With much of the world in lockdown because of the coronavirus pandemic, it is not a surprise that much of the attention that is being paid to Amazon’s financial results for the first quarter of 2020 focused on its online retail operation, which is literally a lifeline to many in the United States, and the massive warehousing and shipping infrastructure behind it. In one story in a major financial newspaper, the Amazon Web Services cloud computing business unit was not even mentioned once.

That’s just plain weird.

It’s not our job to track and comment on the e-commerce, entertainment, electronics, and other businesses at Amazon, but we most certainly are keenly interested in what is happening at AWS as the pandemic kicked in during March and continues to cause issues and create opportunities.

At the moment, nothing looks too much out of the ordinary from the topline and middle lines at AWS, as far as out eyes can tell. Things seems to be balancing out, just as Brian Olsavsky, chief financial officer at Amazon, explained in a recent call with Wall Street analysts going over the numbers.

“What we are seeing post-COVID varies by industry,” explained Olsavsky. “We are a bit well positioned in that we have such a breadth of customers. There are millions of active customers from start-ups, to enterprises, to public sector. So there’s a lot of variance. And again, in what individual industries are seeing right now, things like videoconferencing, gaming, remote learning, entertainment all are seeing much higher growth and usage. And things like hospitality and travel certainly have contracted very severely, very quickly. So, I think there’s going to be a mixed bag on industries, and of course this is will be tied to general economic conditions for the country and the world, quite frankly. So right now, we want to be there for our customers. We want to be able to scale up when they need us. We want to be there and support them regionally around the world. And we’ve been doing a good job at that, I believe.”

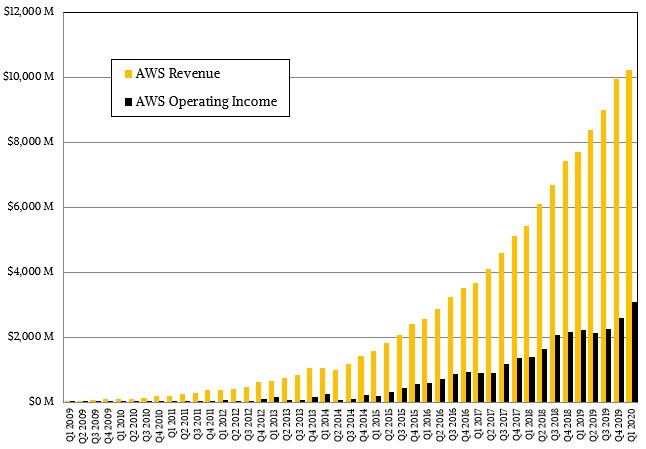

In the quarter, AWS revenues were $10.22 billion, up 32.8 percent year on year and up 2.6 percent sequentially. That is a little bit less than the sequential growth of 3.5 percent that AWS saw this time last year, and a lot less than the 7 percent to 10 percent (rounding a bit) sequential growth it saw in the other three quarters of 2019. Operating profit for AWS came to $3.08 billion, up 38.3 percent and represented 30.1 percent of revenue, a slightly higher portion of the revenue than last year and not too shabby for an IT vendor that designs its own iron and systems software, has that iron manufactured by specialist at cut-throat prices, and runs it as a service bureau for others.

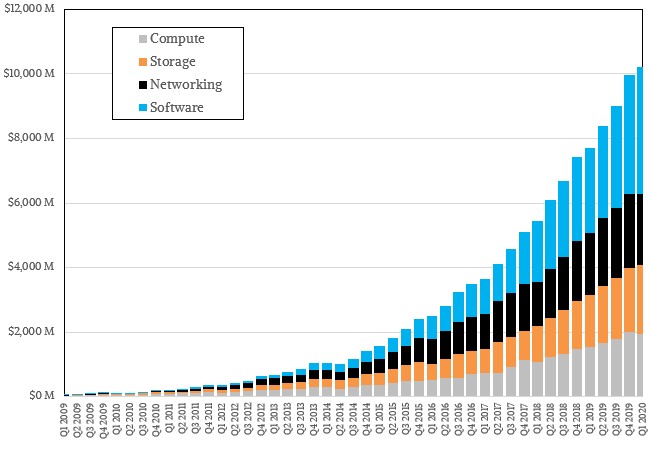

AWS doesn’t split its revenue stream down by the four horsemen of the on-premises datacenter apocalypse – Compute, Storage, Networking, and Software – but we take a stab (really not more than an informed guess that could be considerably off) at coming up with how AWS sales break down every quarter in the hopes that AWS will respond at some point and give us a few datapoints to build a better model. (That’s how this game works, Jeff and Andy. You are formally invited to play.)

It is up to the customers to consume the compute, storage, networking, and software that AWS builds (and its software partners also sell) to do the digital transformations and modernizations they need to do on their applications. It is, as Olsavsky said, up to AWS to have the most functionality, to maintain the largest and most vibrant community of customers and partners, to have proven operational and security experience, and to build new capabilities like machine learning and artificial intelligence that will help customers move into the future. The company knows its job, and it does the same thing for the other Amazon businesses that it does for over a million other companies.

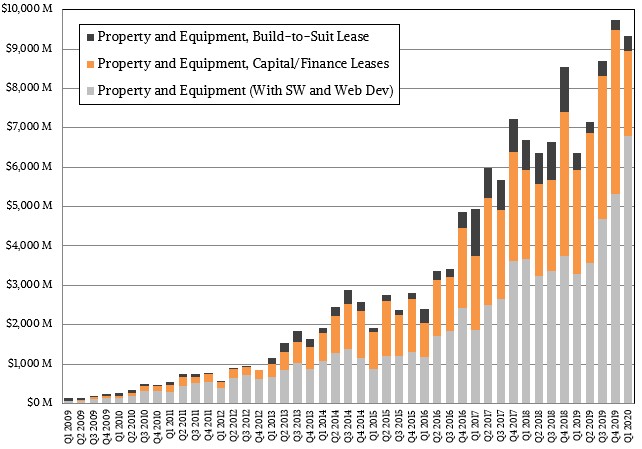

As for its own profitability, Olsavsky added that AWS booked an $800 million benefit from extending the useful life of its servers (meaning it didn’t spend $800 million it would otherwise have had to put into capital equipment costs) by keeping them in the field longer. Olsavsky did not give a before and after number for the term in the field, but he did say this was both a hardware and a software challenge and this benefit would roll through the coming quarters as more of the base was kept around longer. We will try to figure out what AWS is doing and how. . . . Stay tuned, but don’t expect much cooperation from AWS, which is among the most secretive companies in the world. We suspect that the “Nitro” SmartNICs, which offload virtual compute, networking, and storage functions and free up cores for application compute, have a hand in this, as does downcycling boxes from core compute to maybe cold storage does as well.

AWS overall had sales of $75.45 billion, up 26.4 percent, and operating income fell by 9.8 percent to $3.99 billion. Net income was $2.54 billion, down 28.8 percent and hurt, in part, by the $600 million in costs associated with changes to the online retail business in the wake of the pandemic outbreak. If you back out AWS from the overall Amazon numbers, the “real” Amazon business of consuming and entertainment had $65.233 million in sales, up 25.4 percent, but operating income was down 58.4 percent to $914 million.

That’s another way of saying that if AWS had not figured out a way to stretch the lifetime of its servers in the field in Q1 by $800 million worth of capacity it did not buy, the overall Amazon would have seen an even smaller net income. This effect will probably not be enough to keep Amazon from going into the red during the second quarter of this year of Amazon has to book $4 billion in COVID-19 costs as it expects – unless AWS plans to cut its server spending by as much to compensate. For all we know, that’s the precise plan – buy iron on the cheap in Q3 and Q4 of 2019 and now again in Q1 of 2020, and slam on the brakes extra hard – much harder than anticipated thanks to the COVID-19 costs and definitely engaging the antilock braking system – on server spending in Q2 and probably Q3 of 2020 to help cover some of those COVID costs.

This is precisely how most IT organizations behaved when the Great Recession hit in late 2007 and accelerated in 2008 and into early 2009. Big iron machine deals finished up, and X86 iron sales fell off a cliff by 35 percent or more each quarter and came back around when server virtualization features in the chips made a compelling case for upgrades. If the Great Infection persists and spending on iron is severely curtailed, we would not be surprised to see companies start throwing out server virtualization hypervisors and moving to converged container and VM systems, like OpenShift running KubeVirt. They are going to need to stretch the life of their iron by dumping heavy hypervisors, or at least getting off the CPU cores as AWS has done with Nitro.

Is the Graviton2 deployment officially behind schedule?