Facebook’s social network is free, but that does not mean that the company’s 1.2 billion users do not have expectations for uptime and durability of the photos and videos they store on the service. Quite the contrary. And making sure that all of our photos or videos are always available turns out to be a massive – and massively expensive – engineering job.

Back in the late 2000s, when Facebook was smaller but still at hyperscale, the company created its own distributed object storage system, called Haystack, and while this repository is still the primary data store for all of the online application’s assets – including photos, videos, code snippets, text, and so on – it has evolved over time to be more efficient. Jason Taylor, vice president of infrastructure foundation at Facebook, tells The Next Platform that in the early days that Haystack kept multiple copies of photos on the system for redundancy and durability. (Those pictures of your cats and children can’t be lost, after all, or you will get mad at Facebook.)

But a few years back the company saw the growth curve for users and their media hoarding habits and decided it had to come up with a better way to archive data so it could lighten the load a bit on Haystack.

Back when Haystack was revealed six years ago, it had been in production for a while and had a mere 15 billion photos, which had four copies spread across the object storage, and the quadruplicated archive weighed in at a mere 1.5 PB; users were adding about 30 million photos per day. When the cold storage effort was first unveiled as a project back in January 2013 at the Open Compute Summit, Jay Parikh, vice president of infrastructure (meaning he is in charge of the whole hardware and software enchilada at the software network) said that Facebook’s over 1 billion users had uploaded more than 240 billion photos and that they were adding over 350 million photos a day. At the time, those incremental photos were consuming 7 PB of storage a day and the photo archive alone was well into the exabytes. (Facebook has not said how large the archive is.) Today, Facebook users are uploading 2 billion photos per day, and if the ratio of photos to storage capacity is the same now as it was two years ago, that works out to 40 PB of disk capacity per day that has to be added to store them.

It is no wonder that Facebook, trying to reach 5 billion users and looking at that kind of growth, decided to create a disk-based cold storage system.

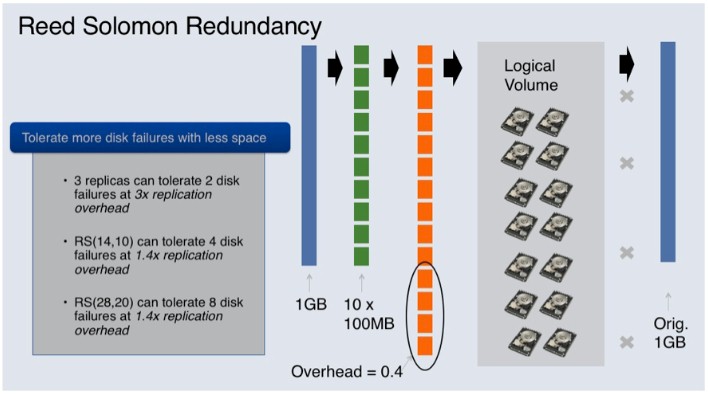

With Haystack, as Taylor explains it to The Next Platform, Facebook dropped back to three independent copies of a photo on storage servers protected by RAID 6 controllers, which stripe the data across multiple drives and use what are called Reed Solomon encoding to create parity data that allows for the data on a disk to be recreated from the others in the event that it fails. (Reed Solomon encoding is used on all sorts of storage devices and network and signal transmission gear.)

“We have gone through a number of iterations of that Haystack storage system, and the main change has been to take that Reed Solomon encoding and use it in two different contexts,” explains Taylor. The first is to use the encoding to ensure the availability of a photo stored in the Haystack hot storage, but not using RAID disk controllers, but software running in the servers. Taylor says that Facebook will probably keep all photos hot in the Haystack storage going forward because Facebook users want their photos now and the latency of pulling it from cold storage – even for old and frequently unused photos that make up the vast majority of the archive – is too high. “The gain in efficiency here with cold storage is that instead of keeping three copies of the data hot, we can keep two copies or even one copy. If you have a backup, you can take a little more risk and you can essentially take a portion of those Haystack resources and make them cold.”

Reed Solomon encoding is also used to stripe data across storage servers in the cold storage.

Cold As Ice

The cold storage effort was headed up by Kestutis Patiejunas, a software engineer at the company, and he says that the idea was to create a backup for Haystack that would ensure the durability of those hundreds of billions of photos and videos and would not have the very long latencies of tape libraries commonly used in the media and entertainment business to archive data inexpensively. Facebook wanted something that performed like a disk and cost more like tape. And so the engineers got to work.

As a baseline archive machine, Patiejunas and his team started with the Open Vault storage server that Facebook developed along with its Open Compute servers and the Prineville, Oregon datacenter that was its first homegrown facility. (Up until then, Facebook bought custom servers, largely from Dell’s Data Center Solutions unit, and leased space in co-location facilities.) The cold storage has now been in production for more than a year in Prineville and as well as in the Forest City, North Carolina datacenters, and Patiejunas says that Facebook has some interesting ideas about how to improve its archiving once cold storage is fired up at its datacenters in Lulea, Sweden and Altoona, Iowa.

Because the cold storage facility is an archive rather than hot storage, Facebook programmed the Open Vault storage servers to be dormant most of the time. In fact, disk drives are only fired up as they are needed to retrieve data to send back to Haystack if it is going to blow a disk drive or a whole server. To be even more stingy with the electricity, only one drive per Open Vault tray could be powered up at a time. Data encoding a photo is spread across multiple Open Vault storage servers, much as a RAID disk controller stripes data across multiple disk drives in a single system. Because most of the disk drives are dormant in a rack, Facebook’s engineers could chop out a whole bunch of components from its regular Open Vault storage, which powers Haystack, and thereby radically cut back on the power in use by the cold storage datacenter, which is off to the side of the compute and storage datacenters.

As Patiejunas explained in a blog post, the engineers cut out two of the six cooling fans in the Open Vault, cut the power shelves from three to one, and cut the power supplies in the shelf from seven to five. A full Open Rack of Open Vault storage using 4 TB 3.5-inch drives could house 2 PB of storage and they only burned 2 kilowatts of juice. That gives Facebook the ability to archive 1 EB of storage with only 1.5 megawatts. The cold storage facilities have a lot of redundancy in power distribution removed from them – again, they are an archive, not a production system, so uptime does not have to be 100 percent – and uninterruptible power supplies are also not in the cold storage datacenters. The upshot is that the cold storage versions of the Open Vault arrays cost one third of what the regular Open Vaults used to power Haystack cost, and the datacenters, which are extremely bare bones, cost one-fifth as much as the compute and storage halls that run the Facebook applications.

Chilling With Blu-ray

While Facebook was all fired up about disk drives that had shingled magnetic recording, or SMR, methods to put data on disks when it first started loading up the Prineville cold storage datacenter and when Forest City was just coming online back in the fall of 2013, it has been a little bit less aggressive in adopting SMR drives from Seagate and HGST Patiejunas tells The Next Platform that while Facebook has been examining denser disk drives, which come in 6 TB and 8 TB capacities these days, it is still nonetheless using 4 TB drives in the cold storage facilities “because they are at a good price point.” (Presumably when you buy lots of them, as Facebook does, the pricing is a bit different.) That said, Taylor explains that Facebook is still interested in SMR technology, even if they are more sensitive to vibration than normal disks, because the prospect of a 10 TB, 20 TB or 30 TB disk drive can help keep the storage server farms in both hot and cold storage from growing as fast as they might otherwise.

Another lesson that Facebook learned is that it should make its Reed Solomon encoding levels flexible rather than static across its cold storage.

“People talk about their encoding and they just throw around these numbers, but encoding has to be related to something in the real world,” warns Patiejunas. “And specifically they have to be related to disk drive failure rates. Selecting fixed numbers for encoding is probably not the smartest way because as hardware changes or conditions change, that 10/14 encoding might be too aggressive or not aggressive enough. We had the change the cold storage in the middle of building it to have an architecture where the encoding is flexible. This gives us the ability to add more protection dynamically if a new technology is less reliable. We can use the dial and if the disks are less reliable, I can add more compute and more network. If it is more reliable, I can use less compute and network.”

The other course correction that Facebook took in the middle of the rollout of the cold storage facilities is to do away with a file system on the cold storage. As it turns out, the file system that Facebook was using has about 1 million lines of code, and it gets driven a little nuts as drives are powered up and down as the cold storage does its magic. So Facebook cooked up a Raw Disk File System, which has about 10,000 lines of code, that allows for the disk drives to be addressed more directly as data is put on them or read off them, and one that doesn’t go haywire with the power cycling. This raw file system has been in production for over a year bow, and Patiejunas says that it will eventually be made open source.

Looking ahead, Facebook is thinking about what it can do to protect data once it has four cold storage facilities. Right now, the Prineville cold storage facility is backing up data from the Forest City data center’s Haystack storage, and vice versa. This provides some geographic separation between primary data and backups. When the other two datacenters in Sweden and Iowa have their own cold storage add-ons, Facebook is going to have what amounts to four very large disk drives attached to its network, and then it will be able to apply Reed Solomon encoding across those four datacenters and stripe all of the Haystack objects across all four cold storage facilities. Much as the data was striped by RAID 6 arrays or across nodes in the cold storage racks. This way, Facebook can lose one of its four cold storage facilities and still run the encoding in reverse to recreate any data that has been lost inside of the Haystack object storage.

Facebook is also moving a prototype cold storage array based on Blu-ray discs from a science project into production to augment the disk-based cold storage facilities, according to Taylor. Facebook divulged the Blu-ray archiving system at the Open Compute Summit in January 2014, and it is based on a 48U (that’s seven feet tall) rack that is capable of holding 1 PB of data in a single rack using 100 GB Blu-ray discs. You might be thinking that this is not so great, considering that Facebook can get 2 PB in a rack of cold storage using 4 TB drives, but the roadmap for Blu-ray is to push from 100 GB to 200 GB to 500 GB and eventually 1 TB discs, and importantly, the cost of a unit of capacity on a Blu-ray disk is a lot lower than it is on a disk drive.

“We are working to roll that into production, probably later this year in pretty large volume,” says Taylor. “And through 2016, we will have a large number of Blu-ray racks, and by large number I mean hundreds of petabytes rolling into production. It is a great technology with a pretty reasonable roadmap.”

Parihk said when the Blu-ray machine was divulged that it would use 80 percent less electricity than the cold storage version of the Open Vault, so that puts it around 400 watts, and would cost about 50 percent less, presumably on a cost per GB basis. It is unclear if this pricing that Facebook was predicting is panning out, and Taylor was not going to reveal any secrets, but said that Facebook “never pursues a technology unless there is a step function reduction in cost.”

The Blu-ray library fits in an Open Rack form factor and has 16 disc burners and two banks of a dozen magazines holding the discs, one bank on each side of the rack. Each magazine holds 36 cartridges and each cartridge holds a dozen discs, and if you do the math that is 10,368 discs per cabinet and just a little over 1 PB of capacity. Over time, that Blu-ray library will push up to 10 PB per rack, if the Blu-ray roadmap holds.

Be the first to comment