The secret to the longevity of any big corporation is a nearly constant process of reinvention. Those that can adapt to the times are the ones who survive, and one need only look at the recent and sad history of General Electric to see how quickly a stalwart contributor to the global economy can implode. Whether anyone likes to admit it or not, IBM is a company that is still more or less successfully adapting to the fast changes in the information technology sector. Although, we concede, it may not look like it from the financial results that IBM has turned in during 2018 and prior years.

Big Blue still has one of the largest systems businesses on the planet, and it is even more profitable, in terms gross profits as a percent of revenue, than the very large server, storage, and networking chip business that Intel has amassed over the decades, which is just a little bit bigger than IBM’s systems business. (The net effect is that they are both throwing off about the same amount of cash each year.) The comparison is a bit apples to orange, since Intel makes processors, chipsets, and motherboards while IBM does all of that and makes operating systems, middleware, databases, other software, and provides support and financing for systems on top of that.

This vast IBM systems business, which is anchored by its System z mainframes, which are at the heart of thousands of the largest organization in the world, and it is buoyed by its Power Systems business, which is for all intents and purposes the victor in the epic battle between Sun Microsystems, Hewlett Packard, and others in the open systems Unix server market that took place from the late 1980s until a few years ago. IBM won, but it won a market that has shrunk by a factor of 10X. But that sure beat losing the battle.

Nonetheless, the shrinkage in the RISC/Unix enterprise and HPC server space is why IBM has been pushing Linux so hard on its Power-based systems, to run everything from scale up in-memory systems like SAP HANA to scale-out clusters running various kinds of HPC simulation and modeling or data analytics workloads. Linux is, after all, the only operating system platform that is growing in the datacenter – Microsoft’s Windows Server has been seeing a decline for years as Linux becomes the preferred platform for new kinds of applications. This explains why Microsoft has embraced and extended open source software (particularly Linux) and why IBM is in the process of trying to buy commercial open source software distributor and Linux juggernaut Red Hat for a stunning $34 billion. IBM’s strategy is working sufficiently enough for the company to continue to invest in future System z mainframe and Power processors into the foreseeable future, but it wants a bigger piece of the systems software stack and Red Hat will give it that.

Let’s try to tease this systems business apart, because Big Blue sure does like to talk about its numbers in ways that hew more to the buzzwords of the day and that obfuscate the reality of its actual business. We will start with the fourth quarter numbers as reported and then do some guesstimating.

IBM has not been impressing Wall Street with dozens of quarters of revenue declines over the past several years, and the company once again had a 3.5 percent shrinkage in sales in the fourth quarter of 2018, at $21.76 billion. A lot of that is due to the strengthening of the US dollar against the foreign currencies of the countries where Big Blue does a substantial part of its business, and this is a common complaint for multinational behemoths. IBM had $10.68 billion in gross profit against this revenue in the fourth quarter, down 1.6 percent, and pre-tax income of $4.34 billion, down only eight-tenths of a point; it brought $1.95 billion to the bottom line, which was a lot better than the $1.05 billion loss it had a year ago after some writedowns.

In the fourth quarter, IBM sold $2.62 billion of systems hardware (which includes storage), off 21.3 percent compared to the prior year’s final quarter, which had a 71 percent increase in System z mainframe sales as the z14 generation of machines started rolling out in Q4 2017. IBM sold another $238 million of systems hardware to other divisions of the company, but this is an internal sale that is only used to calculate pre-tax profit for the Systems business. In any event, that mainframe spike a year ago was a tough compare indeed. The Power Systems business is comprised of scale out systems, which are sold in onesies and twosies to customers using IBM’s own AIX and IBM i platforms to host databases and back-end enterprise applications and which are also used in Linux clusters for parallel HPC and data analytics jobs, and scale up systems, which have from four to sixteen sockets in a single NUMA image and used to run very large databases and their enterprise applications for very large companies, much as System z mainframes are deployed. The Power Systems business showed growth in the first three quarters of 2018, and it did it again in the fourth quarter with 10 percent growth. The size of the Power Systems business and this growth is not even close to the growth of the overall systems market now and it is surely not enough to fill in the hole that is left as the mainframe cycle spikes up and comes down pretty fast.

But, a mainframe spike is better than not having one, and steady growth – even if it is modest – for the Power Systems business is a lot better than steady declines, which Big Blue has experienced for quite some time before really pushing Linux and shoring up its AIX and IBM i business on the hardware platform.

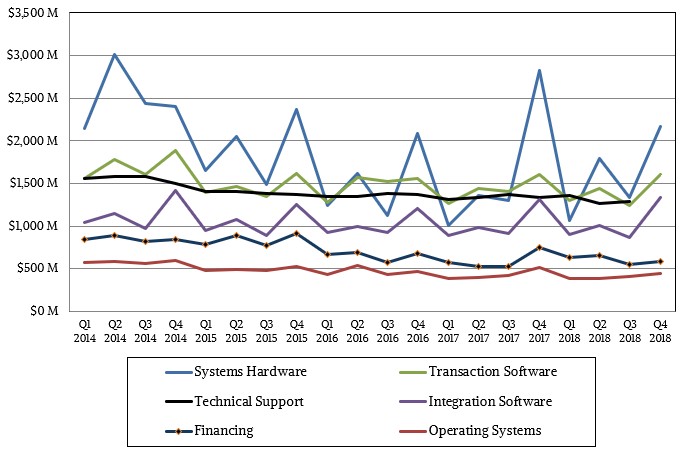

IBM has many different revenue categories, and this chart shows the ebb and flow of these divisions, as reported, over the past four years:

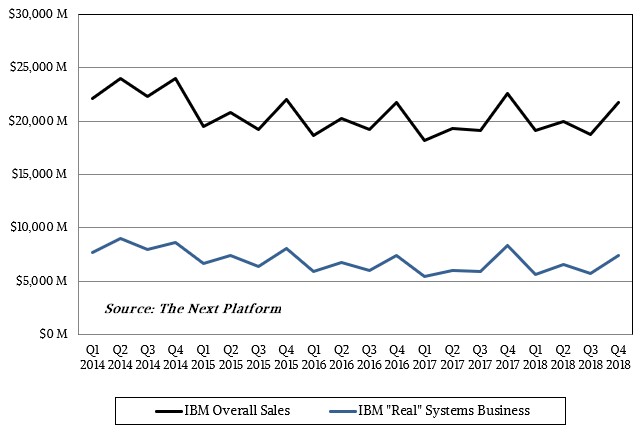

The software and support revenues are pretty steady, and you an see the spikes driven by the System z mainframe and Power Systems cycles in the systems hardware line in blue. There are a bunch of things that IBM sells that have nothing to do with its underlying systems business – the IBM Cloud public cloud is, for instance, largely built from Intel Xeon servers made by Supermicro, and it sells software for, offers financing for, and provides outsourcing for many different platforms besides its own. To get a sense of that “real” underlying IBM systems business, we extract what we think is a representative portion of technical support, financing, transaction software, integration software, and operating systems software that is actually running on the System z and Power System iron that IBM sells. If you do that, this is what that real systems business looks like over time compared to the overall revenues for the company:

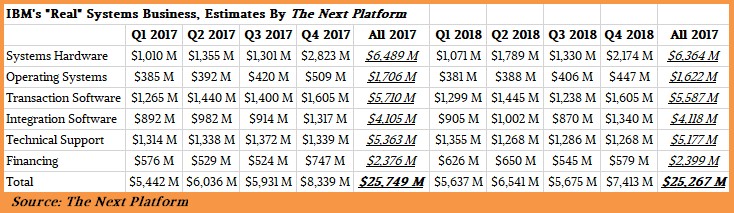

The fact that they track each other so faithfully is that our model has consistent ratios across the years. This is not meant to be precise – we have no idea how accurate our model is – but illustrative. The number wiggles around depending on the revenue streams, but generally speaking, the underlying “real” IBM systems business represents somewhere between 30 percent and 35 percent of its overall revenues. We reckon that for all of 2018, this true IBM systems business generated somewhere around $25.7 billion and fell about 2 percent. Here is a table showing the numbers:

IBM has always been obsessed by profit, mainly because its monopoly on mainframes in the 1960s and 1970s and its competitive position in midrange systems in the 1980s and 1990s gave it the kinds of profits that no other manufacturer in the history of history has been able to match. IBM was generating the kind of cash that Google and Facebook do today, and making bigger bets on technology, too.

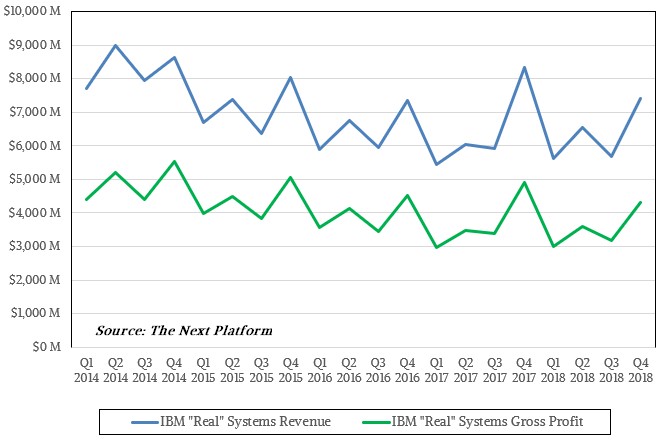

In any event, we estimate that IBM’s gross profits in that real systems business run somewhere between 55 percent to 60 percent of revenues, which is ten points better than Intel is doing with the official Data Center Group and even more better than it is doing with its own “real” datacenter business, which we estimate as well. Intel has just reporting its numbers , and we see what is up here.

The main thing about Big Blue is that it is riding its System z and Power cycles, and seems content enough in the results to keep investing. Which is good for customers using these platforms, and good for the competitive pressure it brings against Intel’s hegemony in the datacenter.

Good read. IBM also did something very interesting by incorporating nVidia GPUs in their “supercomputer”. The GPU wave is big and getting bigger and they teamed up with the category pacesetter.