The big companies running on the public cloud that we talk to think they are probably overspending on Amazon Web Services in terms of raw infrastructure and management, but probably not at all compared to what it could cost to build a datacenter and staff it with operations people and hardware experts. It is unquantifiable, in a sense, because no one knows what the market for real estate and talent is until they chase it, and then the price goes up as more and more people do. If the public cloud means anything, it means sharing resources such as people and not paying the full burden alone, and if there is a shortage of talent that knows how to use the new analytics and transactional tools, then companies will of necessity be driven to the public cloud or managed private clouds.

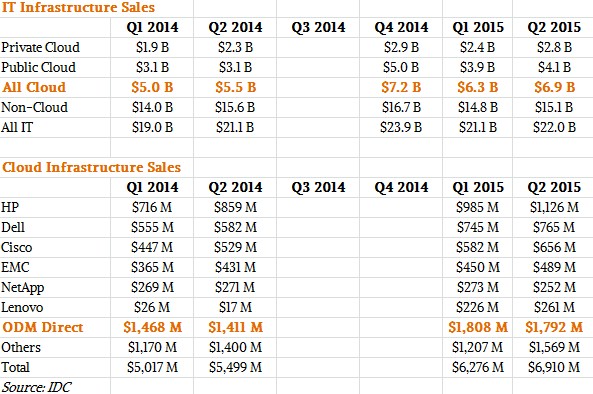

The data in the cloud IT infrastructure model that IDC has put together has only been available for the past two quarters broken out by vendor, and we will fill in this table as each quarter rolls by. Take a look:

What is interesting in this chart is that Hewlett-Packard, Dell, and Cisco Systems are the biggest vendors of systems (meaning servers, switches, and storage) that is used as a foundation for public or private clouds. And it is important to not get the wrong idea here. This data is not restricted to converged systems that combine servers and switches or hyperconverged systems that combine servers, storage, and switching, although they are part of it. It includes revenues for any vendor for any of these product categories so long as the infrastructure is aimed at clouds. (Exactly how IDC reckons hardware is being used in a cloud or not is something it has not disclosed, but we have calls in.) HP, Dell, and Cisco are also growing at 30 percent or more, faster than the cloudy infrastructure market at large, while EMC has seen its growth slow. NetApp is shrinking a bit and Lenovo is growing thanks to its acquisition of IBM’s System x business last October.

The other thing to note is that the original design manufacturers (ODMs) that sell machinery directly to hyperscaler customers like Google, Amazon, Facebook, Microsoft, and such, have not taken over the world completely, although they do have more than a quarter of the revenues for infrastructure. Considering the minimalist designs that hyperscalers insist on, it is reasonable to believe that the ODMs serving these customers have a much larger portion of server, storage, and switch shipments, but IDC has not provided such data to the public. The question we have is this: Will the ODMs get a bigger slice of the public cloud pie, or will HP, Dell, Lenovo, Cisco, and other tier one suppliers be able to take some of the share back they have lost in the past several years?

In the second quarter, the non-cloud portion of server, storage, and switching revenues combined fell by 3.5 percent to $15.1 billion, while cloud infrastructure sales rose by 25.7 percent to $6.91 billion. Interestingly, IDC says that servers, switching, and storage all showed very high growth in the quarter, with the high points being Ethernet switch sales for private clouds, up 30.1 percent, and servers for public clouds, up 36.6 percent. All three pillars of the datacenter – servers, storage, and switching – declined in the non-cloud portion of the market, says IDC.

We would love to see profit margin comparisons for cloud versus traditional. The growth might not be there for traditional servers, switches, and storage, but we have a feeling that these businesses are still profitable for those vendors who supply them. It would also be fascinating to compare the average cost of cycles, bandwidth, and bits between the cloud and traditional IT segments, and see how the ODMs compare against these broader categories. There is no doubt a wide divergence in what organizations are paying.

Be the first to comment