It is almost a foregone conclusion that when it comes to infrastructure, the industry will follow the lead of the big hyperscalers and cloud builders, building a foundation of standardized hardware for serving, storing, and switching and implementing as much functionality and intelligence as possible in the software on top of that to allow it to scale up and have costs come down as it does.

The reason this works is that these companies have complete control of their environments, from the processors and memory in the supply chain to the Linux kernel and software stack maintained by hundreds to thousands of developers. This task, as we have pointed out, is made much easier by the fact that what these companies are scaling up are buy a few handfuls of applications.

Enterprises, by contrast, do not have these resources and this degree of control over their environments, and they have to rely on others to bring the software to market and support it for them. And not every application is going to be at a very high scale, so the compute and storage have to scale down as well as out. This is precisely what storage startup Excelero wants to do with flash storage.

Forget disks. These are for companies that need to store exabytes of data. If you only need to store terabytes to petabytes, a compelling argument can be made for going all flash, and the NVMesh software that Excelero has created makes it relatively easy to create a pool of flash that is perhaps a better server-SAN hybrid than the other commercial products out there – particularly when it comes to latency and scale. And as the company’s product name suggests, NVM-Express is at the heart of the architecture of its clustered flash storage.

“At the end of the day, we are an arms dealer, and we want enterprises to be able to deploy the same kind of weaponry as the hyperscalers,” Josh Goldenhar, vice president of products at Excelero, tells The Next Platform with a laugh.

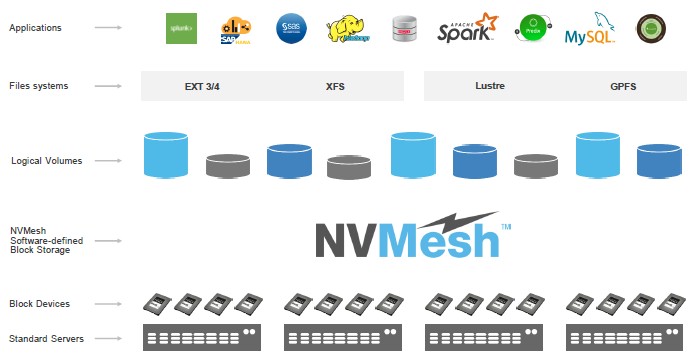

In a nutshell, what Exelero’s NVMesh software does is turn flash-infused servers into a storage cluster that supports block access protocols. Excelero wants to make use of all of the performance and capacity that is inherent in NVM-Express flash drives without trapping the gigabytes and I/O operations per second inside of a single server node, which is often what happens in the enterprise. NVMesh is a bit like the ReFlex research storage that we discussed earlier this month in that it wants to make a pool of flash external from servers look local to servers and nearly as fast.

Here’s the argument. By the end of this year, vendors will be delivering flash SSDs in the 2.5-inch U.2 form factor that weigh in at 16 TB and 32 TB, so capacity is not going to be an issue. These flash drives are getting so large that even with a PCI-Express 3.0 x4 interface, you will not even be able to come close in terms of pushing the limits on their endurance as measured in drive writes per day. So what will happen is that there will be middle of the road, mixed use NVM-Express flash drives, some being optimized for read (with maybe only 10 percent write ratings). Cutting to the chase scene, fat flash drives supporting NVM-Express with very high performance are going to be coming to market, and even now, the circuits to support NVM-Express only add somewhere between 7 percent and 15 percent to the cost, according to Goldenhar. As an example, the new SkyHawk NVM-Express drives have a 15 percent premium over regular SATA drives using the same flash, and they deliver around 3X the IOPS.

“We are big believers that by the end of the year, the industry will achieve price parity between NVM-Express and SATA flash drives, and in a very aggressive example, Intel’s P3608 NVM-Express flash drive costs 1 cent per GB less than the equivalent SATA drive,” says Goldenhar. “What I am trying to dispel is the notion that NVM-Express is more expensive, and that with the capacities coming down the pike, it won’t just be a performance story. That means NVM-Express won’t just be Tier 0 storage, but will move out to Tier 1 and, in some large datacenters like those run by the hyperscalers it will be the archive layer, too, because they will make up the cost difference with disks in efficiencies in power usage and space. We are not bold enough to say that NVM-Express flash will be cheaper than spinning rust, but it will be finally approaching it when you take into account total cost of ownership.”

So with NVM-Express being essentially free, and with the NVM-Express protocol extensible over fabrics to scale out storage, if customers have hundreds of terabytes to petabytes of flash storage all compressed into a relatively small form factor, as will be possible, this by default means in most cases that this will be a shared storage device. No single server, no single enterprise application, can make use of that capacity and certainly not that IOPS.

Excelero was founded back in 2014 in Tel Aviv, Israel, and now has its headquarters in San Jose. Lior Gal, who headed up sales at DataDirect Networks for its content and media business for many years, is a company co-founder and its CEO. Yaniv Romem, who among other things was vice president of research and development of server hypervisor maker ScaleMP, is the CTO at Excelero and Ofer Oshri, who was also a core team leader at ScaleMP, has joined as vice president of research and development. Omri Mann, chief scientist, also did a stint at ScaleMP. Battery Ventures asked David Flynn, who was a co-founder of flash pioneer Fusion-io, to do the due diligence with them on its investment in Excelero, and Flynn decided to kick in some of his own money to help get it going. To date, Excelero has raised $17.5 million in two rounds of funding.

NASA Ames is Exelero’s first paying customer (just like at DataDirect Networks decades ago), and the company also counts the PayPal payment service that was one part of online auctioneer eBay, media streaming service Hulu, and the Predix data analytics service from GE as customers, and there are, as usual, a whole bunch of proofs of concepts and early adopters who don’t want to let the cat out of the bag that they are using Exelero’s NVMesh software. Dell and Hewlett Packard Enterprises have been both reselling the software and it wasn’t even out of stealth mode yet. The 1.0 released NVMesh came out in July 2016 with limited availability, and 1.1 was released in February of this year.

The key to the NVMesh software is that it allows the pooling of NVM-Express flash and the accessing of those drives remotely with only an additional 5 microseconds of overhead to the latency compared to whatever the latency would be accessing it locally in a server or JBOF device. Generally, the latest generations of flash drives are about 20 microseconds for writes and 80 microseconds for reads, so add 5 microseconds to that to get a sense.

Excelero has demonstrated nearly 5 million random 4 KB reads on a 2U server with 24 flash drives with under 200 microseconds of average response time at a cost of around $13,000 for the hardware. (It won’t provide specifics on the hardware because it does not endorse any specific components or system suppliers.) By the way, with four high-end NVM-Express flash drives in such a box, at 3 GB/sec per drive you would completely saturate a single PCI-Express x16 slot with a 100 Gb/sec Ethernet or InfiniBand adapter. Adding more drives will give you more capacity, but not more performance – unless you add more network.

NVMesh pools the flash and creates a single logical drive and then carves them up into volumes of any size that can grow individually as workloads demand. And you can choose whether the volumes are concatenated, striped, striped and mirrored depending on the level of protection you want on the data in them. Excelero is not providing pricing on its software, but says a combination of generic X86 hardware with flash plus its NVMesh server-SAN overlay will be cost competitive with various enterprise-grade all-flash arrays, even reckoned with usable capacity, but it will offer somewhere on the order of 20X to 30X the performance.

The NVMesh software does require Remote Direct Memory Access (RDMA) of some sort be available on the network interface cards and switches, and it can be either the native InfiniBand or RDMA over Converged Ethernet (RoCE) variant. (NASA Ames uses InfiniBand with its NVMesh implementation, and all of the other customers to date are using RoCE.) Data Center Bridging (DCB) needs to be enabled, and NVMesh software also takes advantage of SR-IOV virtualization on server nodes. You have to pick the bandwidth of the network to meet the requirements of the workload, of course, but it will work with anything running from 10 Gb/sec to 100 Gb/sec, says Goldenhar. The clustering for the server nodes is done through the NVM-Express for Fabrics (NVMf) protocol, and Excelero has cooked up its own, patented Remote Direct Drive Access (RDDA) protocol to allow for flash drive to flash drive data transfers over the network without invoking the CPU networking stack, similar to what is done with main memory using RDMA in server clusters. The server nodes can be equipped with a low-bin Xeon processor, perhaps costing $300 to $450 per socket, says Goldenhar, because of that RDDA.

Excelero has tested NVMesh running on up to 60 flash drives per server and on up to 128 nodes within a cluster of servers using the 1.1 release of the software. A subsequent release, due in about two months, will span across tens of thousands of servers, if need be. That is a lot of scale, indeed. And we will believe it when we see it. . . .

The NVMesh software creates a pool of block storage, but the vast majority of customers are putting a file system of some type on top of it. Some are using multiple local file systems in top of NVMesh, such as XFS or ext4, NASA is using cXFS from SGI, and HPC customers tend to use GPFS or Lustre as you would expect. And Excelero has tested the Minio object storage stack on top of NVMesh, too.

One last thing. The NVMesh software is not restricted to any particular storage format – it can do SSDs, cards, or M.2 and U.2 hybrids so long as they support NVM-Express. Moreover, when other non-volatile media come to market, such as the Optane SSDs and the Optane M.2 sticks based on 3D XPoint from Intel, these will automatically be supported as a storage device in an NVMesh storage cluster.

Be the first to comment