For certain kinds of modeling, simulation, and machine learning workloads, the advent of GPU coprocessors has been a watershed event. But as we have discussed before here at The Next Platform, there is a bit of a chicken-and-egg problem when it comes to using accelerated computing on the public cloud. The cloud builders want to know there are enough workloads that companies want to deploy using GPUs for visualization or compute before they make the substantial hardware investments that are required.

Remember, the name of the game for hyperscalers is to have as much homogeneity in their infrastructure as possible. This is why HPC-related technologies such as InfiniBand networking and GPU acceleration are not as widespread. But clearly there is enough demand for GPU acceleration for Microsoft to make a commitment to offer it on the Azure public cloud, since that is what the company did this week at its AzureCon conference.

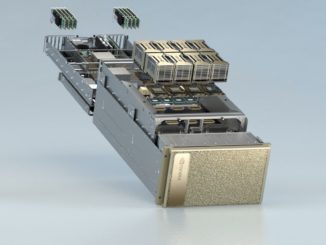

The details are a bit thin about Microsoft’s GPU plans on Azure, and it is not clear how Microsoft is integrating the Tesla K80 coprocessors, which are aimed at compute workloads, and the Tesla M60, which is aimed at visualization workloads. Both the K80 and the K60 have a pair of Nvidia GPUs on each card and are aimed at rack and tower machines. It is interesting to note that Microsoft did not choose the Tesla M6 option for the visualization workloads, which puts one “Maxwell” class GPU in a MXM mobile form factor that might have fit better into the existing Open Cloud Server infrastructure that Microsoft deploys in its datacenters. The Open Cloud Servers have a 12U high custom chassis that fits two dozen half-width two-socket Xeon E5 servers into this enclosure. Each server node has a mezzanine card that has enough room to put a single FPGA accelerator on it, as Microsoft has done for some machine learning algorithm training and network acceleration, and we would guess that the Tesla M60 could be worked to fit in there. But a Tesla K80 or Tesla K60 could not be easily plugged into this node.

If we had to guess – and we have to because Microsoft is not yet providing details about how it is integrating the Nvidia GPUs into its infrastructure but we are tracking it down – we think Microsoft is adding GPUs to its Xeon-based compute nodes by adding adjacent GPU trays that sit alongside the CPU trays in the Open Cloud Server. It is also possible that Microsoft has come up with a new server tray that puts one CPU node and one GPU accelerator on a single tray, but that would compel the company to have a different CPU node that would not necessarily be deployable for other workloads. Moreover, Microsoft might want to be able to change the ratio of CPU to GPU compute on the fly, and this could be done by means of a PCI-Express switch infrastructure. Provided the thermals and power draw works out, Microsoft could physically deploy four GPUs in a half-width tray, giving a two-to-one ratio of GPUs to CPUs in an Open Cloud Server.

Moreover, by doing it this way, Microsoft can have the same tray support Tesla K80s for compute and Tesla K60s for visualization – and perhaps even mix and match them on the same nodes to do simultaneous simulation and visualization of workloads from the Azure cloud. (Nvidia has shown off such capabilities for a few years on workstations, so why not on the clouds?)

The Tesla K80 compute accelerator is based on a pair of “Kepler” GK210 GPUs. Each of these GPUs has 2,496 cores and 12 GB of GDDR5 frame buffer memory and 240 GB/sec of memory bandwidth. These GPUs have ECC error correction on their memory – a necessary feature for compute workloads – and support a mix of single precision and double precision floating point math, unlike the Tesla K10 that is based on a pair of GK104 GPUs, which have a slightly different architecture and are aimed mostly at single-precision workloads. While many workloads use single-precision math – seismic and signal processing, video encoding and streaming, and machine learning to name a few – there are other simulation and modeling applications that require double-precision math. And that is why for public clouds, Nvidia recommends the Tesla K80s. This is another reason why Nvidia does not suggest that cloud builders use the family of GPUs based on the GRID software stack and various Kepler and Maxwell GPUs to run simulation, modeling, and machine learning workloads. By deploying Tesla K80s, the widest spectrum of workloads can be supported.

The Tesla M60 GRID coprocessors, by the way, have a pair of Maxwell-class GM204 GPUs on a card, each with 2,048 cores and 8 GB of GDDR5 memory, and the GRID 2.0 software stack adds support for the Quadro graphics drivers and the ability to virtualized the GPU and slice it up to serve many virtual CPU instances. Nvidia does not give out floating point math numbers for the GRID family of GPUs, but we presume it has a little more oomph than the Tesla K10, which is based on the prior Kepler GPUs that have 25 percent fewer CUDA cores.

It is interesting to note that Amazon Web Services does offer compute on top of its GRID-style GPUs (GRID K520s to be precise) as well as on vintage “Fermi” Tesla M2050 coprocessors which date from five years ago. IBM’s SoftLayer cloud added Tesla K80s back in July, and are another four other companies – including Nimbix, Peer1 Hosting, Penguin Computing, and Rapid Switch.

Microsoft did not provide any details on when its N family of virtual machines would be generally available using the two Tesla GPU accelerators, but Jason Zander, corporate vice president in charge of Azure infrastructure at Microsoft said they would be in preview within a few months, and that Microsoft is working with software vendors to get GPU-accelerated workloads running on the Azure cloud, presumably both Linux and Windows variants. Generally availability of the N series instances will probably be early next year. Zander did say that one of the key differentiators for the N family of Azure VMs would be the use of Remote Direct Memory Access (RDMA) over the network to reduce latency between Azure nodes, and presumably using the GPUDirect features of the Nvidia GPU accelerators, too. (Microsoft does deploy InfiniBand in some of its services, but has told The Next Platform that with the advent of RDMA over Converged Ethernet, it was focusing more on Ethernet in Azure these days.)

It will be very interesting to see how widely deployed the GPU instances are and how they are priced. SoftLayer was mum about its pricing, but Microsoft won’t be. It will also be interesting to see if Amazon Web Services upgrades its GPU compute capability, and if Google Compute Platform adds GPUs. Google has many, many thousands of GPUs that it uses internally to train its machine learning algorithms, so it knows how to integrate GPUs with its infrastructure and scale it.

Faster Azure CPU Compute

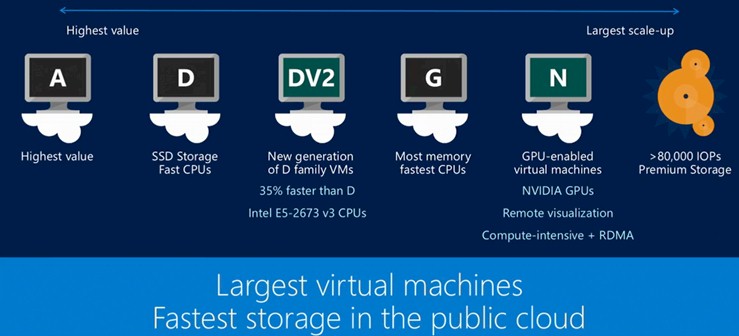

In addition to talking about the new N series GPU-backed instances, Zander also rolled out new DV2 series instances based on Intel’s “Haswell” Xeon E5 processors, which were announced last September. Specifically, the DV2 instances are based on the Xeon E5-2673 v3 processors, which appear to be a custom part with sixteen cores with a Turbo Boost speed bump to 3.2 GHz and a base clock speed of 2.4 GHz. In general, Zander said that the DV2 family of virtual machines would offer about 35 percent better performance than the D series VMs on Azure, Both the D and DV2 instances have relatively fast processors and flash-based SSDs for storage and are beefier than the entry A series, while the G series pack the most compute into an instance.

The base D1 v2 instance has a single core, 3.5 GB of memory, and 50 GB of flash for 15.5 cents per hour (about $115 per month), while the heaviest D14 v2 instance has sixteen cores, 112 GB of memory, and 800 GB of flash for $2.43 per hour (about $1,806 per month). These prices are a bit lower than what Microsoft was charging for the original D family Azure VMs, which have slower Xeon E5 processors and the same memory and storage capacities.

Starting October 1, Microsoft is reducing the prices on D series instances by 18 percent, to between 17.1 cents per hour for the D1 to $2.11 per hour for the D14 instance. That price cut makes the old D instances about 10 percent cheaper than the DV2 instances with skinnier memory and sometimes quite a bit deeper on instances with heavier memory. That means you have to do the math to figure out if you need to be on the D or DV2 instances, and it is not a simple yes or no. It depends – unless more is always better.

Be the first to comment