Branching out from the HPC sector into the enterprise does not necessarily require supporting operating systems other than Linux. But in many cases, the ability to run Windows applications is a necessity in the enterprise, and for workloads other than the core Exchange Server and SQL Server workloads that dominate the Windows part of the datacenter, too. With its latest UV 300 machines, which are clearly aimed at enterprise customers, SGI is only supporting Linux. But a recent demo shows the path that SGI will likely take to bring Windows, and possibly other operating systems, to the UV shared memory systems.

The ability to run Windows on the UV systems is something that SGI executives have noted in the past that is important to expand the addressable market of these shared memory systems, and the original “UltraViolet” Altix UV 1000 systems, which debuted at the SC09 supercomputing conference in the fall of 2009 and started shipping to customers in May 2010, had support for Windows Server 2008 R2 added to them in February 2011 as SGI tried to push its big iron into more commercial accounts.

The initial Windows Server 2008 support was for the Datacenter Edition of the operating system, which at the time could scale to 128 cores (or 128 threads and 64 cores if customers had HyperThreading simultaneous multithreading turned on) and 1 TB of memory in a hardware partition on an Altix UV 100 midrange or Altix UV 1000 high-end NUMA box. But a few months later, Microsoft and SGI had worked to push that up to 256 cores or threads and 2 TB of memory, which was the maximum limit of scalability of Windows Server 2008 R2. This did not even come close to denting the 2,048 cores and 16 TB of memory that the UV 1000s have.

Expanding The Market For UV

At the time, SGI was talking about expanding into the commercial area with a two-pronged Linux-Windows approach, and when SGI did the total addressable market math four years ago, it reckoned that traditional HPC simulation and modeling represented a $1 billion market. Replacement of RISC/Itanium Unix systems with either big Linux or Windows boxes represented another $1 billion potential market for the UV machines. Various kinds of data analytics workloads, including running Oracle and SQL Server databases, both of which were certified to run on SGI big iron, as well as Hadoop batch processing and Memcached in-memory processing were assessed at another incremental $1 billion opportunity for the UV iron. In essence, the push into the commercial space and the adoption of Windows tripled the company’s addressable market. But for a lot of reasons, SGI didn’t triple its actual market in the past four years.

Part of the problem is that it is very tough and expensive to certify a wide variety of commercial applications on both Linux and Windows. But it looks like SGI has an answer to that, and it looks like it is the combination of the OpenStack cloud controller and the KVM hypervisor running atop its UV machinery. The other problem – and one that SGI has fixed by bringing out the UV 300 machines, which The Next Platform described in detail a few weeks ago –is that its high-end UV 2000 systems require a lot of tuning for workloads because of the NUMA architecture of the machines. With the new NUMALink 7 interconnect used in the UV 300s, the interconnect provide uniform, rather than non-uniform, memory access across its nodes. And that means it looks almost like an old-school symmetric multiprocessing (SMP) system as far as operating systems and applications are concerned. This means a lot less tuning. The UV 300s also start out as a much smaller system, scaling from four sockets of Xeon E7 v2 processors all the way up to 32 sockets and a maximum of 24 TB using 32 GB memory sticks. (You can push that to 48 TB with 64 GB sticks.)

Today, the high-end UV 2000 systems bring 256 sockets, 2,048 cores, and 4,096 threads of compute and 64 TB of shared memory to bear on massive scale-up workloads, but the entry point is a full rack. The systems launched back in the summer of 2012 with a tuned up version of SUSE Linux Enterprise Server 11. (SUSE Linux is the foundation of the Linuxes used by both SGI and Cray for their respective UV and XC series of massively parallel machines.) While Windows can be supported on these machines, SGI has not stressed it even though it has taken down some big Windows deals. But with the new UV 300 shared memory systems, which represent a better chance for SGI to push into commercial accounts, Windows is not formally supported as a standalone, bare metal operating system. There are more ways to skin this Windows cat, however.

The answer, of course, is to virtualize the machine and run Windows inside of virtual machines, and that is precisely what SGI has shown off in a recent demo. SGI has not formalized such support as yet, but it stands to reason that this is the path that the company will take going forward to bring Windows and other operating systems aside from its variant of SUSE Linux to The Next Platform.

In the demo, SGI has loaded up an unspecified UV machine with SUSE Cloud, the commercial Linux distributor’s bundling of the OpenStack cloud controller atop the SUSE Linux kernel. While the SUSE Cloud variant of OpenStack can support the Xen (from Citrix), KVM (from Red Hat), or Hyper-V (from Microsoft) hypervisors, but it stands to reason that KVM will be the hypervisor of choice, given its momentum on OpenStack. KVM is certified to run on the UV 300 machines, as is SUSE Linux Enterprise Server 11 and Red Hat Enterprise 6. (SLES 12 and RHEL 7 are not yet certified.)

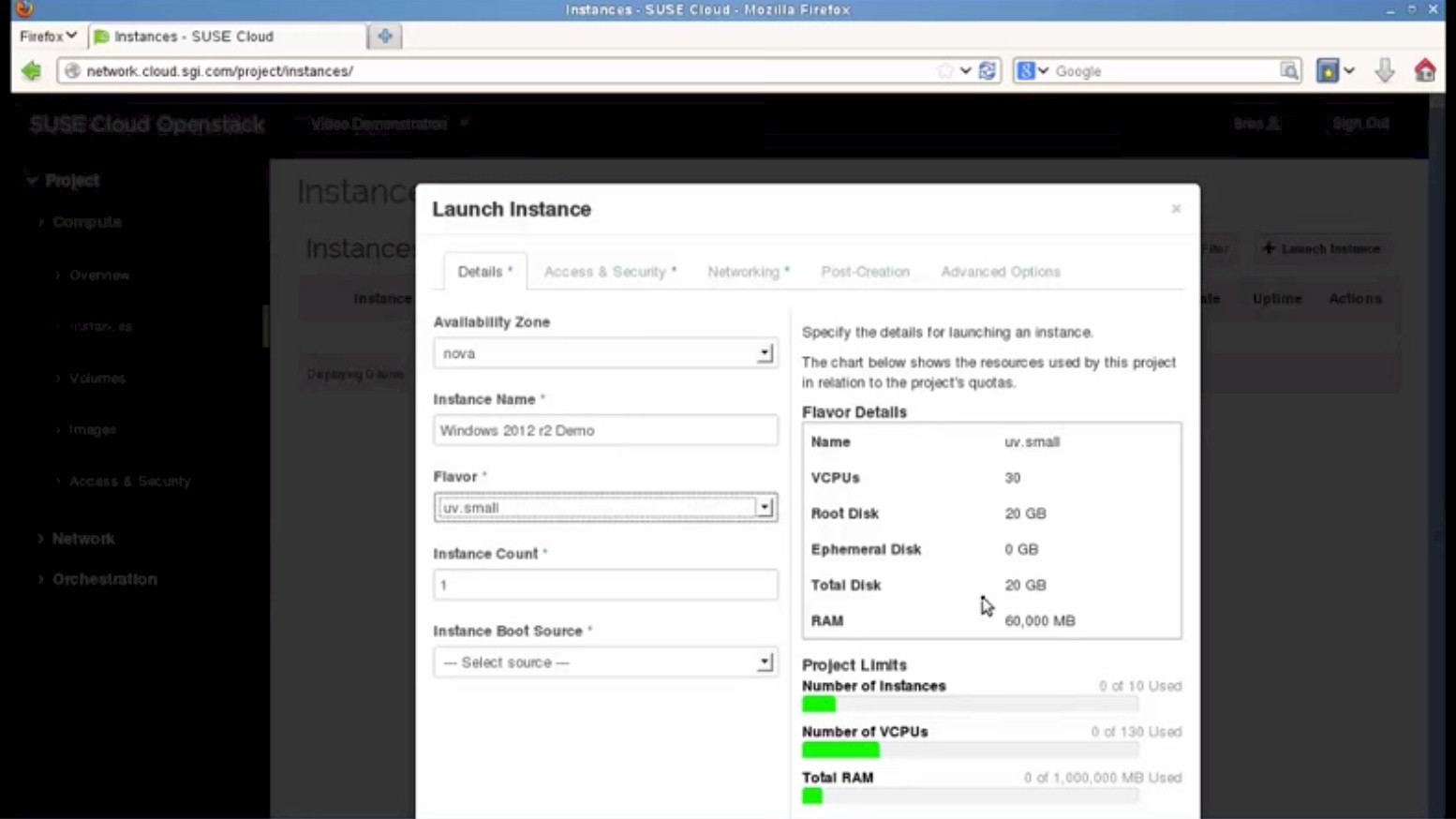

In the demo, SGI showed off how SUSE Cloud could be used to create a partition with Windows Server 2012 R2, the latest and greatest Windows operating system, atop of an unspecified UV machine:

As you can see, this demo slice was a small partition configured with 30 virtual CPUs, 20 GB of local disk storage, and 60 GB of memory. SGI said in the demo that running atop SUSE Cloud, Windows Server 2012 R2 could extend up to 120 cores and up to 128 GB of memory, and this could be the limit of the virtual machines on the hypervisor (presumably KVM) when tuned up for the UV machines. Those seem like odd limits, given the scalability of Windows Server. The original Windows Server 2012 scales up to 64 sockets and 640 logical processors with Hyper-V turned off and up to 64 sockets and 320 logical processors with Hyper-V turned on.

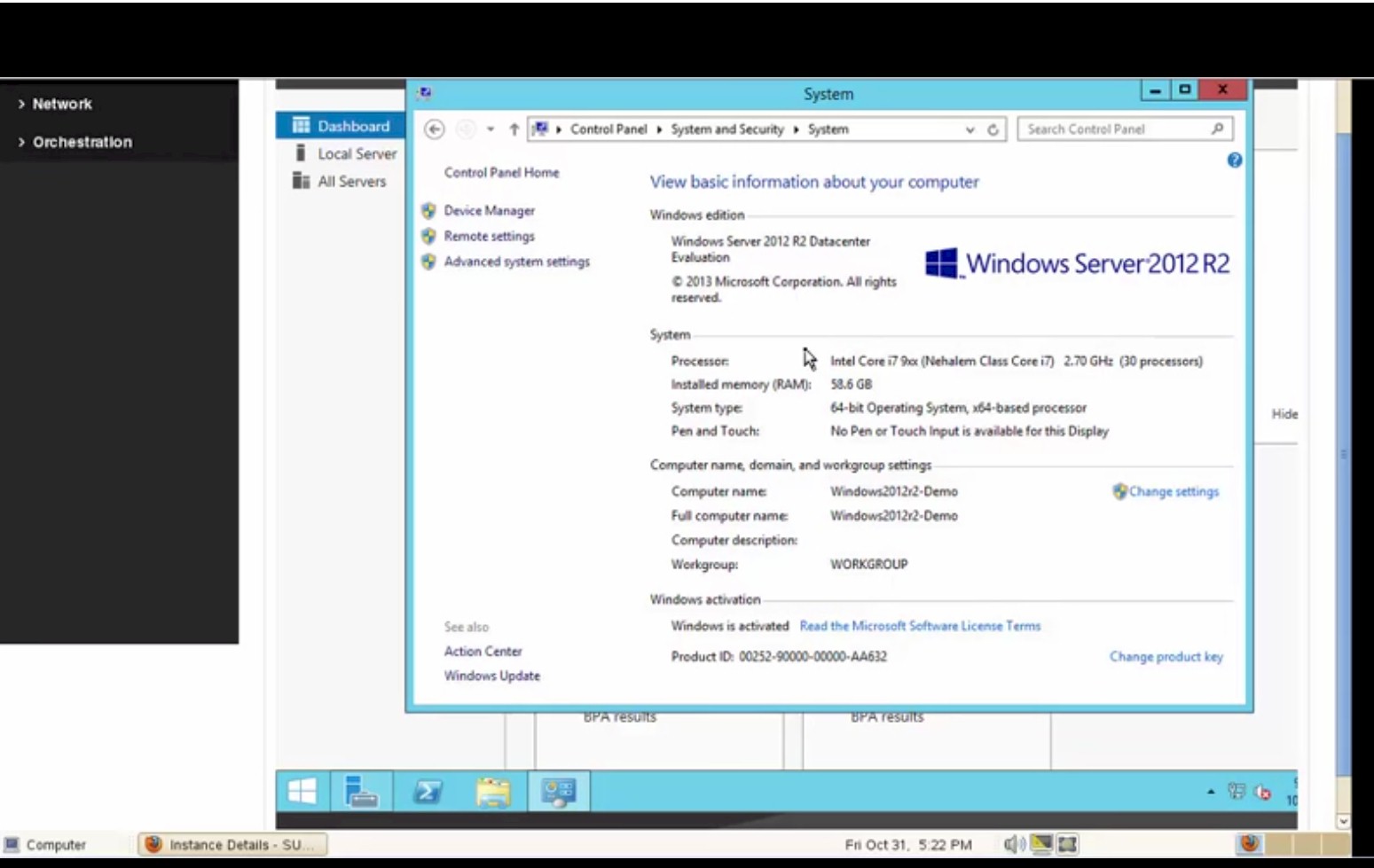

Here is the SGI techie doing the demo showing that Windows Server 2012 R2 has been deployed by the “Nova” compute controller part of OpenStack and is actually running on the UV iron:

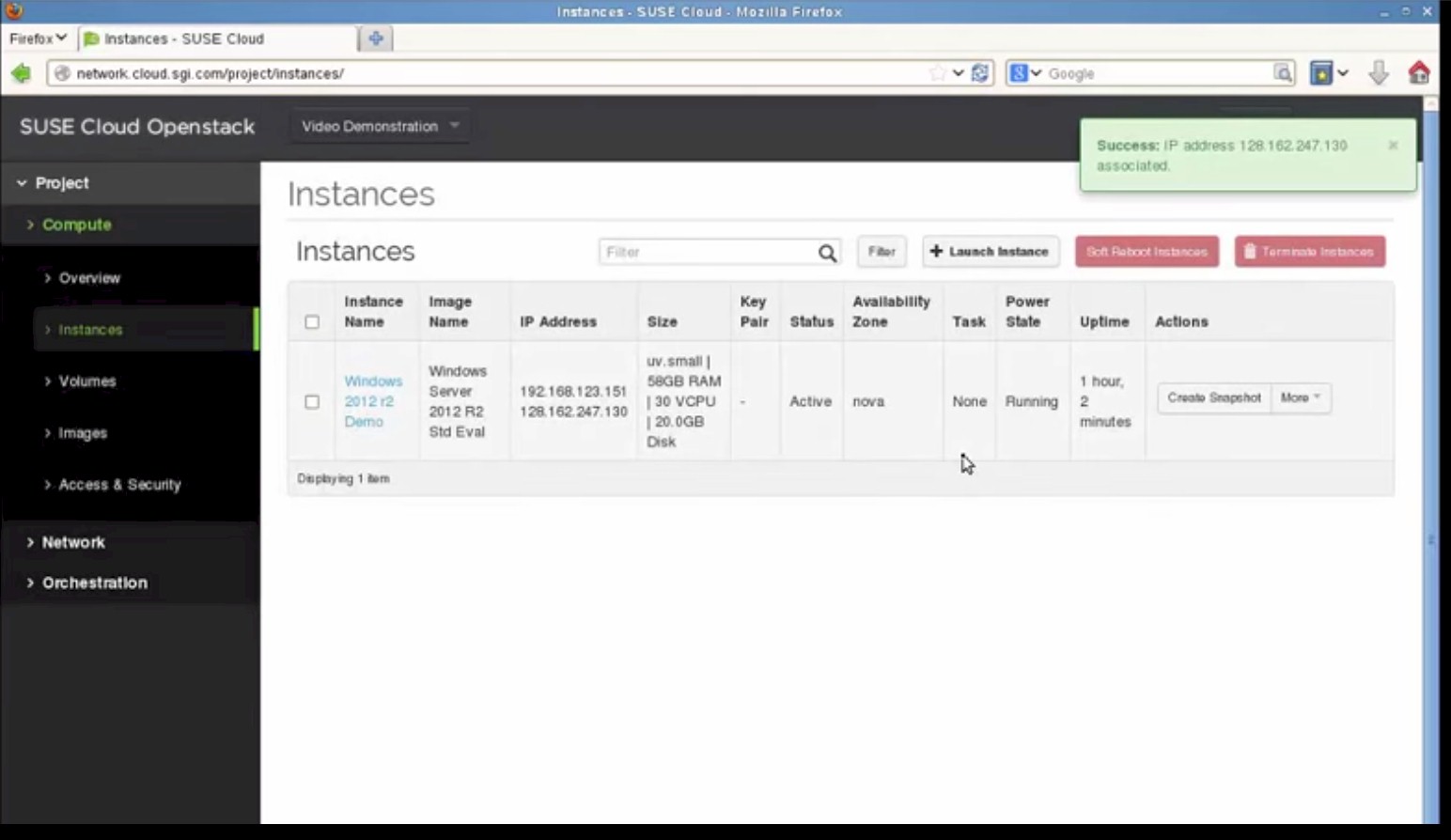

The fun bit is that Windows Server identifies the processor on the machine as being a Core i7 9XX desktop-class processor, which it most certainly is not. And here is the instance being configured with the “Neutron” virtual networking controller to the network:

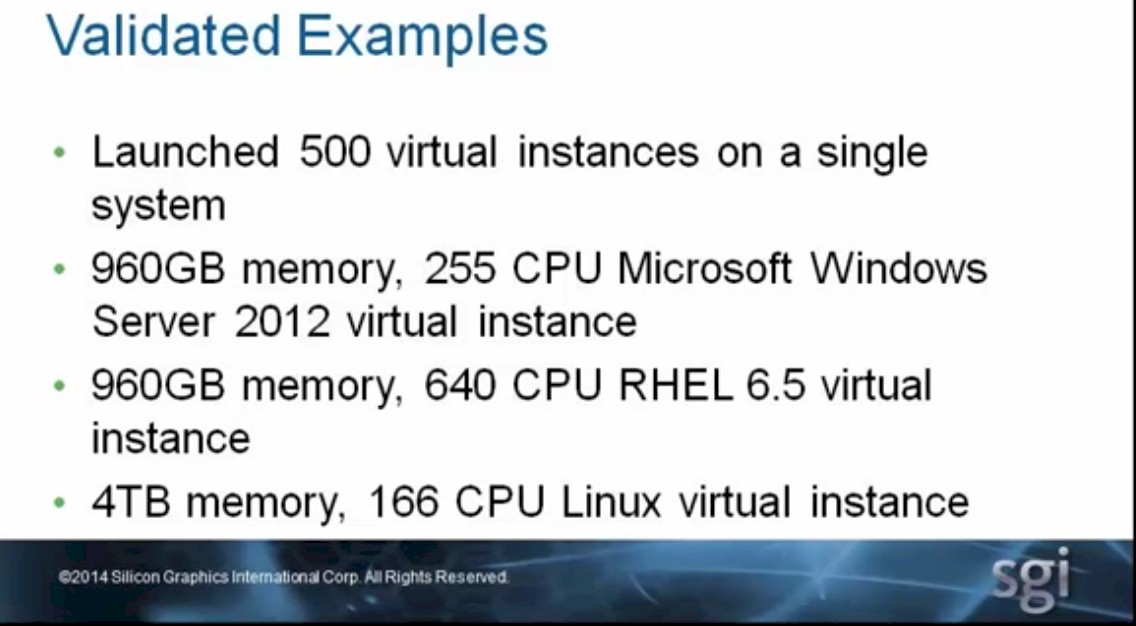

SGI has been playing around with supporting both Windows Server and Red Hat Enterprise Linux atop SUSE Cloud, and here are some of the tests it has done up to the point when this demo was put together, which looks like it was during the SC14 supercomputing conference last year:

For the commercial customers that SGI is going after, the UV 300 machines are probably best suited to run SUSE Cloud and a KVM hypervisor to support Windows or RHEL or any other operating system that can be deployed atop KVM. The UV 300s use Xeon E7-8800 processors with six, ten, twelve, or fifteen cores, so a 32 socket machine would top out at 480 cores and 960 threads and 24 TB of memory today. You could put a lot of Windows Server 2012 R2 instances on such a machine.

This would be particularly useful for multiple Windows workloads that share data. Virtual machines could communicate with each other over the NUMALink interconnect inside the system instead of being run on distinct physical servers with much slower Ethernet links. Moreover, for some applications in life science or analytics, where Windows applications are favored even if they don’t dominate, putting Windows on a UV 300 would allow those applications to scale up to much higher core counts and memory sizes than is possible on the Xeon workstations or servers a lot of shops employ today. In essence, a UV 300 could become a giant shared workstation. It will be interesting to see if SGI can work with Microsoft to push the scalability limits of a virtualized Windows instance running atop KVM even further, and if the Windows ISVs most suited to sell their wares on such a machine will also push upwards the scalability of their applications. Scalability does not just happen magically because the hardware makes more threads and memory available to the operating system, after all.

Hi Timothy – this opens up a lot of options for KVM and OpenStack. The future for OpenStack admins is definitely getting brighter.

The article does not mention this, but since Data Center edition is only offered via OEMs with vendor support, it would appear that SGI secured Microsoft help in supporting Windows on top of OpenStack and kvm hypervisor. I probably missed the news when this was announced, but it’s exciting nevertheless.

I think it was a demo, but I suspect that this will be the formal way that Windows and perhaps other environments will be supported on SGI iron going forward. SUSE Linux for native stuff and KVM for virtual stuff.