The breakup of Hewlett-Packard into two separate companies – one focused on the datacenter and the other on PCs and printers – doesn’t make any more sense than it did bringing all of these different businesses under the same roof in the first place. But in the next five months, HP will be two separate companies going their own ways, and the company’s hundreds of thousands of datacenter customers are correctly concerned about how the new HP Enterprise, to be run by current CEO Meg Whitman, will be better suited to providing them technology and services.

It is not at all obvious how an HP enterprise business divorced from the PC and printer businesses will somehow be better at riding the technical and economic storms that afflict the datacenters of the world. HP will be as good as it ever was, as best as we can tell. The sales pitch on the breakup is that it will somehow be better as two companies than one. Does this make sense?

Given HP’s reporting of its financial results for its second quarter of fiscal 2015 ended in April and the upcoming Discover customer and partner event next week in Las Vegas, where the breakup of HP will be a hot topic, we thought this would be a good time to drill into HP’s numbers and get a feel for what HP Enterprise – the half of the behemoth that is concentrated on the datacenter – has looked like in the past six years and conjecture about what it might look like in the years ahead.

Breaking Up Is Easier Than Making Up

For the first several years that Meg Whitman was running the IT conglomerate, she was adamant that breaking up the company into several companies did not make any sense, and she dismissed the strategy of her predecessor, Leo Apotheker, who back in the summer of 2011 said that HP was considering spinning off its PC business. As recently as February 2013, Whitman was unequivocal about breaking up HP. “We have no plans to break up the company, and I have said many times we are better and stronger together,” Whitman said in going over the company’s first quarter financials two years ago. “We have a really great set of assets, and we are going to drive better performance. And importantly, customers want this company together. We heard that loud and clear in August 2011.”

Something clearly changed in that time, and the something is that the infrastructure in datacenters is being more precisely tuned for applications, and more and more customers are going with minimalist server designs in a world that, a decade ago, HP and its enterprise server peers were pretty sure would be dominated by high-margin blade systems with converged servers, storage, and networking. HP has done the best it can to absorb these changes, but its financial results over the past five years clearly show the pressure it is under in the enterprise.

HP’s server partnership with Foxconn last year, which bore its first fruits back in March, and its new partnership with Tsinghua University, which we will discuss in a separate story about the dramatic effects that China is having on the datacenter infrastructure market, make the pressures even more obvious than HP’s own financial results. Any business dominated by enterprise customers has a certain kind of inertia, given a large customer base and established buying habits that IT shops develop and are hesitant to change – right up to the point where they aren’t. If HP is pitching hyperscale machines made by Foxconn, switches made by Accton, and now is ceding the infrastructure market in China to the H3C partnership that it is now a minority stakeholder in, something is clearly up.

The issue is that the drive to increase efficiencies in IT has put the squeeze on all vendors for all products and markets. It is like the Great Recession never ended, at least not in the datacenter. And guess what? It never will end. The reason is that automation has finally come to the datacenter and is focused on itself.

To one way of looking at it, Whitman was as absolutely right about keeping HP as one monolithic IT giant just as was Louis Gerstner back in the early 1990s when he came to the same conclusion about not breaking up IBM in one fell swoop. As it turns out, IBM broke itself up, selling off its PC, disk drive, high-end printer, X86 server, and chip manufacturing businesses in the past decade. HP seems to be backing further and further away from high cost, low margin manufacturing and focusing more on being a master distributor of gear that is either made by partners or itself. It will not be at all surprising if HP and IBM eventually decide to stop making datacenter hardware altogether, because the desire for ever-increasing profits push them in that direction. But, what will we need HP and IBM for, then? We happen to think that HP and IBM still have lots of engineering expertise that can be brought to bear in systems, and we are not prepared to write either one of them off just yet.

HP Enterprise, By The Numbers

Here at The Next Platform, we think you have to look at things over a longer view than four quarters to get a feel for what is going on with a technology or a company peddling it. There is no question that HP is under pressure on many fronts and the breakup seems to be as much about giving Wall Street and investors something hopeful to chew on that gives the two halves of the company time to figure out what to do over the longer term. There is still gold in that printer ink, and the profits that the printing business can generate buys HP Inc, as the PC and printing half will be known, some time. But the PC business is tough and Lenovo and Dell are both fighting hard to eat market share there. HP’s worst enemy in printing is storage, which costs less and less each year.

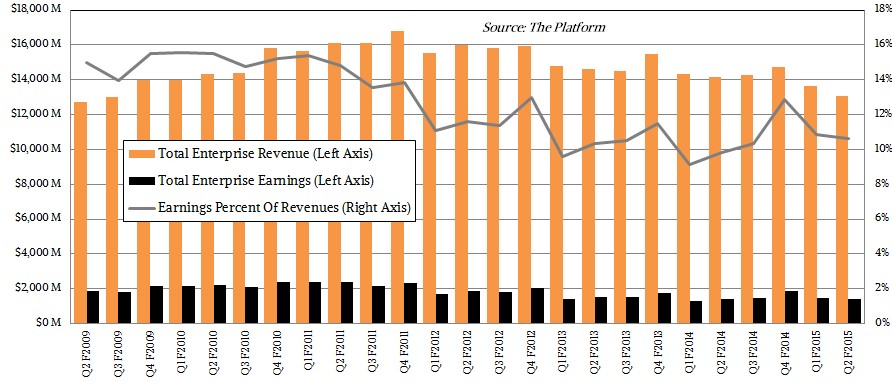

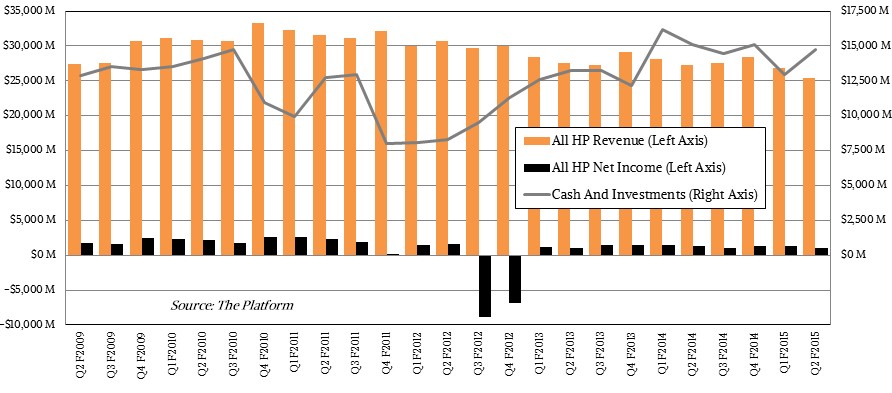

As a whole, HP’s revenues and profits have been under moderate pressure since the end of the Great Recession in early 2009. The company’s revenues and profits peaked at the end of 2010 and the beginning of 2011, as you can see in the chart below:

That was also, not coincidentally, when its profits peaked, thanks to a very big bump in system sales as companies started buying servers, switches, and storage again after deferring purchases in 2008 and 2009. Spending never really stops, of course. Generally speaking, six years ago, HP brought somewhere between 6 percent and 8 percent of its revenue to the bottom line as net income, and it keeps a fair amount of cash on the books. (The cash shown above is not net cash, which would be considerably lower, but the full cash and equivalents is, we think, a better measure than net cash for how much maneuvering room a company has when it wants to pivot. Over the long haul, net cash matters more, of course.)

In more recent quarters, HP’s revenues are slipping and the amount it brings to the bottom line has been slipping such that only somewhere between 4 percent and 5 percent comes in as black ink. The writeoffs on the $10.9 billion Autonomy software acquisition in 2011, on the $13.9 billion EDS acquisition from 2008, and various reorganizations in fiscal 2012 have wiped out a lot of profits. Over the 22 quarters shown in the chart above, net income averages just 2.9 percent of revenues.

You can see why HP wants to do something with these kinds of pressure. But as IBM learned the hard way, selling off the PC business means losing some leverage with chip suppliers, and that means potentially higher prices on server processors. By definition, IBM could never meet the volumes of HP or Dell in the high-volume PC market and that gave Big Blue less leverage with Intel (and to a certain extent AMD when it mattered) on the server front, too. IBM had lower volumes and higher component prices built in, and when the hyperscalers and cloud builders took off, dragging margins on X86 systems even lower, IBM simply could not go there given its cost structure. Ironically, Lenovo now has the PC and server businesses of IBM and it will be able to go there – at exactly the same time that HP will be losing this leverage. This is not the only factor that matters, of course. But volume relationships with Intel are a big factor in determining how profitable a system, storage, and increasingly networking device is going to be.

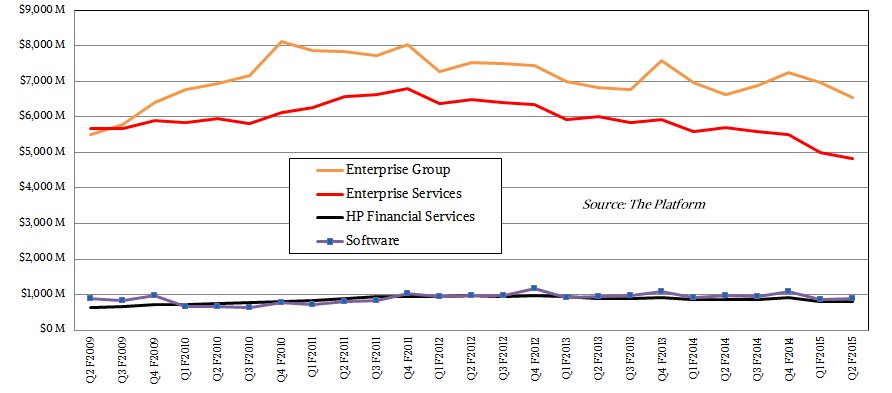

We can get a pretty good idea of what the future HP Enterprise business will look like by combining the financial results of four parts of the current HP: Enterprise Group, Enterprise Services, Software, and Financial Services. Not all of the revenues from these units are focused on the datacenter, but the majority are and it seems to be a pretty good proxy. HP has backcast its current breakdown of revenues and operating earnings for these parts (and others) of its business through fiscal 2011, and we had to do some estimating to reconcile the old reporting to the new reporting for fiscal 2009 and 2010. We think the model is pretty good for those years, but we don’t claim perfection.

What is immediately obvious is that HP Financial Services and HP Software are pretty steady, bringing in somewhere around $1 billion each per quarter, almost regardless of the state of the economy or the competition. Enterprise Group, which includes sales of servers, storage, switches, and tech support services for these systems, came back roaring out of the Great Recession but have been on a slight downhill trend for the past five years. HP has a bunch of issues it is facing in the datacenter, but generally speaking, its Itanium-based Integrity systems business has long since declined and it faces intense competition on the X86 system front. HP bought networking and storage businesses, but more open approaches based largely on sophisticated software and cheaper hardware have made it tough for HP to reap the revenues and profits it no doubt had planned. (This puts HP absolutely in the same boat as the other established monolithic IT players like IBM, Dell, Oracle/Sun, and Fujitsu, so don’t think we are singling HP out in any way.)

Just as Enterprise Group is under pressure, HP’s Enterprise Services behemoth, which is an amalgam of the systems integration and consulting businesses of HP and Compaq and the outsourcing business of EDS, has not been able to grow. And HP said on the call last week with Wall Street that it was going to be cutting out another $2 billion in costs in its services business to get its profits and revenues in synch. Don’t take the wrong idea from these charts. Enterprise Group and Enterprise Services are still very large businesses. The question is how can HP make them more profitable? Partnering for manufacturing and design in segments of the server business (as it has done with Foxconn and Tsinghua University) is one way. But again, with such a partnership, HP loses a skillset and leverage with parts suppliers, and that has its own set of consequences.

If you had to pick one half of HP to own, it would no doubt be HP Enterprise. The temptation to get rid of the outsourcing and hosting businesses that are not particularly profitable must be sorely tempting to Whitman and the team she is assembling to run HP Enterprise. The aggregate of these four businesses had $55.77 billion in revenues in the trailing twelve months and brought in operating earnings of $6.25 billion. (Corporate overhead and taxes are not yet taken out of that number. We will get a sense of these costs when the breakup of HP is done in October.) That yields operating earnings of 11 percent of revenues. That is not terrible for a business that shifts a lot of hardware and has plenty of research, development, sales, and marketing costs.

But as you can see, operating earnings are a lot lower than they were six years ago. The cause of that drop is not just hardware. HP’s Enterprise Services business is the drag. If you look at the trailing twelve months and compare it to the period five years earlier, Enterprise Group has seen a 10.7 percent revenue decline in revenues and a 31.9 percent decline in operating earnings. But over the same period, Enterprise Services has seen a 15.6 percent revenue decline while stomaching a 59.1 percent drop in operating earnings. And this is after several years of restructuring to address issues.

But as you can see, operating earnings are a lot lower than they were six years ago. The cause of that drop is not just hardware. HP’s Enterprise Services business is the drag. If you look at the trailing twelve months and compare it to the period five years earlier, Enterprise Group has seen a 10.7 percent revenue decline in revenues and a 31.9 percent decline in operating earnings. But over the same period, Enterprise Services has seen a 15.6 percent revenue decline while stomaching a 59.1 percent drop in operating earnings. And this is after several years of restructuring to address issues.

To be fair, the strengthening of the US dollar and the weakening of the euro and the yen in the past several years has played havoc with all US-based multinationals who sell a lot of stuff in Europe and Japan.

The issue is that the drive to increase efficiencies in IT has put the squeeze on all vendors for all products and markets. It is like the Great Recession never ended, at least not in the datacenter. And guess what? It never will end. The reason is that automation has finally come to the datacenter and is focused on itself.

Which is why we find it somewhat paradoxical that Whitman and CFO Cathie Lesjak, who will be joining the PC and printer side of HP, are not worried about an additional $400 million to $450 million in annual costs that the separated companies will incur after the breakup. When you factor in supply chain effects, there will be other costs that will eat into profits as well. But HP’s management thinks that the two companies will be more nimble if they are not tied together at the ankles running a three-legged race, and Whitman and Lesjak think they can eliminate around $1 billion in costs to more than cover the extra overhead of running two companies separately. (The other answer might have been to have HP Enterprise run the books and legal and such for HP Inc and charge for it, like a utility.)

It is hard to argue of beastly, monolithic companies that try to do everything, but having spent billions making the HP giant, which we think was not a bad strategy at all excepting the acquisitions of EDS and Autonomy, it seems that the risks of breaking up are the same as the risks of staying together. If the executives were not getting paid largely in stock, you might find them coming to a different set of decisions. And as Whitman said two years ago, customers were clearly against HP spinning off the PC business and they also largely thought that Autonomy was not worth the cash HP paid for it. (History and the courts may yet prove this to be true, too.)

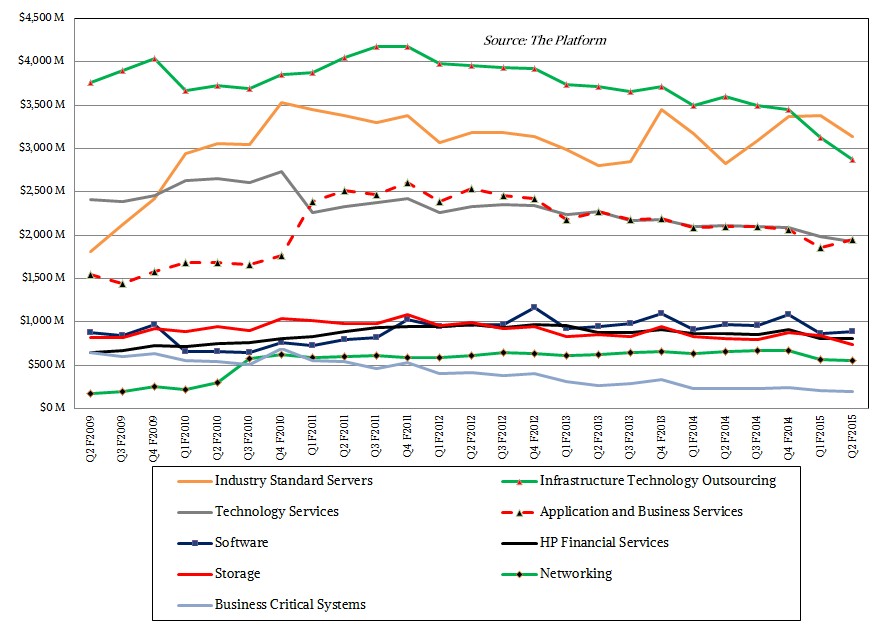

Drilling down into the segments of the HP enterprise business one more level gives us some insight into how the underlying businesses are performing. Take a look:

Yes, this chart is a little busy, but kudos to HP for actually sharing actual numbers about how its various units actually perform each quarter. You very rarely see this kind of granularity among any of the IT players who are publicly traded, and hopefully HP Enterprise will continue to practice. While HP does give revenues for its different enterprise segments, it does not provide operating earnings for any of the segments and we do not have enough data to make guesses.

The flagship Industry Standard Servers unit that is largely the Compaq system business that HP got through its $25 billion acquisition, announced in September 2001 and completed a year later, and it has just surpassed the Infrastructure Technology Outsourcing business (largely from the acquisition of EDS), mainly because that outsourcing business is on the wane just as public and hybrid clouds are on the rise. The X86 server business is humming along at somewhere between $3 billion to $3.5 billion per quarter since server buying picked up to normal levels after the Great Recession ended. Had Cisco Systems not entered the server space, HP might be pulling in $4 billion a quarter in revenues for Industry Standard Servers. But it would probably not have gotten more than that in terms of revenue share. Companies have their habits when it comes to buying systems, and they are hard to charge. This is as true for SMBs as it is for large enterprises and hyperscalers and cloud builders. What can be said of all but the SMBs is that they want multiple sources of gear and they want to be able to place orders and get machines in a timely fashion.

Regarding the most recent quarter, Whitman said on the call with Wall Street that Industry Standard Servers grew 17 percent in constant currency, and that density optimized machines sold particularly well as data analytics platforms (presumably meaning storage-heavy servers). The ProLiant server business rose 11 percent as reported, year on year, to $3.14 billion. Lesjak added that average selling prices were up as HP sold richer configurations and also was seeing a greater attach rate for other products, but that strong sales of density-optimized machines – meaning those minimalist systems sold largely to hyperscalers and cloud builders – put pressure on margins. Even though Business Critical Systems, which includes Itanium-based Integrity machines as well as the new Superdome X and NonStop X iron based on Xeon chips, had a 15 percent revenue decline (10 percent at constant currency), gross margins for the line improved.

Storage revenues, which hover at around $800 million a quarter, were down 8 percent as reported to $740 million in fiscal Q2 2015; the decline was only 2 percent at constant currency. Traditional storage arrays had weaker sales than expected, as did the EMEA region when it came to storage. Lesjak said that the 3PAR line plus so-called converged storage, a grab bag meaning new-fangled stuff, had “solid growth” and gained market share. HP has not yet integrated Aruba Networks into its networking business, but that will help stem some of the declines. The networking business, which roughly doubled in the wake of the $2.7 billion acquisition of 3Com in November 2009, had a 15 percent decline in the latest quarter, and China was a big problem there – hence the sale of the H3C business to Tsinghua University, converting an HP division into a state-owned business in China that has HP owning 49 percent of it.

Given all of these numbers and all of the changes going on in the datacenter, we do not think that breaking off the enterprise part of the current HP business will change much other than the company’s market capitalization and its ranking in the Fortune 500. And as far as we are concerned, none of these matter very much.

What does matter is how HP competes as a supplier of hardware and services. If HP had been an innovator in the public cloud, starting around the same time as Amazon Web Services a decade ago, it might have a much larger services business that consumed a lot of its own iron, but then it would probably not have Microsoft as a customer for systems for the Azure cloud. An operating system for X86 machinery would have been useful, too, and so would have been a homegrown hyperconverged server-storage hybrid that took off like Nutanix. On the client side, like rival Dell, it probably would have been best for HP to not have missed the smartphone and tablet revolutions.

It is hard to do all things and ride all trends to profits. In fact, it is impossible, which is why no company – not even diverse ones built up over time like HP – have ever done it.

Be the first to comment