We have a saying around here at The Next Platform, and it is this: Money is not the point of the game. It is just the way that you keep score.

As entrepreneurs ourselves, this is not meant to be a flippant statement, and we fully realize that it is the corporate entities and public organizations of the world that give jobs – and therefore a substantial portion of the meaning of life as well as a means of subsistence to people. The more money you make, the more people you employ, the more lives you sustain.

There is profound honor in that, and it is its own network effect and perhaps as important as the network effects of partner ecosystems and software ecosystems and volume economics that companies like IBM, Digital Equipment, Microsoft, Intel, Apple (in consumer products but it could do datacenter in a heartbeat if it chose to), and now Nvidia have mastered over their various decades.

A titan always rises as the other ones hang around living off their legacies, and if they are lucky the titans make it through one or two industry phases, sometimes more.

IBM has done better than that, for instance. Big Blue has evolved from a maker of tabulating punch card gear to a hodge-podge of meat slicers, weight scales, time card machines, and tabulators to electronic calculating machines aimed at integer and floating point data to relatively high volume minicomputers that democratized mainframe-style computing to a maker of PCs and an active (if hesitant) participant in the client/server and e-commerce and Internet revolutions to something of a software and services behemoth that lives off those legacies. IBM is trying to build a new legacy based on distributed computing and Linux. But it is helpful sometimes to remember that IBM’s roots go back to Herman Hollerith’s tabulating machines used to compile and analyze the 1890 census in the United States. They’re deep. Profoundly so.

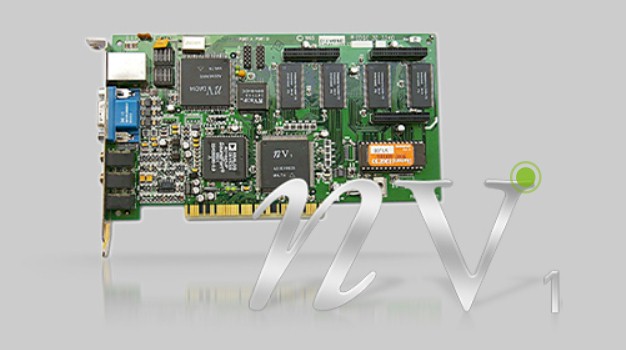

Nvidia’s roots go back to Jensen Huang being a director of engineering at LSI Logic and a CPU designer at AMD, and being frustrated with the lack of 3D graphics in games. And in 1993, on the day he turned 30, Huang teamed up with Chris Malachowsky and Curtis Priem to found the company he still runs. The “n” in nVIDIA is a variable as much as it implies “enabling video.” Perhaps these days the company should be called nCOMPUTE-with-nETWORK or maybe simply nDATACENTER, to be consistent with the font of its original logo. (That’s the last time we will type Nvidia that way.)

The NV1 video card came out two years later, in 1995, shown above, and the company has been a hell-raiser ever since.

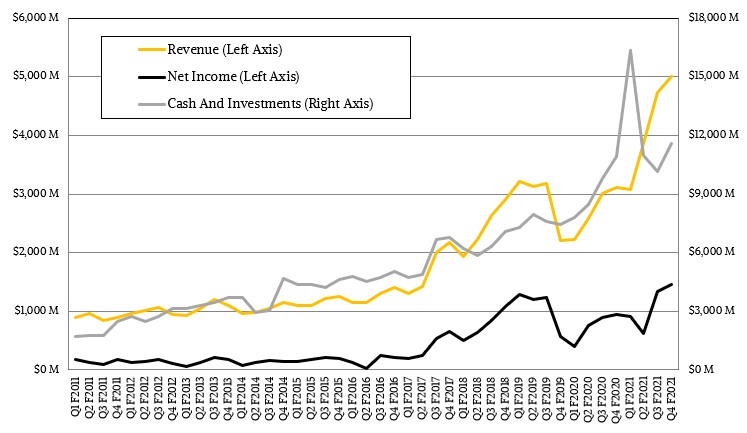

When we look at Nvidia’s most recent financial report, for its year-end of fiscal 2021, we are obviously impressed with the change that has been wrought by Huang’s vision and Nvidia’s engineers over the past decade and a half since GPU compute came into being. And we can’t help wondering just how far this vision of the datacenter that Huang is piecing together and what the score of this game – a kind of Mindcraft built of contemplation, concentration, chips, code, and cash – will be when another decade goes by.

The funny bit is that from its very beginnings, IBM had the aspiration to be the data processing giant it eventually did become, and Nvidia, by Huang’s own admission, was an unintended force in super-scale parallel compute that has extended its visualization engines from HPC compute into database acceleration, machine learning, data analytics, and heaven only knows what next. Software writing software is the main theme, and that knows no boundaries as we normally have when we lay our Cartesian planes on top of markets to carve them into boxes so we can make sense of them.

From a hardware perspective, Nvidia wants to be a much bigger player in how the datacenter is transformed into the new computer, something we talked with Huang about at length in April 2020 in the wake of the $6.9 billion acquisition of InfiniBand and Ethernet switch chip and device maker Mellanox Technology and then again in October 2020 lots more detail in a video interview with Huang in the wake of Nvidia’s proposed $40 acquisition of Arm Holdings, the steward of the Arm chip architecture, which was announced in September 2020. Nvidia has said from the beginning that the Arm acquisition would take around 18 months to wind its way through the antitrust regulatory bodies of the world, and in a call with Wall Street analysts to go over the financials for the quarter and year ended in January, Collette Kress, chief financial officer of the company, said that “the process is moving forward as expected” and that Nvidia was “in constructive dialog with the relevant authorities” and is “confident that regulators will see the benefits to the entire tech ecosystem.”

We take Huang at his word that Nvidia wants to be a good shepherd of Arm technology and is interested not only in making its own devices, but keeping the current licensing model that has made the Arm architecture the go-to instruction set for embedded and IoT devices, smartphones, tablets, and an increasing number of PCs and servers. Arm Holdings is a network effect in its own right, and as we pointed out before, it really doesn’t make very much money and is not, in and of itself, a big revenue generator. As a licensor of technology, it does great, But the 500 or so companies downstream from it make a hell of a lot more money than Arm does – top and bottom line. (We think of “make money” as revenue and “keep money” as net income. And honestly, if you are keeping score, it is “keep money” that matters as much – since this is the investment in the future – as “make money” – which is the stuff you use to give people jobs and therefore economic life. We never liked the term “make money” to mean income.)

To figure out where Nvidia might be going, let’s first talk about where it has been and where it may be headed in the future.

In the quarter ended in January, Nvidia’s revenues were up 61.1 percent to just a tad over $5 billion, which was a record quarter, and net income rose by 53.4 percent to $1.46 billion, also a new record level for profits. Nvidia increased its cash hoard to $11.56 billion, up by $1.42 billion, and every little bit gives it more maneuvering room to do the Arm deal.

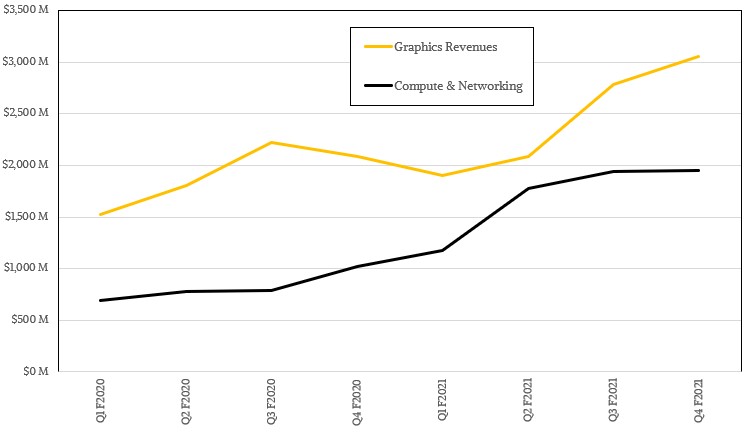

Last year, Nvidia started a new classification for its sales, which broke its business into a Graphics group and a Compute & Networking group. For some reason, the operating income for these two units were not reported as has been the case for the prior three quarters and their year-earlier compares (so six quarters in total), which is odd. And Nvidia has not yet filed its 10-K report with the US Securities and Exchange Commission, so we can’t see if it is there. Hopefully this will be updated soon.

In any event, in the final quarter of fiscal 2021, Graphics group sales rose by 46.6 percent to $3.06 billion. Compute & Networking group sales rose by a stunning 90.7 percent to $1.95 billion – and that was with a pretty sizable decline in sales of Mellanox networking stuff in the quarter.

Based on the fact that Kress said Mellanox sales were up 30 percent from the third quarter of 2019 when Mellanox was an independent company still, that puts Mellanox revenues at $494 million, which is a 19.6 percent decline from the $614 million in sales in Q3 F2021, which had a big bump in sales from an unnamed OEM partner in China that we think could be Huawei Technologies but possibly Inspur or Sugon building hyperscaler or supercomputing equipment. By the way, Nvidia said going forward it would not be providing any specific information about Mellanox sales, so there goes that insight, which helps us break networking from GPU compute in the Nvidia financials. And once again, we lament the fact that Mellanox, which gave excellent and detailed financials that allowed you to really understand technology transitions, is no longer providing such detail. If anything, Nvidia should be helping us understand the adoption curves by revenue streams for its gaming, professional visualization, and datacenter compute, and even breaking GPU compute into HPC, AI training, AI inference, and other buckets while we are at it. Why not? There is no law against being precise. It is ever the way of large companies to get ever more opaque.

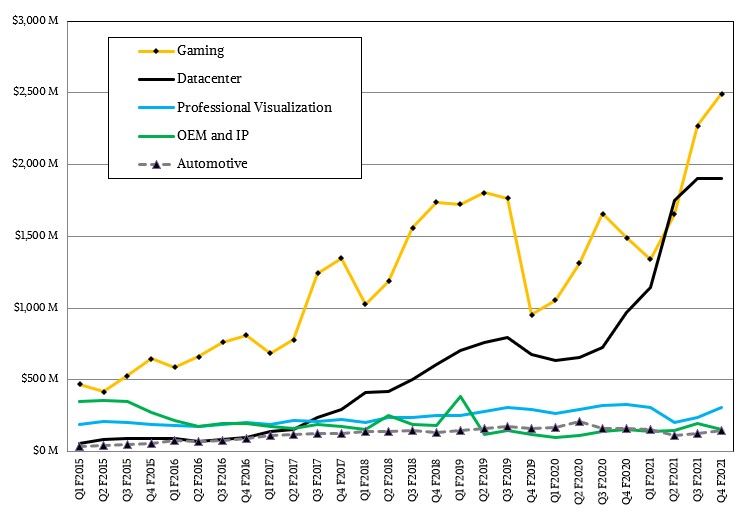

Nvidia is still providing the breakdown in sales by groups it started doing in fiscal 2015 when GPU compute in the datacenter and in the automotive sectors first became material.

In the quarter, the Datacenter group posted sales of just over $1.9 billion, up 96.6 percent, and again that is with a pretty substantial decline from the Networking division that was formerly known as Mellanox. (Mellanox revenues were not in the Q4 F2020 numbers, remember, so the compare is quite a bit easier year-on-year.) If we back out Mellanox revenues from the Datacenter group, then the core GPU compute business in the datacenter space from Nvidia rose by 45.6 percent to $1.41 billion. While hyperscalers and large public cloud builders continued their ramp of deployments of “Ampere” A100 GPU accelerators in fiscal Q4, growing sales both year-on-year and sequentially from fiscal Q3, Kress said that its “vertical industries,” meaning everything else but particularly in HPC supercomputing, financial services, higher education, and the consumer Internet verticals did well. (We would assume that most of the sales into higher education were for what we would call HPC/AI, but there is some stratification here based on size, obviously.) In any event, everything not hyperscaler or large public cloud accounted for “well over 50 percent” of daracenter compute sales, which is noteworthy and probably a first.

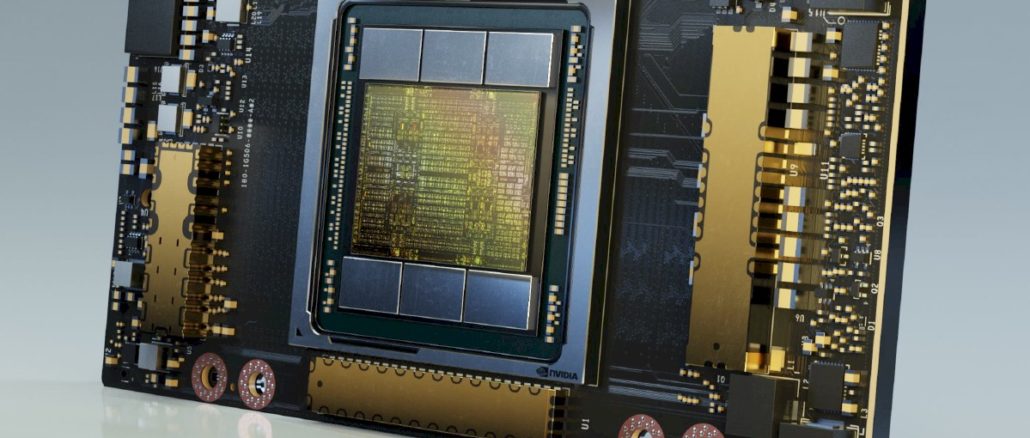

Both Kress and Huang said time and again on the call with Wall Street that the A100 ramp was just getting started, and Kress said it was a smoother generational transition than prior GPU accelerator ramps and had better visibility also. Huang added later in the call that A100s would be sold for “a couple of years of continued growth.” That doesn’t sound like a hypothetical “Einstein” or “Heisenberg” or “Bohr” GPU is on the horizon, and we made those names up so don’t go thinking we know something about the future Nvidia roadmap. The days when Nvidia put its roadmap put there as a five year plan with codenames and features are long gone. Especially with Moore’s Law probably blowing out the tires at 5 nanometers and slamming into the guard rails of physics at 3 nanometers.

The details on what is happening inside the Datacenter group were a bit thin for our liking. Kress said that datacenter sales would grow in Q1, as would all of the other lines of business shown in the chart above, and Huang added that Mellanox switch sales grew by 50 percent year-on-year in Q4 F2021, which is pretty good for Mellanox and shows that whoever stocked up on Mellanox gear in China last quarter probably bought some ConnectX cards or ASICs and maybe some switch ASICs. Huang said that both Ethernet and InfiniBand would grow in the coming fiscal 2022 year, and added that the “BlueField” DPUs would start taking off and that in the span of maybe five years or so, all servers would have DPUs of some sort because servers need hardware-accelerated virtual I/O and storage and they need to get security off of the same control plane and data plane as the applications running on CPUs – something everyone seems to agree on among the hyperscalers and cloud builders at this point, and we also agree as our coverage of SmartNICs and DPUs illustrates.

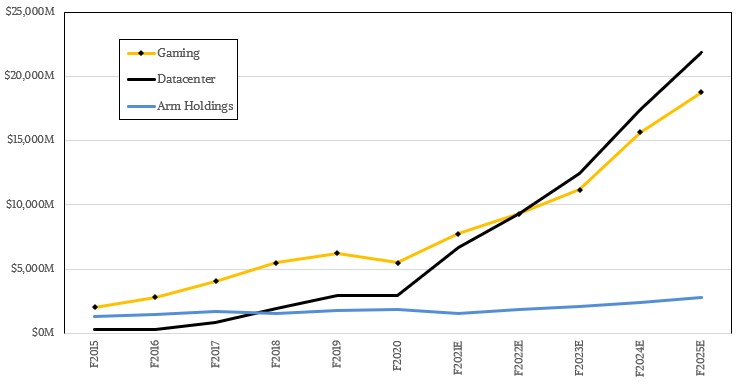

Now, let’s talk about the future and let’s talk about it on an annualized basis because sales are lumpy on a quarterly basis in a lot of Nvidia’s markets at this point. After a dip in fiscal 2020 (which was mostly calendar 2019, and had more to do with product transitions than anything else), Nvidia was up like crazy in its Gaming group and with the addition of Mellanox grew its Compute & Networking group by an even faster rate. If current trends persist and growth rates cool a bit for both halves of the Nvidia business, we think revenue streams for these two groups at Nvidia will meet somewhere this fiscal year. If you assume 20 percent growth for Gaming group and 40 percent growth for Compute & Networking, which sort of fits the past pattern of hypergrowth and then a cooling to crazy growth, and especially considering that Nvidia, like other chip designers and sellers at the high end is supply constrained and cannot fully meet demand on any fronts, then Gaming will hit $9.31 billion in sales in fiscal 2022, and Compute & Networking will hit $9.37 billion.

If gaming holds at 20 percent growth for a couple of years bit a bump in fiscal 2024 for a new generation of GPUs against an even larger gaming market, then the Gaming Group will be at somewhere around $19 billion in sales at the end of our Nvidia forecast into fiscal 2025. We think the growth rates for Nvidia’s Compute & Networking group will be even higher, but follow a similarly sine wave and will kiss $22 billion by the end of the forecast.

All of this is without the deal Arm Holdings being completed and does not include Arm revenues at all. But just for fun, we plotted Arm Holdings revenues per year against the closest year in the Nvidia calendar, and then plotted out 15 percent annual growth from 2021 through 2024 (calendar) and F2022 through F2025 (fiscal).

This blue Arm line in the chart above does not take into account the offset for the January month in Nvidia’s fiscal year, which we have no idea how to break out by brute force. This is just to illustrate the principle that Arm Holdings will not add much to the Nvidia revenue stream. But, we do think that Nvidia will have to not only hit its impressive goals for a hybrid CPU-GPU implementation of the DPU, but will also have to roll out its own CPUs if it hopes to meet those Compute & Networking group targets that we have set in the model above.

Nvidia may be able to say it doesn’t believe in FPGAs, but there is no way that the market does not want Nvidia to make an Arm server CPU. And, the good news is that it can do that, and we think do it well, without closing the deal for Arm Holdings. Owning Arm Holdings and driving that licensing model into other Nvidia products is a bonus, and there is also nothing stopping Nvidia from licensing its GPU, switch, and network interface ASICs to the world, too.

The possibilities are still open, with or without control of the Arm architecture. And that deal is being done with stock and not a lot of cash, so it is a good use of market capitalization as far as we are concerned. Ditto for the $35 billion deal for AMD to buy Xilinx. We could argue the finer points and pluses and minuses of either deal, but we concur that Nvidia and AMD should be spending the market cap to do big things while they can. It’s all Monopoly money propped up by our 401(k) retirement plans and faith in the future – and hopefully it doesn’t look like real antitrust monopoly money to regulators. Either way, if current trends hold, Nvidia will have a datacenter business that is as large as that assembled by IBM and Intel and Microsoft. No mean feat, that.

love the way you think TPM

Thanks. I hurt my own head sometimes synthesizing. My brain is a bit like a 33 MHz 486 that is overclocked. There ain’t no massively parallel A100 in here….

33MHz 486 ? You need to upgrade to a 40 MHz Motorola 68040 my friend ! Then your brain becomes a rocking Amiga 4000 !!