It has always been our contention that recessions drive successive waves of technology transitions in the datacenter. The advance of technology proceeds apace, to be sure, but there is nothing like a recession to motivate companies to take a risk on one – or several – new technologies to cut costs and somehow gain an advantage.

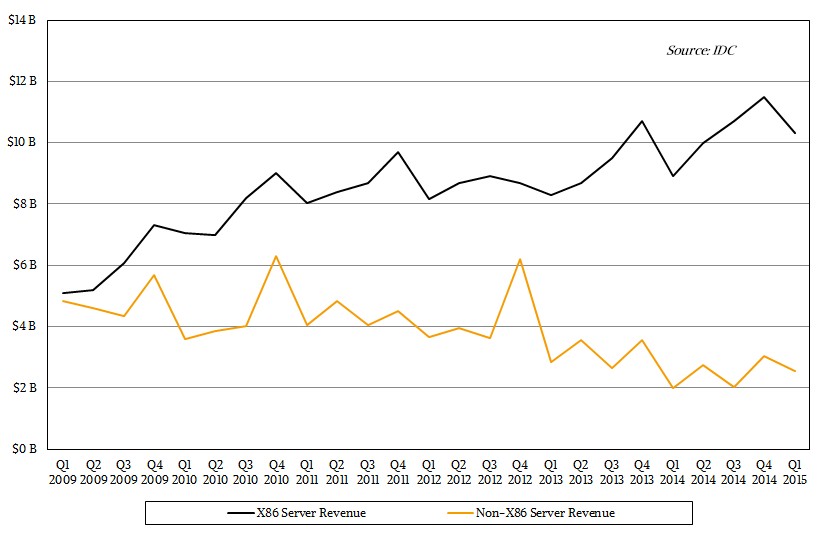

The effects of the Great Recession are still being felt in the datacenter as the X86 platform, by far dominated by Intel’s Xeon products, continues to push other architectures out of the IT budgets.

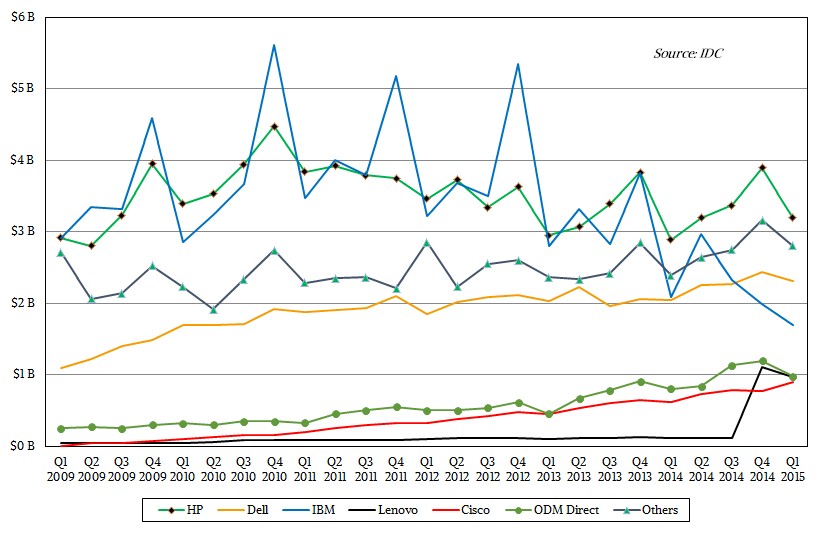

To be sure, other architectures have their ups and downs, and IBM had a good first quarter with the System z13 mainframe refresh, which got underway in late March and which drove $1.33 billion in revenues for the company. That said, IDC estimates that IBM only did a hair under $1.7 billion in sales across its Power Systems and System z lines, meaning that it only did about $358 million in Power-based system sales in the quarter. This is against an overall server market that has shown the best revenue growth we have seen in many years, with shipments up 8.4 percent to 2.3 million units and revenues up 17.2 percent to $12.83 billion. And a server market that has pushed Oracle/Sun and Fujitsu, which were long among the top five vendors, down into the others category and that has seen the rise of Cisco Systems from scratch and Lenovo from acquisition of IBM’s System x X86 server business.

And then there is also the rise of the original design manufacturers, or ODMs, to consider as hyperscalers and cloud builders cut out the middle man and go directly to the companies in Taiwan and China that will make vanity-free systems for razor-thin margins.

The desire to get more flexible and less expensive servers, storage, and switching is not just a ripple effect of the Great Recession, of course, but rather a permanent condition that comes about as companies seek to make their infrastructure more agile and their software more modular and easily updated. The competitive edge was having some sort of sophisticated IT in the 1980s, and in the 1990s it was moving away from proprietary systems and networks to X86 iron and TCP/IP and Ethernet networking, which became de facto standards not because they were the best technology of the time so much as they were the cheaper and then more popular options.

As you can see from the chart above, which is derived from historical data from the box counters at IDC, the market bottomed out in the Great Recession with revenues in the first quarter of 2009 down under $10 billion and quarterly shipments – and this was during massive buildouts at Google, Microsoft, Amazon Web Services, and others, mind you – under 1.5 million units. The gradual trends get obscured by the quarterly-on-quarter comparisons and only looking at things on an annual basis, which is why we bothered looking at the longer trends. To be sure, we should all be happy that the server market has been growing revenues on a quarter-on-quarter basis for since the middle of 2014, but if you just look at that average trend line with your eye, you can see it is trending slightly down even as the shipment numbers are trending upwards and could be soon regularly breaking through 2.5 million units per quarter.

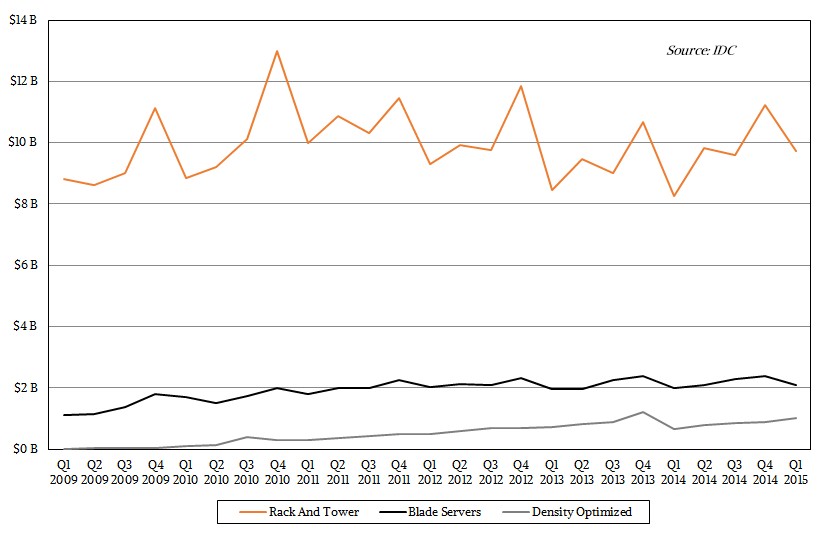

What is going on here? Well, for one thing, density-optimized and minimalist rack servers are becoming more normal as applications are increasingly parallel in nature and servers do not have to be treated like pets that we love but as cows that can be tagged and bred for service without any emotion. The proliferation of servers, considering how many of them are virtualized and running at a reasonably high utilization at this point in enterprise datacenters and how efficiently HPC centers, hyperscalers, and cloud builders try to run their gear, is remarkable. Some of that shipment downdraft in the mid-2000s was not just a nasty recession, but the virtualization downdraft. (We are building a model now of the server and virtualization installed bases to see just what affects virtual machines and containers are having on the underlying server base. Yes, we think this is great fun.)

While big iron systems still make up reasonable portion of server sales every quarter, it is hard to remember sometimes that it was not that long ago when RISC/Unix systems were the hot thing storming the datacenter and X86 iron was more or less relegated to SMBs and deskside serving. Intel has done a stunning job vanquishing all sorts of architectures from the datacenter. Look at the teeth in this chart:

You can see the mainframe and RISC/Unix spikes dwindling down and the X86 platform revenues sawtoothing upwards and to the right. X86 systems are averaging something on the order of $10 billion a year in sales, about double what it was back in 2009 as you can see. And proprietary architectures (as if X86 wasn’t proprietary, but don’t get me started. . . . ) are about half what they were six years ago.

Considering the Moore’s Law improvements in processing capacity over this time, that the lines trend up just goes to show that there is an elastic demand for computing capacity – right up to a certain point. And as it turns out, getting the server racket to generate anything close to $60 billion seems unlikely. The interplay of fixed to down IT budgets, CPU and memory capacity improvements, and efficiency improvements (think about how much more work a server will be able to do without a hypervisor and a minimalist container architecture) make this a very tough business. As tough as the retail business or oil refining or banking.

A lot of noise is made about density-optimized machines, and they certainly are popular with some of the HPC and hyperscaler crowd to be sure, especially with those who are really hurting for space. But as has been the case for the past several years, most of the hyperscalers tend to use rack-optimized systems, although we would be the first to admit that it is hard to draw the lines between a vanity-free rack machine and a density optimized machine sometimes. The point is, the rack server is far from dead and it is certainly not being replaced wholesale by these machines, which we admire greatly.

Tower and rack servers get lumped together in the IDC data, but I expect that the drag in the orange line above has more to do with towers than for racks. Blade servers as we know them have been flatlining since the recovery from the recession, and that is because companies that invested in blade architectures years ago are still filling out their infrastructure. The blade enclosures were architected to last a decade. Revenues for density-optimized machines are certainly on the rise and are certainly impacting sales of blades and racks, but we are a long way from seeing density-optimized machines surpass blades, much less racks. That said, we do expect for traditional enterprise-class blade servers to start waning and other architectures, like Dell’s PowerEdge FX, Supermicro’s Twin, and Hewlett-Packard’s Apollo 2000s to rise over time, and ditto for systems like Microsoft’s Open Compute-compliant Open Cloud Servers.

What matters most to the server industry – and this is important because someone has to build and warrant and support the machines and because no one, not even Google, AWS, Microsoft, or Facebook, actually builds their own iron – is that the server makers create innovative designs and a support structure that meets their needs. The companies need to make a little money to stay in the game, and it takes more and more revenues to do that. This is tough to do, given the staunch competition coming from Cisco and now Lenovo and the handful of ODMs that collectively fight tooth and nail with Dell and HP at the high end for the hyperscale, cloud builder, service provider business.

As you can see from the chart above, the rise of Cisco, which had $890.3 million in revenues (up 44.4 percent by IDC’s reckoning), has been particularly hard on HP, Dell, and IBM. This is one reason why IBM sold off the System x business to Lenovo, although we think IBM sold something off that would help cover its losses on the chip business as much as exiting the X86 server business. (The System x line did not do as badly as IBM made it seem, but it was never going to generate the kinds of volumes and profits IBM needed, either.) Lenovo is now running at close to a $1 billion rate with its X86 server business, and for the first time, the ODM collective also broke through the $1 billion barrier in the first quarter of 2015. Dell, as you can see from its orange line, has steadily risen, too, and has done so with a mix of sales to SMBs, enterprises, and hyperscalers like Microsoft and Tencent.

In the chart above, other vendors include supercomputer makers like Cray and SGI, which sell into an HPC market with its own cycles and challenges, as well as enterprise system makers Oracle and Fujitsu, whose sales are down by about half in the past six years.

IBM’s server revenues have been dominated by the Power and System z processor cycles, which the company has kept out of phase to try to even out its years, and HP has its ups and downs driven by hyperscale and service provider sales and the Xeon processor cycles from Intel. The decline of its Itanium-based Integrity systems business has dampened HP’s revenues, and it is hard to imagine that the high-end Superdome X and NonStop X analogs based on Xeon processors will ever fill in that gap. But anything is possible, particularly if the use of in-memory computing accelerates and companies start running out of memory on workhorse two-socket and four-socket Xeon machinery.

We Are Not Trying To Jinx The Server Market

For those who are slavering over the possibility of the Internet of Things giving a big goose to the server market, we are of the same opinion as Urs Hölzle, senior vice president of the Technical Infrastructure team at Google, who told us on a recent visit that current system architectures would be sufficient to absorb the data processing needs affiliated with machine telemetry.

There are two far more interesting things to contemplate than IoT. One is, what would the market look like if X86 machines just ate the entire market. There’s only $2 billion or so in revenue each quarter left for the X86 architecture to eat. Then what? How does Intel grow beyond that, particularly if more workloads shift to the cloud, more applications get accelerated by FPGAs and or goosed by GPUs, and everything continues on a relentless pursuit of efficiency? And how do ARM server chips come in and upset the apple cart? Can they storm the datacenter, or will they never offer a compelling enough price and performance difference? And let’s contemplate a third thing: Can the OpenPower effort revive the Power platform and make it a threat to the X86 hegemony in the datacenter?

We may need a gut-wrenching recession for us to find out. Not that we are asking for it or trying to jinx anything to satisfy our curiosity. . . .

Be the first to comment