If you think that the giants of the hyperscale and cloud world have a hankering for minimalist, custom servers forged by original design manufacturers, you should see the appetites they have for their storage gear–it is a lot larger perhaps than many realize.

The rise of hyperscale web applications and commercial clouds is having a dramatic effect on the market for both servers and storage. The hyperscalers and cloud builders operate at a much larger scale than most enterprises, and are keen to remove as much cost as possible from their systems since, after all, these machines in their datacenters are literally where they sink costs and where they make money. Cutting costs often means circumventing the traditional server and storage suppliers and going directly to original design manufacturers. These ODMs now account for a significant portion of these two markets, and perhaps more significantly, are responsible for most of the growth for these devices.

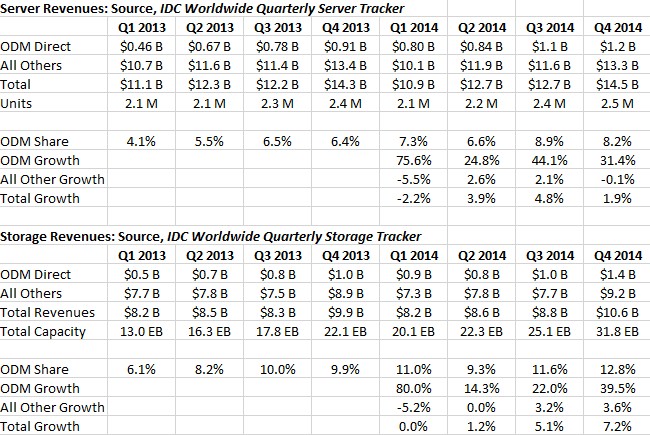

That assessment is based on the latest data from the analysts at IDC, who have just put together their server and storage trackers for the fourth quarter of 2014. IDC has been tracking the server count and revenues from the ODM manufacturers for a while, and has started to do the same in the storage area more recently.

While people talk about hyperscale and cloud companies building their own servers, it is actually rare for any company to make their own servers or storage arrays. What companies like Google, Amazon, Microsoft, Facebook, and others do is work with the ODMs to spec out machines for their particular workloads and then have the ODMs actually build the boxes. In some cases, the hyperscalers and cloud builders work directly with makers of CPUs, disk drives, flash storage, and other components to buy parts in bulk and then have them shipped to their ODMs, and in other cases the ODMs leverage their own supply chains to buy parts for the machinery.

The big ODMs are not as well known as the traditional IT suppliers, but they are becoming more famous as hyperscalers and cloud builders talk about deals and as the ODMs expand their businesses, particularly in the United States. The big ODMs include Quanta Computer, Foxconn, Wistron, Synnex, Jabil Circuit, and a few others. And then there is Supermicro, which sometimes looks like an ODM and sometimes looks like a tier one player.

Complicating the analysis of the market a bit is the fact that some of the tier one server makers, including Hewlett-Packard, Dell, Lenovo, and others, have custom server and storage lines that they sell against the ODMs at these large hyperscale and cloud shops. These machines are not included in the IDC data for ODMs. So it is important to not think that the ODM category in the data represents all of the bespoke machinery that is being acquired for datacenters the world over. The ODM revenue figures presented by IDC probably account for a little more than half of the revenue for all custom server and storage gear that gets made in a year, but sales in any given quarter can vary wildly because Google, Microsoft, and Amazon place very large orders, sometimes at the same time, sometimes not.

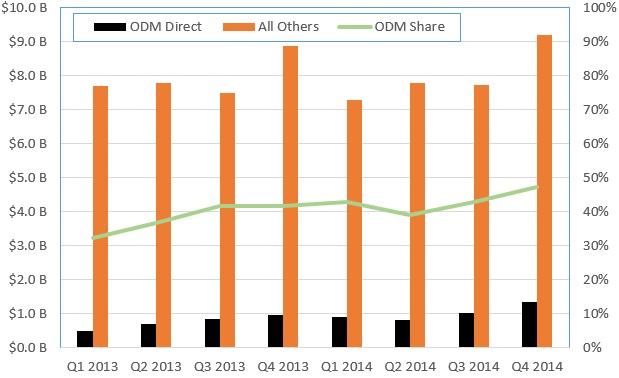

On the server front, total revenues across all types and geographies rose by 1.9 percent to $14.54 billion, with shipments up 2.8 percent to 2.5 million units. Revenues by ODMs selling directly into customers sites accounted for $1.19 billion in sales, an increase of 31.4 percent compared to levels set in the fourth quarter of 2013. Looking at the historical data for the past eight quarters from IDC, the ODM slice of the server pie has grown steadily since the first quarter of 2013 and has doubled its share of the pie, in fact. In Q1 2013, the world consumed $11.1 billion in servers and only $455 million of that came from ODMs; that works out to the ODMs having 4.1 percent of worldwide server revenues. (Shipment figures for the ODMs were not available as The Next Platform was going to press.) Fast forward four quarters, and ODMs have an 8.2 percent share of the sales for servers worldwide. That ODM share wiggles up and down a bit, but the trend is clear in this table that shows ODM server and storage sales compared to the non-ODM portion:

Drilling down into the server data a bit more for the past four quarters, as we have done in making the table above, reveals that most of the growth in the server business recently has been because of the ODMs. If you extract the ODM sales figures from the overall server figures, the remainder of vendor sales done either directly or through channel partners was down in the first and four quarters of last year, and growth for the non-ODMs was weaker than the market overall. If it was possible to back out the bespoke server sales by those tier one server makers who have such businesses, we suspect that the remaining sales, comprised mostly of sales to enterprises that use standard rather than custom machines, would be down even lower. How much lower is hard to say for sure.

Looking at such figures makes it obvious why Hewlett-Packard has been working with Foxconn to put together a set of hyperscale machinery that will better appeal to the cost-conscious customers who want minimalist designs and sometimes machines that are inspired by or adhere to Open Compute Project specifications. HP is not the only one looking for a way to make a buck on machines that are aimed at hyperscale and cloud workloads and that are less costly and often more dense than its standard enterprise-class servers. Cisco Systems, which was the upstart in the server business with its converged server-switch machinery sold under the Unified Computing System name, launched its own hyperscale line last fall. Cisco has done a remarkable job catapulting itself into the tier one upper echelons of the server business with the UCS iron, but its growth has slowed and it has to seek out growth in new and adjacent markets. Similarly, Lenovo bought IBM’s System x X86 server division in part to use the profits from the enterprise side of the X86 server business to help fund Lenovo’s own expansion into custom servers that it is selling against the ODMs. Manufacturing scale and supply chain matters like never before in the server business.

The same trend away from the big, established suppliers and towards ODMs is happening in storage, too. In its latest quarterly storage tracker report, IDC says that companies consumed a stunning 31.8 exabytes of disk storage capacity in the final three months of last year, representing a 43.7 percent jump from the same period in 2013. IDC reckons that ODMs drove $1.36 billion in storage revenues, selling directly to hyperscale, cloud, and large enterprise customers that are looking for minimalist storage for their modern applications. ODM storage revenues grew by 39.5 percent in the fourth quarter, outpacing even the appetite for ODM servers. At 12.8 percent of revenues, the ODM slice of the storage pie is even larger than it is in the server market. And once again, the ODMs are accounting for a lot of the growth in the storage array business – about half in recent quarters, if you do the math.

But these are not the astounding statistics buried in the data that IDC has compiled. The ODM figures for storage show just how focused on data, rather than compute, the modern hyperscale and cloud facility is compared to the enterprise datacenters of days gone by. One unique bit of data in the stats is that the size of the ODM server and ODM storage businesses that are roughly the same and, in fact, now the ODM storage business is, by IDC’s reckoning, larger than the ODM server business. In the fourth quarter, ODM servers accounted for $1.2 billion in revenues, compared to $1.4 billion for ODM storage. Since the dawn of the computer age, server revenues have always been larger than storage revenues in the industry.

But even more astounding than that is the amount of capacity that ODM storage customers are buying. Two years ago, ODM storage customers consumed about 4.2 exabytes of raw capacity out of about 13 exabytes consumed by the entire industry in the first quarter of 2013, Eric Sheppard, research director for storage at IDC, tells The Next Platform. In the fourth quarter of last year, when an astounding 31.8 exabytes of storage capacity was sold worldwide, 15 exabytes of that was consumed by the hyperscaler and cloud builders who go to ODM partners for gear. And here’s the fun bit: Those ODM sales drove only 12.8 percent of revenues in the quarter, which means these large scale customers are paying a lot less for storage than their enterprise peers.

How much less? If you do the math on IDC’s storage numbers, those buying storage gear in the first quarter of 2013 from the ODM suppliers paid an average of $119 per TB; those who did not buy from the ODMs paid an average of $875 per TB. Fast forward to the fourth quarter of 2014 and those buying ODM storage gear paid around $90 per TB, compared to just under $550 per TB for those who did not buy storage from the ODMs. That is a big gap even if it is lessening.

“The question that vendors have to ask themselves is do they really want to go after a business that is 10 percent of the revenues but which drives 40 percent of the capacity,” Sheppard explains. “Some do, and some want to build their own clouds to provide storage services directly.”

Sheppard does not want to give the wrong impression about the storage business. He says that the traditional storage array makers are also growing and turning a profit. He says that companies that are offering scale-out file and object storage, or delivering flash-based products, are able to find growth. It isn’t a matter of the ODMs showing all of the growth at all. They are just driving the biggest revenue and capacity gains.

Be the first to comment