The market for servers used to be a lot more predictable in the past, with a portion of the tens millions of companies worldwide buying machinery in their own cycles that more or less coincided with the global gross domestic product. Now, chip makers like Intel are enjoying the benefits of the vast amount of infrastructure investment that hyperscalers and cloud builders are doing, but when they pull back on the reins at the same time that enterprises also take a pause, this causes problems.

It is a good problem to have, especially if you look at how well Intel’s Data Center Group, which makes server processors, chipsets, motherboard, and sometimes systems, did in 2018 – despite a slight downtick in revenues and a flattening of profits in the final quarter of the year. With AMD bringing out its second generation “Rome” Epyc processors within a few months, and the “Cascade Lake” Xeon not generally available to enterprises until the first quarter was over, we were not expecting the first quarter to be a gangbuster one. People want to see what the future holds with the 10 nanometer “Ice Lake” Xeons that the hyperscalers and cloud builders, and perhaps a few HPC centers and large enterprises, will get their hands on before years end and they also want to see how the Rome Epycs will stack up. There are those who are also considering IBM Power9 processors and perhaps an Arm server chip from Ampere or Marvell.

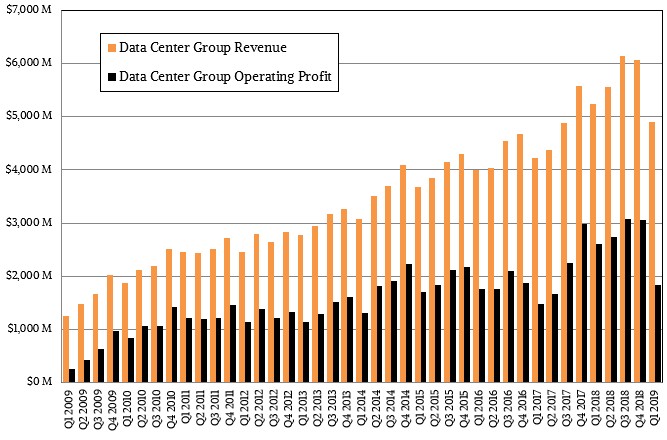

The is the first big decline in quarterly sales that Intel has endured since the first quarter of 2012, and that one was relatively small by comparison. Back then, the market was waiting for the delayed “Sandy Bridge” Xeon E5 processors, which launched on March 6 of that year, with only three weeks left in the quarter, and as now, the market took a pause. In this case, that pause pushed down Intel’s Data Center Group revenues by four-tenths of a percent to $2.45 billion and its operating profit down by 6.5 percent to $1.14 billion. This time around, only seven years later, the hyperscalers and cloud builders have doubled their share of Intel’s datacenter chip pie, and when they slow down, it hits Intel harder. But again, there is so much more money sloshing around that Data Center Group is a lot bigger, at $4.9 billion in sales and $1.84 billion in operating income.

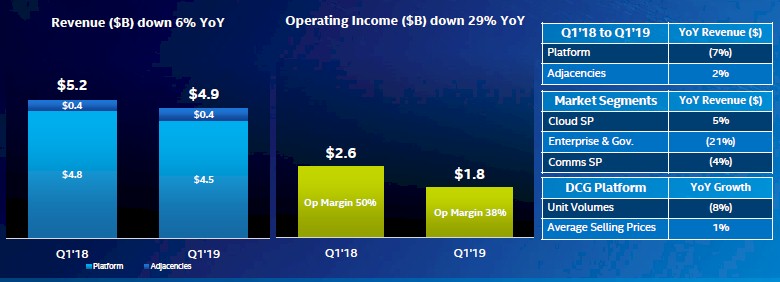

That doesn’t sound too bad until you do the math. In the first quarter of 2019 ended in March, Intel’s Data Center Group saw revenues drop by 6.3 percent – an order and a half magnitude more than back in 2012 with the pause going over Sandy Bridge – and operating income has dropped by a stunning 29.2 percent year on year. This is due to Data Center Group having to pick up some of the development and production costs associated with the 10 nanometer process that will be used to etch Ice Lake chips for clients, servers, and other devices. The clients are expected to get Ice Lake Core processors by the holiday season, and newly appointed chief executive officer Bob Swan, formerly the company’s chief financial officer, said in a conference call with Wall Street analysts last week that the first Ice Lake part would be qualified – meaning tested for commercial readiness – in the second quarter. Swan added that Intel was raising its production goals for its 10 nanometer chips for 2019, which is good news for the company if it can keep up with product demand – something it was not able to do with low-end PC parts at the tail end of the 14 nanometer era that was admittedly prolonged by years because of delays getting 10 nanometer manufacturing up to snuff.

The dip that Intel experienced was not just limited to its Data Center Group. Intel’s flash memory business was also impacted as both DRAM and flash memory prices are starting to come down, as they always do. So the data centric parts of Intel’s business – as opposed to its client centric parts where it sells chippery for desktop and laptop PCs as well as for other kinds of client devices – also took a hit. The situation was not helped by the low-grade trade war going on between the United States and China, which kit revenues across the board at the company.

“Our conversations with customers and partners across our PC and data centric businesses over the past couple of months have made several trends clear,” Swan explained on the call. “The decline in memory pricing has intensified. The datacenter inventory and capacity digestion that we described in January is more pronounced than we expected. And China headwinds have increased, leading to a more cautious IT spending environment. And yet those same customer conversations reinforce our confidence that demand will improve in the second half.”

Drilling down into the results for Data Center Group in the first quarter, volumes across CPUs, chipsets, and everything else Intel counts by units were down 8 percent year on year and off 17 percent sequentially from the fourth quarter of 2018. Intel had a 3 percent sequential decline in shipments the fourth quarter of 2018, but average selling prices were up 2 percent as customers inched up the SKU stack for Xeon processors. That sequential decline was noteworthy, but on an annual basis, unit volumes were up 9 percent and ASPs rose 1 percent, but that growth was less than the general sawtooth trend we have seen for years with Data Center Group.

In the first quarter, sales of core Data Center Group components were off 7.1 percent to $4.48 billion, while adjacent products, such as Ethernet adapter cards, Omni-Path network switches and adapters, silicon photonics, and we presume custom systems, rose by 2.4 percent to $420 million. Add it all up, and Data Center Group had $4.9 billion in sales, and as we already pointed out, off 6.3 percent year on year. Intel’s overall sales were flat at $16.06 billion, operating income was off 6.6 percent to $4.17 billion, and net income dropped by 10.8 percent to $3.97 billion. Just to give you a compared to what.

The drop in spending by enterprises and governments was dramatic. Not quite as bad as the 30 percent to 35 percent power dive we saw during the first few quarters of the Great Recession, but close enough to cause not just eyebrows but more than a few pulses to rise. While hyperscaler and cloud builder revenues – what Intel calls cloud service provider – grew by 5 percent, sales to communications service providers (meaning telecommunications companies and other Internet service providers) fell by 4 percent. Revenues from customers in the enterprise and government sector – meaning everyone that is not a service provider in some fashion, which Intel tracks diligently and thoroughly – fell by 21 percent. Here is to hoping that is not some sort of leading indicator. . . . That would be a bad one. For now, Swan and his team are attributing this to an inventory correction.

In the adjacent markets that are part of the broader data-centric business segments (whose products are aimed at client as well as datacenter devices), sales were mixed. The IoT Group actually grew by 8.3 percent to $910 million with operating profit of $251 million, up 10.6 percent. But the Non-Volatile Storage Group had a 12 percent decline to $915 million, and losses ballooned by a factor of 3.7X to 297 million. The Programmable Solutions Group, which makes FPGAs and related products, posted a 2.4 percent decline in sales, to $486 million and operating profits were off 8.2 percent to $89 million. At least this Altera business has been adding to the middle line for the past four years.

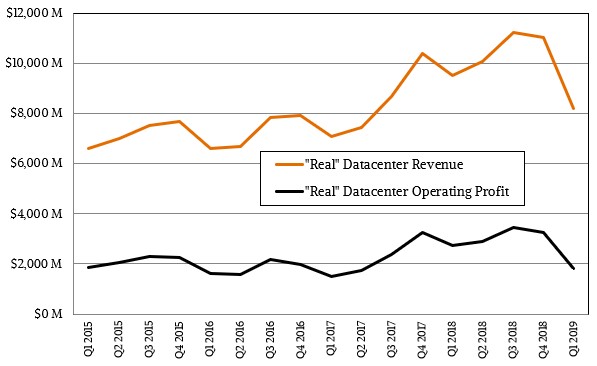

We like to try to suss out what Intel’s so-called “real” datacenter business looks like in terms of revenues and operating profits, and this includes the actual Data Center Group numbers plus the portions of the IoT, NSG, and PSG portions of Intel that we reckon are really going into the datacenter and not into client, mobile, and other devices. We only have data on this going back to 2015 because that was when Intel started providing more granularity on its adjunct businesses. Take a look:

By our estimates, Intel’s real datacenter business was down by 5.9 percent to $6.41 billion, and operating profits were down by 33.6 percent to $1.81 billion. The confluence of the flash downdraft, the 10 nanometer ramp, and the slowdown in chip buying for servers is hitting Intel pretty hard. And the competition has not really ramped up yet from AMD, IBM, Marvell, and Ampere on the server front. That is coming, though.

Looking ahead to the rest of 2019, Swan chopped Intel’s overall revenue projection to $69 billion, a 3 percent decline compared to 2018. The data centric parts of the business, which includes Data Center Group but is not limited to it, are anticipated to shrink in the “low single digits” and Data Center Group down “mid-single digits” year on year. So much for that 15 percent per year growth rate Intel was telling Wall Street only a few years ago. Data Center Group, said Swan, is being pushed down by a tough compare, continued weakness in China, capacity absorption (mainly by hyperscalers and cloud builders), and channel inventory. Swan added that he expected “incrementally more challenging” pricing for flash memory in 2019, too, adding to Intel’s woes.

That canary in the coal mine that is probably going to be fine, unless there is an actual recession. But that pretty little bird is no doubt feeling a little sleepy.

“People want to see what the future holds with 10 nanometer”.

Absolutely, there’s plenty of good commercial product to chose from in the pantry of the secondary market; Intel Xeon v3/v4 and AMD Epyc Naples and TR 29xx, no matter what Xeon generation platform your operation is upgrading from.

Everything finds its way back to reuse in secondary market. Hand me down and step me up is the way compute procurement has always been.

Westmere 6/8/10 cores, 69,403,106 units of production

IB v2 availability 495,587,100 units of processor production.

HW v3 availability 648,148,380 units of processor production.

BW v4 availability 368,138,250 units of processor production.

Scalable Skylake 43,250,159 units of production

Everyone can afford to wait the adoption and adaption considerations of 10 nm & < ?

Has always been a question between the considerations of utility value, operation effectiveness, efficiency, competitive and financial advantage, and greed.

"Recession"?

Intel obsoletes all of v3/v4 in in one next short run and that's more like the catalyst for an economic depression.

Next platform generation if you need all that network processing bandwidth is going to be an enormous upgrade cycle.

Mike Bruzzone, Camp Marketing

That canary in the coal mine that is probably going to be fine, unless there is an actual recession

Still with the TR(Threadripper) nonsense and that’s not really a plausible choice in the using of Threadripper/TR4 CPU/Motherboard platforms for professional production workloads with any hardware that’s not really vetted/certified for ECC memory usage even if the hardware “Supports” ECC at some untested/unvalidated level.

That’s in the form of insufficient amounts of QA/QC and proper vetting/Certification on any Consumer/HEDT(High End DeskTop) SKUs for any professional level workloads that have to be as error free as possible and must be running on Server/Workstation hardware and firmware that’s been fully tested vetted/certified for ECC memory usage, a more costly process that consumer CPU/MB OEMs do not take with any of their non professional branded offerings.

AMD appears to be getting its Epyc/Rome SKUs to market in Q3 of this year and the ramp-up for server SKUs takes longer than any consumer CPU variants. AMD really needs to also consider its first generation Epyc/Naples products and what value added features still remain from that Processor/Platform that has less than half of Epyc/Rome’s FP AVX capabilities among other more advanced metrics that the Epyc Rome/MB-Platform will offer over Epyc/Naples.

And AMD’s newer(Nov 2018) Epyc/Naples higher clocked/higher frequency 16 core Epyc/Naples 7371 variant is a good example of AMD still being able to obtain a higher tiered/higher ASP segment using higher clocked/higher binned Epyc/Naples parts that target the workstation/server market segments that can benefit more from higher processor clock speeds for their specific workloads.

AMD’s higher ASPs are what is getting that 41%(Q1 2019) gross margin metric and even though AMD’s revenues are down somewhat some of that revenue decrease can be cyclical in nature and semi-custom division related, Blockchain related also for both AMD and Nvidia! But higher gross margins are necessary to increase profitability now and in the longer term, and for revenue increases also.

Intel’s 10nm problems has sure had them tweaking their 14nm process past the point of diminishing returns and any higher clocked 14nm parts on 14nm+++++ are sure to be more inclined to run into power usage issues compared to 10nm/7nm processes. And Intel’s 10nm is still not going to be fully covering the consumer markets above mobile this year and server/10nm is even longer range there for the obvious reasons.

If I where AMD I’d readily consider what even lower cost server market segment that I could slot the lower clocked and oldest Epyc/Naples server/workstation variants into while introducing more higher clocked Epyc/Naples variants like the 7371 16 core variant that comes with a higher ASP. So some 24/32 core Epyc Naples variants at higher clocks and higher ASPs and the older lower clocked Epyc/Naples offerings discounted and slotted in against Intel’s lower cost Xeon variants where Intel can not match AMD’s Epyc/Naples and that SP3 MB Platform’s 128 PCIe 3.0 lanes and 8 memory channels per socket and other feature sets that Intel charges too much for relative to what AMD’s offers at no extra charge.

The Professional Workstation/Server Parts and their extended warranties and product availability guarantees are also part of the cost/benefit analysis that the server clients will take into consideration at usually 3+ years for Server/Workstation CPUs and Motherboards also. Added in there is the extended levels of support for things like firmware and such from the server/MB OEM’s and that can not ever be matched by any consumer grade parts that have much shorter warranty/support periods and consumer CPUs are made obsolete rather quickly and those consumer grade parts have no guaranteed extended availability periods from their makers.

You do profess to be in marketing to some degree but it’s not in a technically server market related manner from the many errors you still appear to be making. Maybe your market analysis is more related to that of the supply channel related metrics analysis angle that’s not as related to the actual technology side of things. So things like the velocity of product movement in and through the supply channels is not as very much related to newer and future products and their relative competitive natures that the server/workstation clients go through greater pains to suss out when multi-million purchase orders are in consideration. The cost/benefit analysis figures in greatly and that includes Warranty and other factors like periods of product support and product availability as well as power usage and cost/features among other factors related to the TCO in the server market.

Intel will have to match AMD’s price/feature metrics as well as Price/Performance metric and Intel does have some Optane related IP that AMD currently can not match. Intel also has in-house FPGA(Altera acquisition) related IP that AMD currently lacks as an in-house developed option. AMD has to partner with some third party FPGA maker for that IP currently but AMD does have a more advanced GPU/Accelerator IP for compute/AI related usage in addition to discrete graphics usage where Intel is now just getting started in the discrete GPU market somewhere in the 2020/later time frame.

The server market also includes OpenPower Power8/Power9 and Power10 incoming in 2020. The custom ARM servers(Thunder X2/etc.) also for an even lower cost market segment even relative to AMD’s x86 offerings. The OpenPower Power offerings will be mostly upper and middle market range for the time being but there are low cost power9 Talos II and Raptor systems offerings also being tested that are even of interest to some home server users.

Power9 is more interesting for its SMT4 offerings in addition to the Power8/Power9 SMT8 offerings. So the higher core count SMT4 Power9 variants are better able to compete with AMD’s and Intel’s SMT2 x86 variants where some workloads may benefit from more physical cores rather than virtual cores. SMT4 appears to be the all around server workloads sweet spot for Power8(Configurable SMT) and the Power9/SMT4 variant that has more actual physical cores with lesser SMT hardware(Only SMT4 in the hardware but higher actual physical CPU core counts).

Potential server/workstation clients really take into consideration their respective intended workloads first among the other factors while their bean counters will always be crunching the upfront costs and the financing of it all to figure out the TCO over the longer run where power usage plays a larger role along with other factors that affect costs. Software Licensing on a per-core or per socket basis will also play a role in the purchasing decisions among any server/services providers that will be relying on third party OS/Software packages.

That’s a lot more to consider along with any CPU Processor/Motherboard platform benchmarking performance and feature-sets/dollar analysis and other metrics.

The Canary That’s The Bean Counter is the more plausible description.

I understand your point, have been making it for months and appear well informed, this contribution.

“Still with the TR(Threadripper) nonsense and that’s not really a plausible choice in the using of Threadripper/TR4 CPU/Motherboard platforms for professional production workloads with any hardware that’s not really vetted/certified for ECC memory usage even if the hardware “Supports” ECC at some untested/unvalidated level.”

But you Still have not been able to provide a list of TR ECC validated kit on spec from design manufacturers and producers who must be many I don’t have time to address that so I volunteer you.

Zeppelin dice support ECC its up to AMD, mainboard, control hub, memory controller and memory suppliers to state certification. And until someone can prove they do not . . . its ridiculous to think otherwise on competitive advantage difficult to duplicate?

Mike Bruzzone, Camp Marketing

Looking into chip set specification x399 has ECC support which MSI claims, on Epyc side that is TR there’s no difference, ASpeed AST 2500 has ECC option.

That took about 15 minutes to start the list. Which does not prohibit your own internal qualification.

mb

Obviously Power has always offered ECC support.

mb

Here’s a report on Epyc on chip memory controller offering ECC support.

https://www.faceofit.com/ecc-ddr4-ram-amd-epyc-cpu/

x399 offers ECC according to all the reddit hubbub on this ECC topic and ASPEED offers that option to main memory.

Thread ripper is Epyc. Epyc is TR. AMD global customer support rep in report needs an update; registered or unbuffered.

But I could not find at AMD.com the on-chip memory controller spec or its application notes. AMD apparently cant afford to produce all those ECC support stickers to distribute to board, controller / IP and memory compliments

Mike Bruzzone, Camp Marketing

“Now, chip makers like Intel are enjoying the benefits of the vast amount of infrastructure investment that hyperscalers and cloud builders are doing, but when they pull back on the reins at the same time that enterprises also take a pause, this causes problems. It is a good problem to have . . .

Replacement market whether todays adoption and adaption options or yesterdays step up;

v2 Xeon 495,587,100 processors produced looking for a second, third or forth home.

v3 Xeon 648,148,380 processors produced looking for a second or third home.

v4 Xeon 368,138.250 processors produced looking for a second home.

XSL 43,250,139 produced looking for XCL upgrade and then some.

It’s gonna be one hell’a of an upgrade cycle no matter what you’re stepping up to.

Mike Bruzzone, Camp Marketing